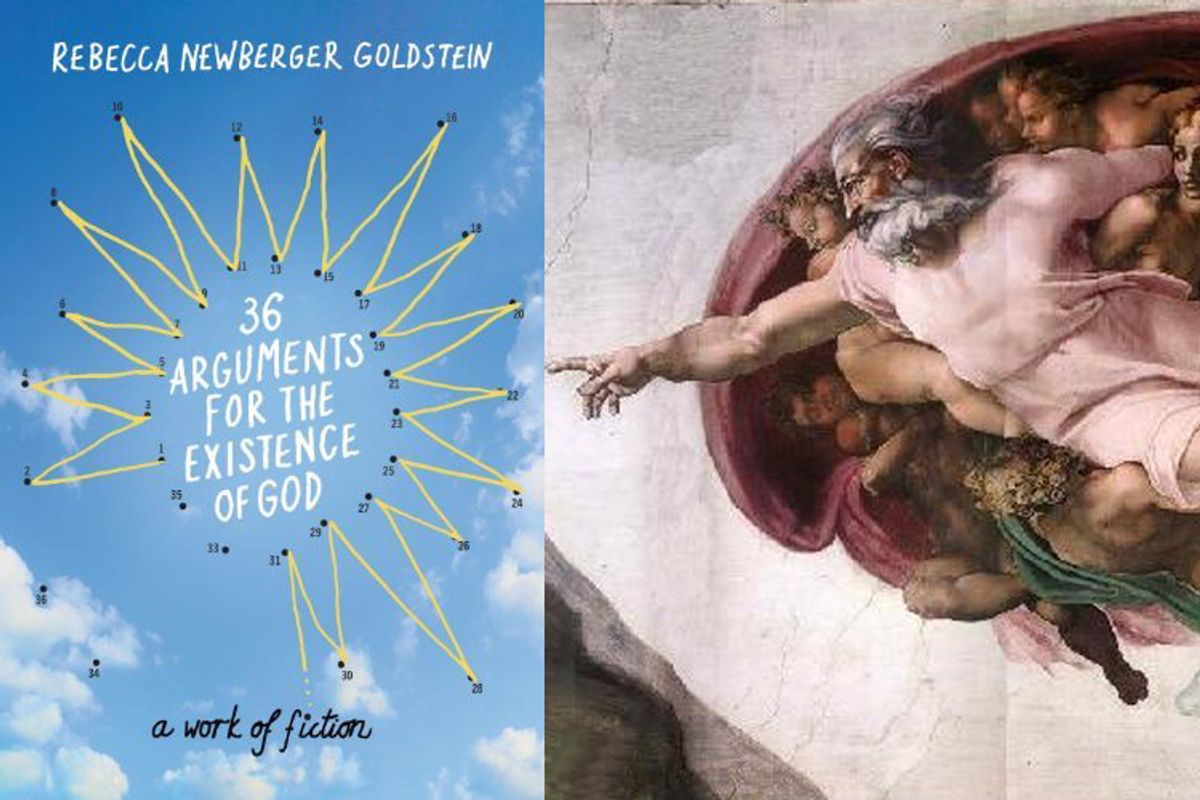

Humanity is an ape with its head full of stars, and the precarious intersection it occupies between the corporeal and the transcendent is one of literature's great subjects. Sometimes, an author approaches this incongruity as a tragedy; even the most exalted among us are creatures of the flesh and doomed to die. But satire works, too, as Rebecca Goldstein's new novel, "36 Arguments for the Existence of God," effervescently demonstrates.

The novel's protagonist, Cass Seltzer, dubbed "the atheist with a soul" by the press, is a psychology professor at a small Massachusetts college who is rocketed to the intellectual's version of fame after he publishes a surprise bestseller titled "The Varieties of Religious Illusion." He's been profiled in magazines and invited onto "The Daily Show." In the course of the day during which the novel takes place, he encounters an ex-girlfriend, moons over his current girlfriend, thrills to a job offer from Harvard and prepares to debate the proposition "God exists" with a suave, ruthless neoconservative theist before a standing-room-only crowd. Much of the novel, however, consists of Cass' reminiscences about the past couple of decades, years during which he made the unlikely journey from dutiful pre-med student to celebrity philosopher.

