More than a decade ago, a 42-year-old man walked into the office of Susan Clancy, then a Harvard graduate student working with child abuse victims, and made a revelation that would help shift how she viewed her entire field. When he was 9 years old, the man said, a friend of the family had sexually molested him over a six-month period. The man kept the abuse a secret from his wife and family for more than 30 years and was struggling with feelings of shame and problems at work. But this wasn't nearly as surprising as what he revealed next: When the sexual abuse was happening, the man said, he wasn't even upset.

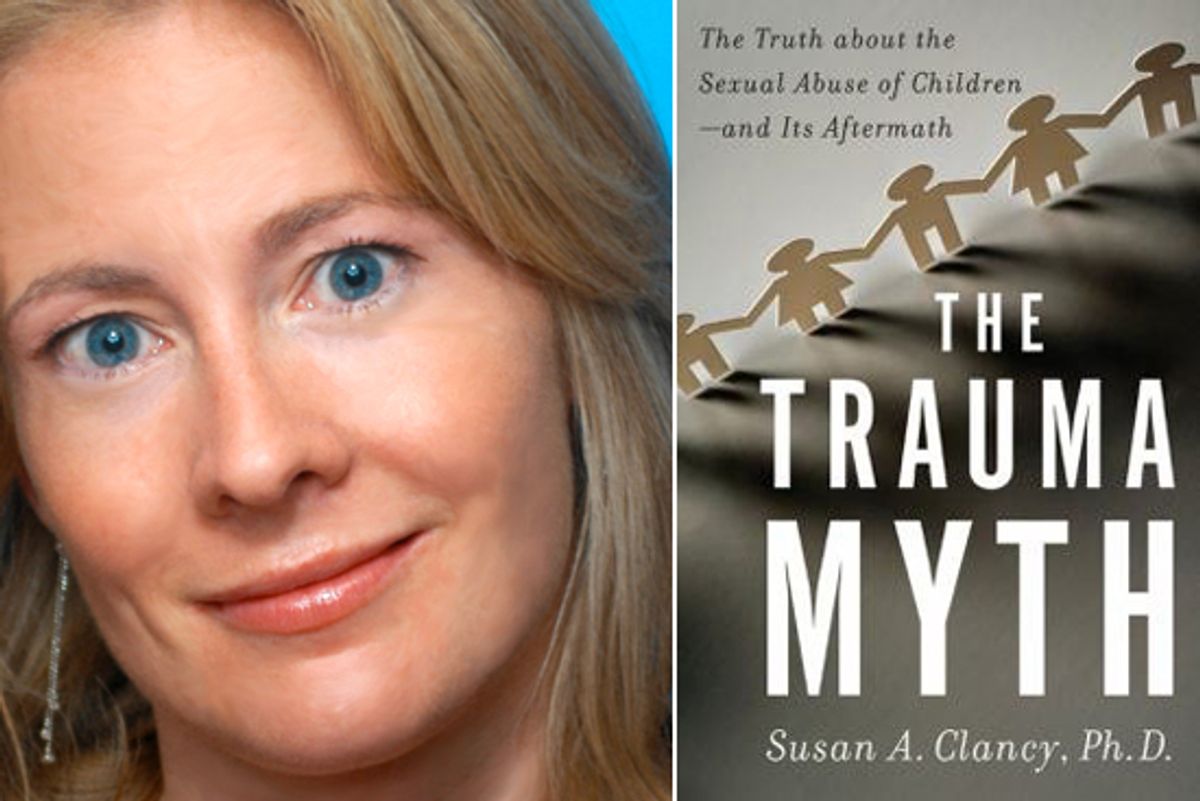

Clancy tells the story in her new book, "The Trauma Myth," not only to startle readers, but also to describe the extent to which she believes many people in the medical establishment have misrepresented the realities of child abuse. The book marks a controversial break with the current line on sexual abuse, but Clancy is no stranger to controversy. A former Harvard psychologist and the current research director at the Harvard-affiliated Center for Women’s Advancement, Development and Leadership in Nicaragua, Clancy's previous book, "Abducted," was a much-debated attack on repressed memory. In a 2003 New York Times magazine profile about her, well-known trauma therapist Daniel Brown lashed out at Clancy's "political agenda," and Clancy's hate mail has included accusations of cheering on child molesters and even abusing children herself.

