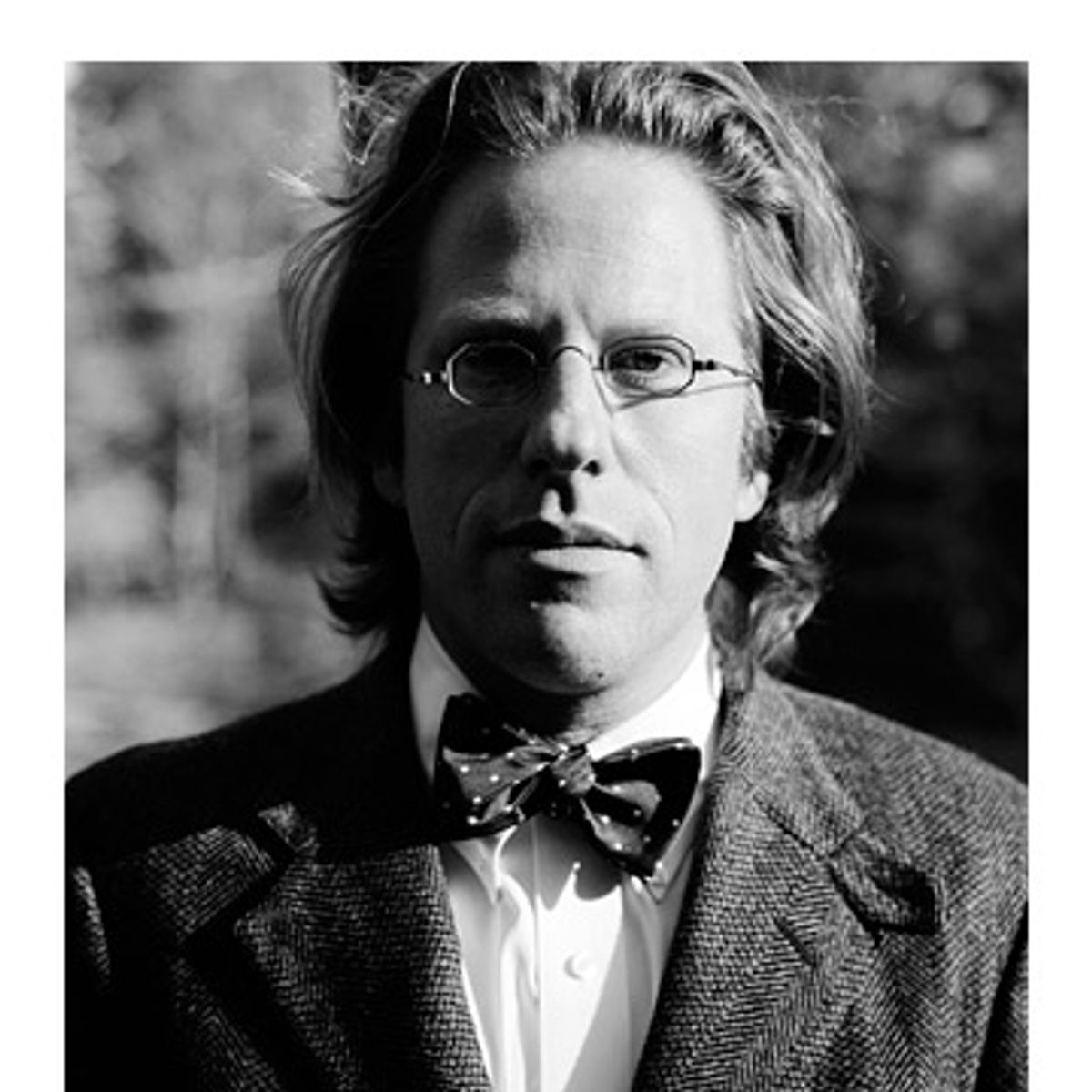

I don't know what's gotten into Jonathon Keats, 37, the San Francisco writer, Salon contributor, Bret Easton Ellis booster and conceptual artist, who once sat in an art gallery next to a naked woman, silently pondered, and then offered his thoughts for sale to bewildered art patrons. But whatever inspired this most cerebral artist to pen the warm and humane "The Book of the Unknown," certain to be one of the most original novels released this year, that should be conjured and sold in art galleries.