Goldstein herself is a professor of philosophy as well as the author of several novels and nonfiction books on Spinoza and the mathematician Kurt Godel. She's also married to the cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker ("The Language Instinct," "The Blank Slate"), which has surely given her a firsthand perspective on the experience of an academic popularizer. Cass, who specializes in "the psychology of religious conviction," feels no small chagrin in the knowledge that it's the appendix of his book, in which he lists and refutes the 36 arguments of the novel's title, that has gotten the most attention. In the knock-'em, sock-'em world of contemporary atheism debates, his more considered and nuanced work gets shoved aside as partisans avidly search for more ammo to use against the enemy.

"36 Arguments for the Existence of God" marks a turning point in academic satire, that small but addictive genre devoted to skewering the foibles of university mandarins. In the '80s and '90s, trendy post-structuralist theory was all the rage in the humanities, and the sanctity of objective knowledge itself was challenged by trickster savants spinning impenetrable and often perverse thickets of jargon. The best-known send-up of this period is a trio of novels by David Lodge, beginning with "Changing Places," but James Hynes ("Publish and Perish") and John L'Heureux ("The Handmaid of Desire") also delivered biting portraits of faculties riven by warring multiculturalists, deconstructionists and old-school dead-white-male buffs.

The stars on campuses now, however, are champions of empirical knowledge and Enlightenment thinking -- scientists, mathematicians and other critics of "those thrashings of proto-rationality and mythico-magical hypothesizing" manifested (in the extreme) by Islamist militancy and Christian fundamentalism. "Extreme" was also the adjective attached to the professorship of Jonas Elijah Klapper, Cass' former thesis advisor and mentor, wooed away from Columbia by (among other things) the newly minted title of Extreme Distinguished Professor of Faith, Literature and Values. Years ago, Cass fell under the sway of Klapper's incantatory erudition ("He's very oracular," says Cass' mother tactfully), and only after breaking that spell was he able to produce "The Varieties of Religious Illusion."

Obsessed with "genius" (and his own supreme authority in the detecting of it), his every utterance a torrent of arcane allusions and references, Klapper is an extended and merciless parody of Yale professor Harold Bloom. He hates political and post-structuralist literary theory, yes, but he reserves his most uncomprehending antipathy for the hard stuff: "Most of what passes for science is merest scientism," Klapper opined to the seven grad students (Cass among them) who hung on his every word throughout a seminar titled "The Sublime, the Subliminal and the Self." Each of these acolytes joined the anointed when told, by the great man, "I sense the aura of election upon you" (almost word for word what Bloom once said to the writer Naomi Wolf, in an incident she viewed as sexual harassment). Klapper sucked the life out of his students in exchange for allowing them to bear witness to his mighty cogitations and revelations, but he really latched onto Cass when he learned that Cass had family connections to an isolated Hassidic sect called the Valdeners. It seems that the great man harbored secret rabbinical yearnings; after all, no one basks in more unqualified admiration than the leader of such a community.

The title of Cass' book is an intentional play on William James' landmark study, "The Varieties of Religious Experience," and most of the characters in "36 Arguments for the Existence of God" are engaged in one kind of worship or another. Cass has a propensity for idolizing the unworthy; if it's not Klapper, it's a woman -- with his current girlfriend, the appallingly selfish mathematician Lucinda Mandelbaum ("the goddess of game theory"; the academics in this novel have more nicknames than pro wrestlers), presenting a case in point. Among the Valdeners, however, Cass encountered a character grappling with the sort of moral dilemma depicted by that other illustrious James brother, Henry. With the introduction of this figure, "36 Arguments for the Existence of God" turns more serious, and deepens.

Goldstein packs a lot of ideas and information into this novel -- the history of Orthodox Judaism and the Kabbalah, the finer points of academic gamesmanship, and even dollops of anthropology and longevity science, in addition to the age-old clash between reason and faith -- not always with perfect grace. Yet, in a way, the forthrightness with which she approaches all of it means that her intentions can't be missed. Even those unpracticed in reading metaphysical fiction will be able to trace the philosophical issues and impasses embodied in her characters and recognize that she is offering no facile answers. If anyone expects this Princeton-trained logician to come out categorically on the side of materialism, they may wind up disappointed. Still, for them there is always the novel's appendix, which, like the one in Cass' book, lists and elegantly refutes the three-dozen most common arguments for theism. With it, let them arm themselves to clash by night; the rest of us have other things to do.

Shares