Despite its provocative thesis, however, "The Trauma Myth" is a nuanced and muscular work that takes a surprisingly straightforward approach to a tough subject matter. Salon spoke to Clancy over the phone and via e-mail from Nicaragua about our society's misconceptions about child abuse, the media's dangerous portrayals of molestation, and why the "trauma myth" helped Roman Polanski sway public opinion.

What do you mean by the "trauma myth"?

The title refers to the fact that although sexual abuse is usually portrayed by professionals and the media as a traumatic experience for the victims when it happens — meaning frightening, overwhelming, painful — it rarely is. Most victims do not understand they are being victimized, because they are too young to understand sex, the perpetrators are almost always people they know and trust, and violence or penetration rarely occurs. "Confusion" is the most frequently reported word when victims are asked to describe what the experience was like. Confusion is a far cry from trauma.

At what point did you conclude that something was wrong with the way we think about child sexual abuse?

What was shocking to me when I started my research was the number of people who were victims of sexual abuse and hadn't told anybody before. All day long I would interview people — my whole life was surrounded by victims — and I was hearing the same thing: This is the first time I've talked about it. I was thinking, How is this possible? We've been talking about sexual abuse and trauma on the news 24/7. You get all these people who are keeping it a secret because they're ashamed — because what happened to them is not what is portrayed in the media or psychological and medical circles.

Why is this distinction important?

If you really want to help people, if you're really trying to prevent and treat a social problem, you have to describe the problem truthfully. For 30 years we've been working on preventing sexual abuse. But we've skirted around what sexual abuse really is. The kids don't know what's going on, and they often enjoy it. They're not going to resist.

If this is true, why hasn't it been put forward before?

In the 1950s and 1960s, psychiatrists were very open and honest about sexual abuse, but there was also that tendency to think it was the child's fault. Feminists were naturally infuriated, because it's not the children's fault! But the way they got attention to it was to portray the sexual abuse in a way that would shock people. They did that by comparing it to a rape. Before that, the reaction from the medical and psych communities was, "This is not something we really care about." It wasn't until feminists and child-protection advocates misportrayed it that we were able to arouse massive medical and scientific attention to the topic.

How does what you call the trauma myth hurt people who were actual victims of sexual assault?

Ninety-five percent of sexual abuse victims never seek treatment because of what they falsely assume and fear about sexual abuse. Many of them do not even think they were sexually abused. This is a huge problem. You have people who call me and say, "My uncle attempted sexual penetration when I was a child, but I'm not sure if I qualify as a sexual abuse victim." I say, "How in God's name do you not think you're a sexual abuse victim?" It's because in most cases of sexual abuse, it was not traumatic when it happened.

It's a very fine line between what you're saying and saying that children aren't hurt by sexual abuse.

I will never say that. I could not be more clear. This is an atrocious, disgusting crime. People have a tendency to assume I'm saying it's not a big deal or it's the child's fault. Most people don't want to think too hard or thoroughly about these things.

One could argue that your claims could encourage child abusers — or convince them that what they're doing isn't wrong. How do you respond to that?

Forcefully! As I hope to have made clear in the book, sexual abuse is never OK. No matter what the circumstances are, or how it impacts the victims, sexual abuse is an atrocious, despicable crime. Just because it rarely physically or psychologically damages the child does not mean it is OK. Harmfulness is not the same thing as wrongfulness. And why is it wrong? Because children are incapable of consent.

Children do not understand the meaning or significance of sexual behavior. Adults know this, and thus they are taking advantage of innocent children — using their knowledge to manipulate children into providing sexual pleasure. Sick.

You spoke to 200 people as part of your research at Harvard. Isn't that a small sample from which to draw these conclusions?

No, my sample is not small compared to most community samples used in social sciences research. Plus, my findings perfectly mirror the findings from national epidemiological studies that randomly sampled members of the U.S. population. This is significant. The main takeaway is that my findings were perfectly consistent with findings from the general population of sexual abuse victims.

Your previous book was a take-down of recovered memory. This book also takes a very negative view of recovered memory. Why are you so opposed to the idea of recovered memory?

Because it doesn't exist. There is not one single research study showing that people exposed to horrifying, overwhelming, painful events "repress them" and recover them later on. Rather, people exposed to horrifying events report that they often remember them all too well. Ask any child exposed to the recent earthquake in Haiti if they "repressed it." None will. True trauma will always be remembered. Richard J. McNally's "Remembering Trauma" is a comprehensive critique of repression. Repression is a psychiatric myth.

