In popular culture, female friendships often fall into two extreme camps: There are the giggling, cocktail-swilling BFFs of "Sex and the City" and the backstabbing bitches of "Gossip Girl" and "The Hills." In real life, female friendship is a much trickier beast, filled with slippery contradiction and embarrassed envy, territory that Lucinda Rosenfeld stakes out in her new comic novel, "I'm So Happy for You."

The book tracks the relationship between Wendy and Daphne, two college friends stumbling through their 30s in New York. But when Daphne — once the lonelyheart prone to making melodramatic late-night phone calls and falling for the wrong men — finds sudden bliss, Wendy finds herself mired in the kind of jealousy and self-pity that can get you blacklisted from the ya-ya sisterhood of the traveling pants.

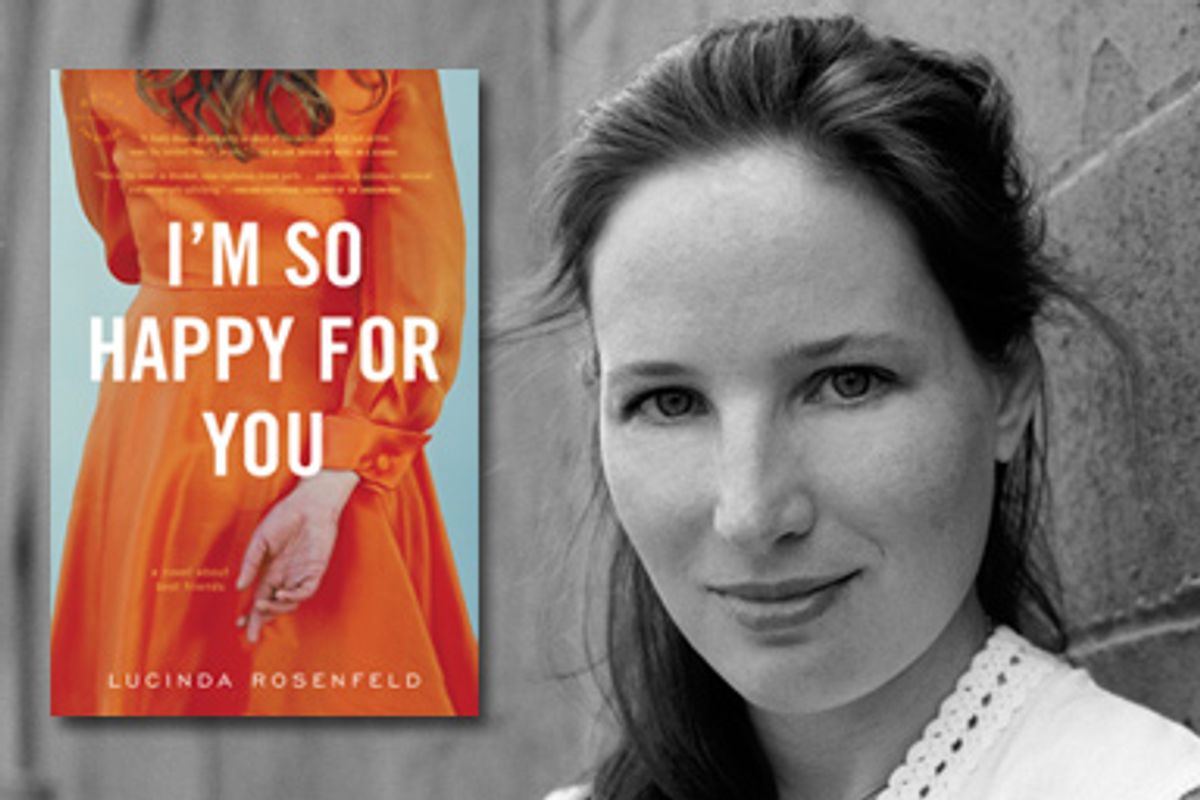

Like her acclaimed first novel, "What She Saw in Roger Mancusco," Lucinda Rosenfeld mines feminine self-sabotage and neuroses for laughs. She also turns a satiric eye toward such fertile territory as motherhood, childbirth and status-seeking among urban elites. Katharine Mieszkowski spoke with Rosenfeld, who lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two daughters, about how the female dynamic fascinated her, why self-deprecation might be unique among American women, and why she wanted to plant a stiletto in the back of "Sex and the City" clichés. —Sarah Hepola

So why did you want to write a novel about the souring of a friendship between two women?

