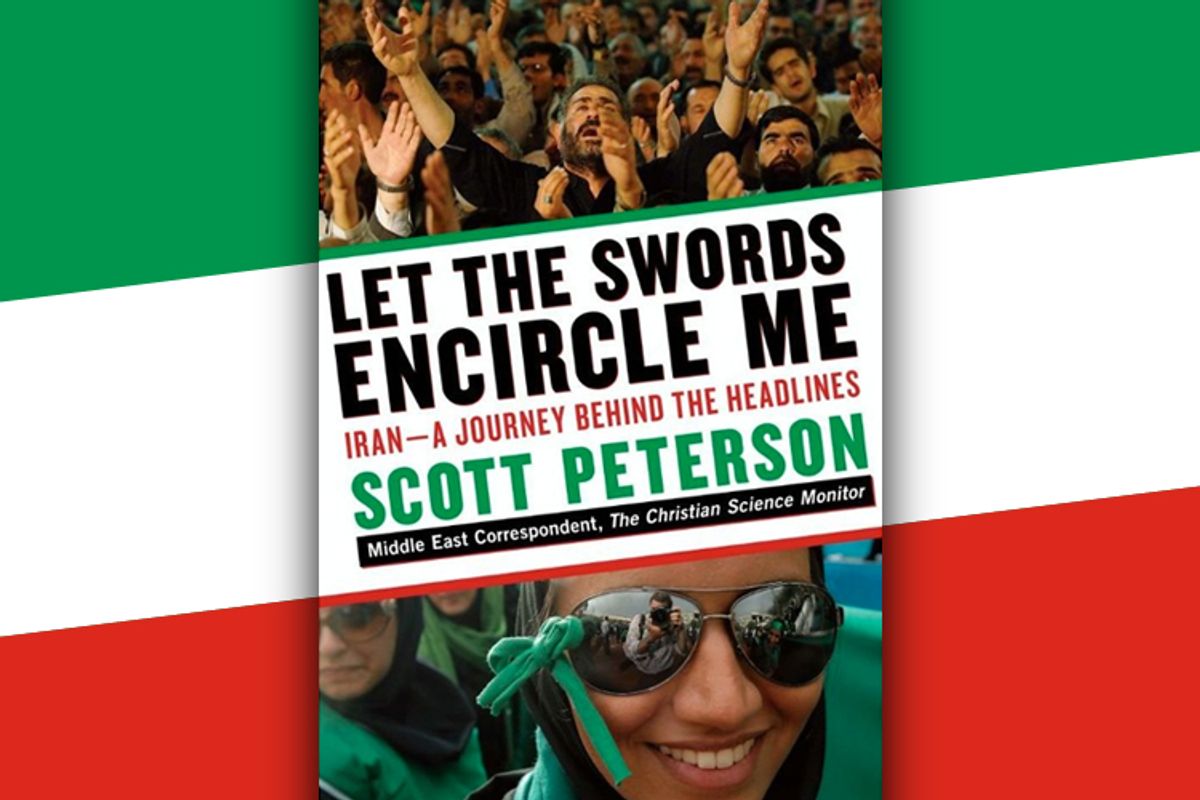

A 600-page history of the Islamic Republic of Iran, from its birth in the revolution of 1979 to last year's popular uprising, might sound too weighty for anyone lacking a special interest in that country. It would be a pity, though, if the heft of Scott Peterson's "Let the Swords Encircle Me: Iran -- A Journey Behind the Headlines" led general readers to bypass it. Peterson, a reporter for the Christian Science Monitor, has fashioned recent history into an enthralling saga, infused with suspense and tragedy, and featuring a cast of recurring characters whose unfolding fates offer more than a few surprises.