"The Book of the Unknown" is a collection of pre-modern tales -- picture "The Princess Bride" without the gloss -- that do an imaginative number on Judaism. They read as if a mischievous and slightly mad young scholar took up a secret residence in an ancient library and composed his own samizdat version of sacred Jewish texts. In fact, says Keats, "I wrote a number of them at the MacDowell Colony, where I had my own wood-burning oven. Every evening I would smoke myself out and in my delirium the tales would come. I mean, who doesn't like hallucination?"

Each tale follows a humble outcast. They include an idiot fisherman, a clumsy trapeze artist and a hapless gambler, who, unknown to themselves, act as saints, the fabled Lamedh-Vov from the Talmud, and ultimately show their fellow townsfolk "how to live." In one of the 12 tales, a saturnine thief, newly in love, stands in the dark and seems to see for the first time: "Desire burned in everything, sometimes less, sometimes more, kindled by the beholder. But while children could perceive that flame plainly, adults felt it only indirectly, as the heat of envy."

The following is drawn from an onstage interview I conducted with Keats inside a cavernous landmark building in downtown Berkeley, Calif., future home of the Judah L. Magnes Museum, which sponsored the talk. We spoke on the top floor, which features Keats' latest public artwork: stained-glass windows patterned as cosmic microwave background radiation, the so-called space between the stars in the universe. "The Atheon," as Keats calls it, is a "secular temple devoted to scientific worship." I was tempted to ask about the Atheon because I know Keats intends it to stir up arguments about science and religion, but I held back because I didn't want to get him started down the wrong path. We were here to talk about "The Book of the Unknown."

This is an amazing turn for you, Jonathon. These are simple and wonderful and magical stories -- not things you would associate with a conceptual artist who sells real estate in the 11th dimension, as string theory would have it, or who plays recorded religious prayers to fruit flies, and who …

You mean my attempt to genetically engineer God? Actually, that was part of a larger project, a sort of thought experiment undertaken in a laboratory. I was trying to discover God's place on the phylogenetic tree, but I was unable to obtain God's DNA, so genetic engineering seemed like the most practical approach to the problem. I worked with geneticists at U.C. Berkeley. In scientific terms, the basis was a process called continuous in vitro evolution, which has been used successfully to genetically engineer bacteria so that they'll consume oil spills. The underlying idea is to hijack the process of natural selection by ...

Keep it short, would you? We're supposed to be talking about your new book.

Well, briefly, given that people pray to God, I figured maybe there's a way in which God metabolizes worship. Playing prayers to various species as they evolved over many generations, I could see which ones thrived more than others. The species genetically closest to God would require the least mutation to exploit worship.

I see. Anyway, in "The Book of the Unknown," the contemporary fictional scholar -- very Nabokov of you -- writes in the forward that each of the tales follows one of the Lamedh-Vov, the saints who don't know they're saints. You were drawing from the Talmud, right?

Yes, I plagiarized everything I could misremember, and a lot of what I misremembered was Jewish legend. The Lamedh-Vov are the 36 righteous, according to Hebraic lore. They are anonymous, unknown to everyone, even to themselves. Were one to know that he or she was amongst the 36, he or she would no longer be one.

Why not?

Traditionally, the Lamedh-Vov are the least expected people: the chimney sweep or the water carrier, rather than religious and political leaders. So that's the simplest answer. Another way of thinking about it is in terms of a line from Talmud that I use as my epigraph: "Despise no man and deem nothing impossible, for every man has his hour and every thing its place." That passage is not specifically about the Lamedh-Vov. But I think it's crucial in terms of suggesting the way in which there are limitations to our ethics. Where saints typically stand as moral guides in the absolute sense, these 36 serve as a check on our judgment. Also, these stories were written during the Bush administration, when self-righteous judgment was rampant beyond anything I'd ever experienced in my 37 years.

In one of your stories, "Yod the Inhuman," one of the saints is a golem. She is made out of mud by a Jewish scholar, who teaches her to experience pain and pleasure, and then he has sex with her. Later she becomes a whore to the whole town. I take it none of the original Lamedh-Vov from the Talmud were golems.

Well, there's no way for us to know, given their anonymity, but I will say that even to make a golem female is pretty uncommon. As far as I'm aware, all the golems in Jewish legend were burly men. They were obedient brutes, useful in a pogrom, but hardly models of righteousness.

I'm not a Jewish scholar, but "Yod the Inhuman" sounds pretty blasphemous to me. Does it worry you that you may be blaspheming Jewish tradition and sacred texts?