Obviously, novels thrive on conflict, and when two people are happy, whether it’s in a marriage or a friendship, there’s no story. But I also was interested in the way that sparring female friendships, which people usually associate with grade school, seem to continue into women’s adulthood and middle age, or maybe to the end. I just thought it was a somewhat unexplored subject.

At the beginning of the novel, Wendy is used to propping up her friend, who is always in disarray and is having an affair with a married man. And suddenly that shifts, when Daphne's circumstances change. And this throws the friendship into turmoil.

Friendships can be odd and complicated — people can thrive on other people’s dysfunction. Everything goes back to the question of envy, which is really the great theme of the book. The question of, Are we always really happy for our friends? and, Is it possible that Wendy is getting a lot out of Daphne’s misery, more than she’s even willing to admit?

Right, it makes her life seem better?

It makes her feel better, and it makes her feel useful. She thrives, at the beginning of the book, on being the stable one. She finds Daphne annoying, but she also derives a certain amount of self-esteem from watching her formerly fabulous friend flailing a bit.

And she gets to play the great nurturer and giver of comfort.

She gets to play the best-friend role, which makes her feel important. It makes her feel needed. It allows her to compare her own life, which she’s not particularly happy with, in a favorable way. She’s looking for reasons to feel better about her own marriage, and when she compares her romantic life with Daphne’s, it comes out looking really good — in the beginning of the book, that is. Which is why, when Daphne hooks up with her fabulous husband-to-be, Wendy is suddenly so much more critical of Adam, her own husband.

I’m not saying all women are like this. Some people have asked me, “Why did you write about such a nasty portion of female friendship?” Well, I think there are plenty of friendships that don’t thrive on envy and schadenfreude, but there are also friendships that do.

I thought one thing that’s interesting about Wendy’s envy is she’s so afraid of it. She’s so horrified that she’s having these emotions. A lot of the conflict of the book seems to be within Wendy about how she has to perform this role of the good friend when that’s not how she feels.

I’m glad you’re saying that, because some people have read Wendy as unabashedly bitchy and envious. But I tried to put forward a character who was fighting her own feelings too, who actually wants to be happy for her friend but is finding it extremely difficult. Which I think is more real to life. I think that most of us do want, in theory, the best for our friends, but we find it difficult to be happy for people when things happen for them that haven’t happened to us already.

Did you feel like the jealousy itself was the great taboo, not only within this friendship but then also within the circle of friends — that the women couldn’t really admit it to each other?

It is a forbidden emotion in some way, especially when it comes to talking about money. Money is the one area, people agree, it’s embarrassing to talk about. But I think envy is an embarrassing emotion on all fronts, and we do try to disguise it.

In recent years, we've had this "Sex and the City" ethos — friends always come through, and you still have your friends even when love fails. But I think friendships are just as complicated as marriages. And in some way marriages are more straightforward, because you’re allowed to talk about upsetting emotions within a marriage. But with friends there’s this embarrassment level about envy. No one’s allowed to admit to each other that they’re envious.

I don’t know if you’ve ever told your friends you’re envious, but I don’t think I ever have. It would just be so mortifying.

At the time though, it seems very important to Wendy that she is seen as Daphne’s closest friend, there’s sort of this thrill she gets from knowing information about Daphne’s latest crisis, or latest success, first, and then sharing it with the group of friends. This power of being the best friend is still very important.

