When I first met Piper Kerman in the mid-'90s, I knew her as the vivacious, whip-smart girlfriend of my friend Larry Smith. What I didn't know was that Piper had a secret.

A few years earlier, shortly after graduating from Smith, she had been involved with a woman who was a drug trafficker. For a few heady months, Piper traveled with her girlfriend on her dangerous business and had even, on one occasion, couriered money for her.

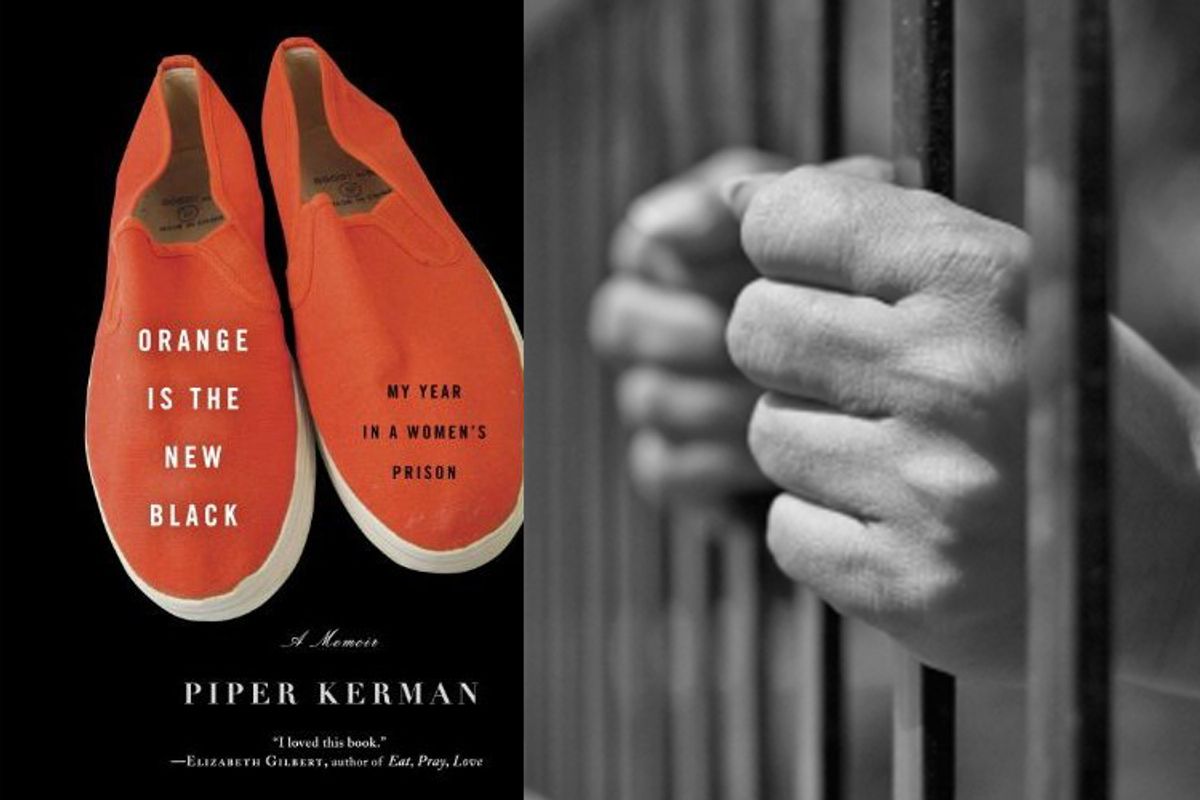

Eventually, however, the past caught up with Piper. For her youthful transgression, she was sent to federal prison in Danbury for a year. Now, five years after her release, she's written an honest, insightful and often very funny book about her experiences — the wryly titled "Orange Is the New Black."

A few days ago, far from the confines of correctional facility cuisine, we sat down together at New York's City Bakery to talk about her book and the truths and misconceptions about the American penal system.

Let's start with the obvious. How'd a nice girl like you get yourself in such a pickle in the first place? Did you ever think you'd wind up in jail?

I knew what we were doing was illegal. But the more you see people not getting caught, the less convinced you are it'll happen, whether it's Enron traders or street dealers. And the thing about young people is that your risk calculus is off-kilter. I was in denial about the relationship between my actions and what would happen to other people — whether it was people who were addicted to drugs or my own nearest and dearest. That's at the heart at any crime — your own indifference to the consequences.

When you finally got out, you could have put the whole episode behind you. Why did you decide to write about it?

There was no question that folks were interested in the story. When I came home, every person I knew or met said, "Tell me more." But my story relates to the story of millions and millions of Americans. There are two million people in jail right now, and seven million on probation and parole. Then there are their children, their parents and their community.

My experience was so different than what's typically depicted about prisons. I wanted to offer a more complete, complex picture. Most of the pop culture is about men. It's all about "Oz." There's the expectation that prison is full of irredeemably violent people. The prison I was in was full of ordinary moms and grandmas and young girls convicted of nonviolent crimes.

What surprised you most about prison?

I went in being warned not to make friends. Now I can't conceive how you could get through it without friends. You need other prisoners to get you toothpaste, to get you soap. There's this lag time between arriving in prison and getting those basics, so I had almost a month where I was completely reliant on other prisoners. And other prisoners were very generous and kind.

People think the prisoners are scary. What you're scared of is the guards and losing the tiny privileges you have. They can take away your visiting rights or your cubicle. They can go into your locker. You have your tiny world, and they can take that all away. The determination to hold on to your individuality and your community is very important.

What do you think needs to change about the way the penal system is currently run?

Low-level offenders make up a big portion of the prison offenders. In 1980 there were only 500,000 Americans in prison. Over the last 30 years, the government has being using prison to try to address problems of poverty. Plenty of rich people commit crimes, but most of the people in prison are poor. They come from the most fragile communities. Prison has not worked well as a solution to poverty.

But now because of the economy, states are being forced to figure out smarter ways of dealing with crime. If we shift resources toward probation and parole, it would be potentiality cost-effective. There are sanctions in the community that can happen. Michigan, for example, has reduced the number of people they're sending to prison and not seeing any increase in crime. California, meanwhile, is still spending $47,000 a year per prisoner.

But if you have young people in trouble and you succeed in getting them on the right path, that's not just humane, it also yields a big reward to our society as a whole. The system is a warehouse. And the biggest battle for prisoners is just to not to turn into a box on the shelf, and stay human.

Shares