If I'm blaspheming, it means I'm doing my job as a writer, and also, I believe, being true to the deepest value in Judaism, which is the value of questioning. Some people won't agree with me, and not only the Hasids who commit the ultimate sin of religious fundamentalism. My ancestors founded one of the first Orthodox shuls in New Jersey, and I'm sure that many of these stories would mortify them. They probably wouldn’t like Yod's aggressive sexuality, and would be even more upset that my Lamedh-Vov include a gambler, a thief, a murderer and -- God forbid -- a false Messiah.

But to write about each of these was a test for me, to see whether I could let go of conventional judgment, to broaden my understanding of evil and goodness. So we're back to the notion of thought experiments: Is there a possible world in which a murderer might serve some noble purpose? Well what if, once upon a time, long ago and far away, there were a city so remote that it was overlooked by the angel of death?

Have you been a good Jew in your own life?

I butchered the Hebrew language at my bar mitzvah. And, when it comes to liturgy, I'm emphatically agnostic. But I think that at some deep level my Judaism has informed the way I live my life: the sorts of questions that I ask, and the sort of emphasis that I put on questions in their own right.

Your first novel, "The Pathology of Lies," was about a female magazine editor who kills her boss and sends his body parts to the magazine's subscriber list. Are you doing penance with "The Book of the Unknown"?

Probably not in the way that you mean. "The Pathology of Lies" was written in the spirit of contemporary literary fiction. It was satirical, and fundamentally modernist in the sense of being fractured, a narrative structured like life rather than with the internal coherence of an old-fashioned tale. If I'm doing penance with "The Book of the Unknown," it's by committing the literary sacrilege of breaking with modernism.

Why would you want to do that?

There's nothing harmful about modernism per se, but it is rather retrograde. Life is fractured and confused, there's no denying that, yet in their efforts to mimic those qualities, the modernists and their postmodernist imitators abandoned the very reason for telling stories, which is that stories reconceive life. Myths and folk tales and fables are alternate realities, simplified and stripped of current events, microcosms that we can enter into completely while recognizing their artifice. They are akin to the philosophical thought experiments that motivate my conceptual art. The modernist assumption is that people used to be too "primitive" to realize that their tales were unrealistic. In truth, the pre-moderns were ahead of us in that they had greater force of imagination.

Well, I don't mean to criticize your artwork, Jonathon, but the stories feel so much warmer. They're alive with love and jealousy and loss and reconciliation. Are you showing us a new side of yourself?

It's a fair question, and if you see me differently through this new work, I'm not going to contradict you. But speaking from my own perspective, the underlying motivation -- curiosity about the world in all its peculiarity -- is the same in both cases, as is the fabulistic what-if approach to life. If the feel of this fiction is different, it's because storytelling is a different mode of inquiry, and I think that one of the reasons why I value writing and art equally is that each has its own inherent qualities. Taken together, they allow me to reflect on the world in stereo.

Would you say you're a spiritual person?

If you can define spirituality for me, I might be able to tell you. Probably my answer would be yes and no. I don't buy into crystals and gurus, or practice Bikram yoga, but I do write stories. And that's a spiritual pursuit in that it demands a suspension of disbelief; it demands a total commitment to figures who are, in literal terms, fictional. Yet I believe in them completely, and I believe in them because I have to believe in them, not because I want to do so. So I think that in that sense, yes, I must be spiritual. Also, I'm rather superstitious. A hat on a bed really disturbs me. Maybe imagining the fate of the hat's owner is what made me into a writer.

Don't you think reading is also an act of faith?

Absolutely, and especially when reading fiction. In recent years, fiction has been largely abandoned in favor of nonfiction, which of course is half made-up in its own right but carries the imprimatur of truth so that the reader need not apply any imagination. The decline of fiction has weakened our faith -- our ability to suspend disbelief -- and has created an imaginative vacuum exploited by religious dogma and intolerance. Maybe that's what motivates me to write tales as simply as I can, so that they can be read by anyone, anywhere, even aloud. This is one of the unrecognized virtues of short stories, and perhaps a sign of the novel's obsolescence. Fiction ought to be an everyday encounter, not because it's informative or useful, but because it isn't.

-------------------------

Jonathon Keats reads from "The Book of the Unknown" March 11, Strand Book Store, New York; March 12, Brookline Booksmith, Boston. Read the tale "Alef the Idiot" here.

Shares