What therapists in the sexual abuse field refer to as repression is actually simple forgetting. Most children who get abused don't understand it at the time. Thus, it is not a significant experience when it happens — it's weird, perhaps — and so they forget it, like we forget so many aspects of childhood. Later on in life they may be asked by a therapist, "Were you sexually abused as a child?" and this question will cue a memory. When this happens it is not an example of a recovered memory. It is an example of normal forgetting and remembering.

The idea of repression ultimately hurts victims. It reinforces the notion that sexual abuse is and should be a traumatic experience when it happens — something done against the will of the victims. Since for most victims this is not the case, they end up feeling "alone," "isolated" and "ashamed."

You write that you've experienced quite a backlash from your work on child abuse when you were at Harvard. Was it really that bad?

It's bad enough I moved to Nicaragua. When I was at Harvard — the peak of my career, at the university you want to be, surrounded by all the people who were the titans in the field — there was just so much bullshit going on. People focused on a type of abuse that affects maybe 2 percent of the population, millions of dollars for funding that doesn't apply to most victims, bestselling books written by therapists misportraying sexual abuse. I would try to tell the truth. I would be attacked. Grad students wouldn't talk to me.

Professors would tell me to leave for other fields. I just felt disillusioned. I got this opportunity from the World Bank to do cross-cultural research on how sexual abuse is understood in Latin America. I came down to Central America, and I've stayed.

To what extent have movies and TV been responsible for perpetuating what you claim are false portrayals of child abuse?

I think it does a disservice to victims. There were a number of movies in the last few years where people were so traumatized by sexual abuse that they needed hypnosis to bring back the memory. In 5 percent of cases it is awful, and medical attention is required. For 95 percent of victims, that's not what happens.

Look at "Mystic River." In that movie child sex abuse involves a faceless priest. The child is destroyed for life. There's a sadistic aspect to it that has nothing to do with what happens to most kids.

Do you think there's any movie or TV show that's done a good job of portraying sexual abuse?

There's a moment on HBO's "True Blood" in the first season, where Sookie Stackhouse is talking to Bill, her vampire lover, about what happened between her and her uncle, and I thought that was a very good depiction. She said it didn't ruin her life, but it's sad that something like that has to color her feelings about sex and intimacy as an adult. It wasn't out of control. They didn't make it sensational.

You argue that one of the reasons so many people misunderstand child sexual abuse is that it's often compared to rape. How do you feel about the term "statutory rape"?

It's outside my bailiwick to comment on legal terms, but in an ideal world I don't think that's the term we should use. I think there should be clear legal terms to differentiate sexual abuse that involves touching and no force, and sexual abuse that's penetrative, and sexual abuse that involves force and violence. You have to make it clear that in all cases it is a crime, but clumping all of them under one title — when they range from genital stroking to anal penetration — is a bad thing.

Do you think that Roman Polanski should be put in jail?

The Roman Polanski case is a clear case for sexual abuse. It's infuriating that people are losing the main point. He's a guy who had sex with a child. If she had been beaten or if she had been rushed to the hospital, it would have been an entirely different situation, but because she wasn't physically traumatized nobody cares. She was drugged, the poor thing. If he had slapped her around, if he had pushed her up against the wall, he would have been locked up. Ninety-five percent of children don't fight it because they don't understand what's happening and because when they tell the truth nobody cares.

How do you think we should change the way sexual abuse victims are treated?

I think practically, sexual abuse victims need to hear loud and clear that what happened to you is what happens to most people. It was wrong and not your fault, and you should report the crime, and the perpetrator should be punished. I don't think that sex abuse victims in most cases need years of therapy to get over the betrayal. What they need first and foremost is the straightforward truth: You are not alone, you have nothing to be ashamed of, it's his fault, and this is a crime.

There's something I would like to add. Despite all of this media and research attention on sexual abuse for the last 30 years, I still don't hear the answer to one question: What the fuck is wrong with all of these men? Sexual abuse is not women; it's men. Every once in a while a woman will sexually abuse, but in 95 percent of cases it's a man that is known to the child — a teacher, a friend, a family member. These are high-functioning people in society who are choosing to molest children. All this focus on the psychology of the victim is a way to sidestep this central question: What is going on in society that so many men are choosing to get off on small children? I can find almost no studies on the subject. People will go into jails and interview a perpetrator, but most of these people don't go to jail, and most of them aren't caught.

Shares