I felt excited writing about that because I felt like it was an area I hadn’t ever seen explored, which is the weird power struggle in a group of women to claim friends as — I don’t know what the word is, but the power struggle to be the most important one to someone else, to be someone else’s best friend, and to be seen as being the gateway to that person, so when there is a crisis, the gateway person is called upon to explain what’s going on.

It comes across as a delicious power in having information, and then disseminating it to various other people.

Yes. And the way in which we sometimes say things about our friends to other friends, not just to gossip, but to prove how close we are to someone else as a status thing. I’m really fascinated by that subject, actually. You think that jockeying would end in high school but, I don’t know what your peer circle’s like — this is going back to why I started the book — but the older I get, this stuff seems to actually increase in interest. The power struggle within a larger clique of who is no longer getting along with who and who now claims more of the "best friend" title. It might not be spelled out as "best friend" — that sounds like a juvenile phrase — but this stuff seems to continue.

But then there’s this other currency among the larger group of friends, in which disclosing your own vulnerability is important. If you don’t engage in that, then you’re an ice queen, like the character Paige, and no one can relate to you.

Paige is a little bit of a stock villain. I’m not sure how many Paiges really exist. I guess there are a few. But the self-deprecation is another strain I’ve picked up over the years in women. I think it’s particularly American, because I have a few German friends and they never do stuff like that. Maybe it’s competitive too: It’s like simultaneously putting yourself down and propping yourself up. Status jockeying and also self-deprecation jockeying: Whose life is worse? It starts in high school or grade school. Who did worst in the test? “No, I failed,” “No, I really failed that test.” “I’m sure you did better than I did.” But the subtle ways in which we take each other down and build ourselves up.

I wrote a book that's a quite biting picture of friendship. I wouldn't be writing this if I weren't fascinated by friendships and also with how wonderful they can be. I think that they fill a very large role in adult life, especially today, as we don't live so close to our families necessarily, don't necessarily belong to churches, or temples or whatever. But in any community there's going to be strife. This is my attempt to pull the lid on the cliché of sisterhood.

I also thought the book was about a transition from the 20s, where everyone seems the same in terms of their prospects in life, and then into the mid-30s, where the choices you've made are narrowing your prospects in terms of what you're going to do.

I'm a little obsessed with the money question. I grew up very modestly, but I was always surrounded by rich people because I ended up at a private high school. I don't have Wendy's background at all, and I'm not Wendy. But I go through life extremely aware of the differences.

I do think that money becomes a real sore point. There've been studies done about friends, and people basically can only be friends in life with people who are roughly in their socioeconomic bracket. It's very rare you would find a billionaire being friends with a lawyer. It's the same reason I guess celebrities hang out with each other. It's OK when they're billionaires, but if the guy next door to you makes more money, then that really hurts.

There's this whole social convention around the breakup of a romance, and how you're supposed to feel about it, and how you're supposed to behave. But there really isn't that for friendships. The breakup of a friendship is somehow more shocking.

Right. And I think that for women, some of these breakups can be absolutely devastating in the same way that a romance ending can be. I write a column about friendship for DoubleX, and I've covered some of this in there, but — I had a friend basically dump me in my 30s. And it was really devastating. I felt so hurt. And there aren't any established rituals around it.

There's something singularly upsetting when a friend blows you off or is angry at you. I don't know what it is in particular, but it can feel quite devastating when there's a nasty e-mail, and you can't just snap your fingers and make up in the same way that you can with a romantic partner, and just turn the fight into a smooch or something.

Do you have any theories about why it's been underexplored before? Why do you think there's not that much written about it?

I keep going back to "Sex and the City," and I think there were completely unrealistic pictures of friendship, but it brought to light the fact that in urban settings, in particular, friends have become de facto families. And so when you have de facto families you have fights and conflict and excitement in a way that you don't with friends you see three times a year. And also obviously people used to have kids younger, and children can make it more difficult to keep up these friendships. But obviously, the great plot of life is, there's war and there's love, and love is more dramatic than friendship. From a narrative point of view, friendship less lends itself to a novel than romance or war.

I find it just as dramatic though. That's the thing.

Shares