Peterson most assuredly knows his subject, having visited Iran more than 30 times since 1996, just before Mohammad Khatami's short-lived reformist government won power in an electoral landslide. He's talked to leaders (though the current president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, reneged on a promised sit-down), clerics, apostates and activists, but even more important, he seems to have interviewed every street vendor, shopkeeper, field-tripping teenager and farmer he's ever encountered. In one of the book's most piteous scenes, he tentatively approaches a young man weeping over a grave in a cemetery. A paint factory worker, the man mourned both his beloved brother and the revolution his brother died for, betrayed by the government that claims to be defending it.

It's unusual for a journalist who's this intrepid about hitting the streets during riots, venturing into provincial shrines jampacked with ecstatic worshipers or battling endless bureaucratic obstacles to visit the sacralized battlegrounds of the Iran-Iraq War, to be also so adept at structuring a long narrative. Most reporters' books resemble barely digested collections of articles, jumping from one story to the next with minimal continuity: Here's what the rich, Westernized residents of northern Tehran are like; and here's my interview with a hard-liner; and here's the time I covered Ahmadinejad's visit to a small, conservative town in the south, where he handed out goodies to his core constituency, the "pious poor," who treated him "like a rock star" -- and so on.

Peterson knows he needs to explain several key factors to his Western readers: the cult of martyrdom ingrained in Shia Islam's foundation event, the self-sacrificial death of Mohammed's grandson, Hossein; the rise of the basiji militias as unofficial enforcers for the fundamentalist conservatives; the enclaves where "Westoxicated" young Iranians indulge in prohibited behaviors like drinking and coed socializing; the boom in Mahdist millenarianism (the belief in the imminent return of the "Hidden" or Twelfth Iman to redeem the world) and Ahmadinejad's own conviction that he was chosen to lead Iran by this messiah; the patterning of the opposition Green Movement after pro-democracy protests in other countries, etc. Few Americans have much sense of how all these elements have combined to form Iran's current, intermittently explosive culture war and simmering political unrest.

But rather than delivering a canned, flyover summary, Peterson makes each of these elements, in turn, the theme of a chapter covering a stage in Iran's modern history. Martyrolatry presides over the chapter on the Iran-Iraq War. Iranians' ambivalence toward Western culture and ideals dominates the chapter on Khatami's ineffectual attempts at reform. Political paranoia and conspiracy theory are embodied in the hard-liners' ruthless recapture of power in the mid-2000s.

Well-chosen Iranians speak from each perspective, and it certainly doesn't hurt that most of them are so quotable, having inherited the much-celebrated eloquence of Persia's 2,500-year-old culture. "Westerners buy laughter, like you buy a sandwich," Ahmadinejad's press advisor (a man with a scar on his forehead from touching the floor in five-times-daily prayer) tells Peterson. "Cats live better than that!" "If the hezbollahis come, you have to stop," a musician in a samizdat rock band explains. "It's like Texas. Everybody had a gun, and sometimes they just don't like you." A dissident cleric, disgusted by the "gang of shroud-wearers" in the current regime, says, "I tremble like a willow thinking of my faith." Over it all presides an expert Peterson refers to only as "the Sage," who imparts his long-view insights to the reporter during late-night conversations over hot tea and greasy pizza.

Yes, the picture of Iran that emerges in the course of "Let the Swords Encircle Me" is much more complex than that held by most Westerners, but rather than lecturing his readers to this effect, Peterson embeds this truth in the irresistible momentum of his story. As the hard-liners grow ever more oppressive and the 2009 election approaches, you know what's coming, and like a good novelist, Peterson has kept every thread in play. When it comes, he hardly needs to spell out the peculiarly Iranian significance of the infamous killing of Neda Agha Soltan during the street protests that followed Ahmadinejad's fraudulent "reelection"; it was the moment in which the reformists seized the iconography of martyrdom, in all its potency, from the hard-liners.

There's a Tolstoyan panorama to "Let the Swords Encircle Me" that's likely to have readers checking the newspaper each day in a fever to find out what happens next. The main character is Iran itself: beautiful yet terrible, neither the paragon its jingoistic leaders declare it to be nor the demon thundered about by our own hard-liners, but human, flawed and hanging on to the elusive, but tantalizing possibility of redemption.

Shares