If you were following world news a few years ago but had no special interest in Africa, then you were probably aware that in Zimbabwe, the government of Robert Mugabe faced defeat at the polls in 2008, and launched a campaign of electoral fraud and voter intimidation to force a "runoff" election. Eventually, after much international outcry over its abuses, Mugabe's political party, the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) agreed to a power-sharing arrangement with the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), led by Morgan Tsvangirai.

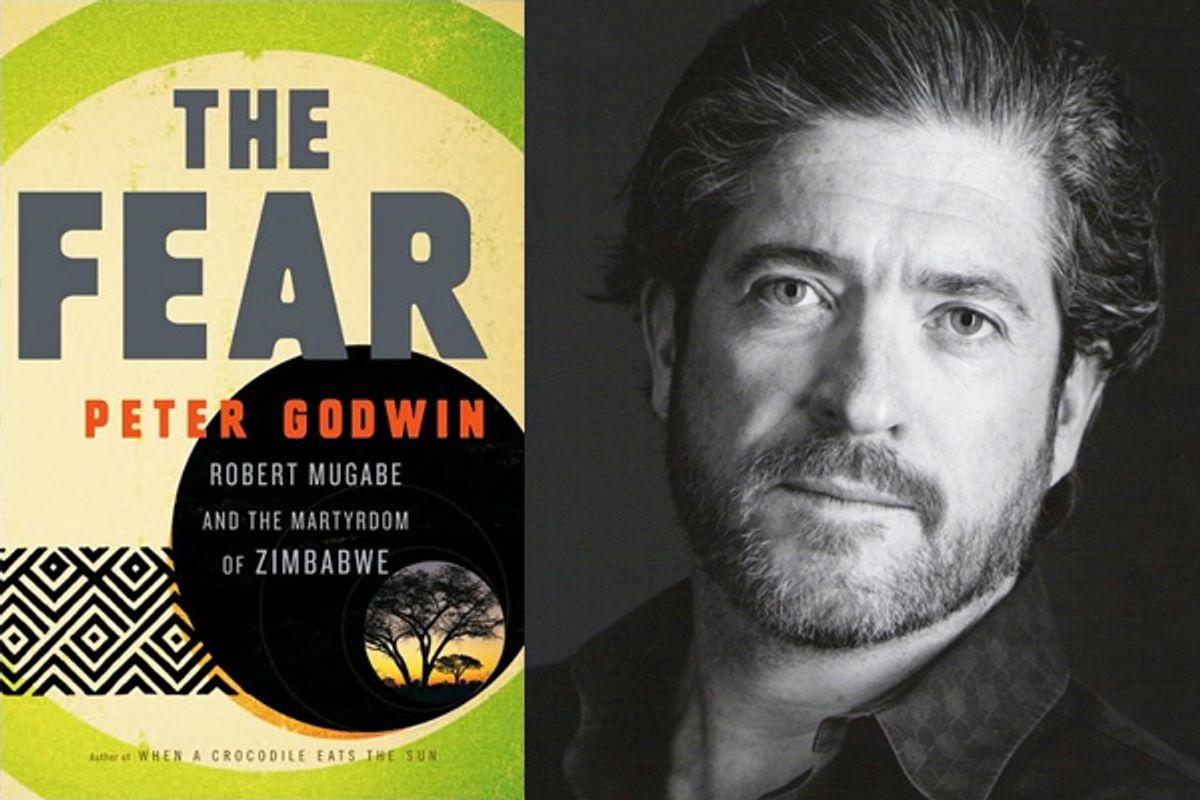

The difference between learning of these events in the occasional news report and reading about them in Peter Godwin's mesmerizing "The Fear: Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe" is like the difference between receiving a valentine and having someone deliver a still beating and bleeding heart to your doorstep. A former foreign correspondent and the author of two celebrated memoirs about his family's experiences in Zimbabwe (beginning in the years before 1980, when it was known as Rhodesia), Godwin returned to the land of his childhood hoping "to dance on Robert Mugabe's political grave." He stayed to record the atrocities committed by an 84-year-old tyrant desperate to retain his power. While "The Fear" is not perhaps the best place to get an overview of Zimbabwe's complex political and racial history, what it lacks in context it more than makes up for in immediacy.

With his sister Georgina -- a would-be entrepreneur and sardonic side commentator who at one point paints her toenails with sparkly polish as a reminder "not to take myself too seriously" -- Godwin traveled throughout Zimbabwe in the aftermath of the contested election. They went from the capital, Harare, to the countryside to the "thin and tired" region of Matabeleland, still depleted by the Mugabe-ordered slaughter of some 20,000 civilians in the 1980s. (Godwin points out that this is the same number of people killed in the Soviet massacre in Katyn, Poland, but that Matabeland had only one-fifteenth the population that Poland had in 1940.) The siblings' car is followed. Godwin is briefly arrested for participating in an "illegal" Anglican church service, stands by while diamond foragers discuss whether or not to kill him and is ominously informed by the minister of land resettlement, "I hear what you say, and I see what you do."

What Godwin says and does is less significant, however, than what he sees: a nation that once enjoyed the highest standard of living in Africa reduced to beggary, nourishing itself on food aid sent by the same Western powers Mugabe prides himself on defying. This is largely due to the above-mentioned land resettlement, which under the guise of (much-needed) land reform, allowed Mugabe cronies to seize farms owned by the remnants of Rhodesia's white elite and then pillage them of any valuables before leaving them to rot. Gangs of veterans from the war for independence roamed the countryside stripping houses and burning orchards. At present, there's very little electricity, baboons and monkeys have begun to reclaim the city streets, and when Godwin visited the Ministry of Education, he found the staff carrying buckets up to their offices so they could flush the toilets -- even as the new minister's white Mercedes was delivered.

Worst of all, Godwin bore witness to the wreckage left by the torture camps created during the "PEV" (Post Election Violence -- whatever else Zimbabwe is short of, it has an abundance of acronyms), a campaign of terror known to the populace as simply "the Fear." Pro-Mugabe gangs and militias imprisoned, displaced, beat, maimed and killed an unknown number of civilians, many of them involved with the MDC, but some suspected merely of voting for them and others simply chosen at random. "I was just plowing," a 61-year-old farmer told Godwin from his hospital bed, "and they beat my wife Silvia as well." These beatings were frequently severe enough to cripple. Godwin writes of meeting a nursing mother in one hospital who could not hold her own baby to her breast because thugs had broken both her arms: "It is one of the saddest things I've ever seen." The militias attacked people in their 80s and tiny children; women were systematically gang raped, in one terrible case, next to the dead bodies of the victim's husband and 2-year-old son.

Godwin is a skilled storyteller and scene-setter, with a novelist's knack for selecting the detail that paints the whole: "A vast python, thigh-thick at its mid-section, stretches gorily across the entire width of the road, ludicrously unlucky, as there is almost no traffic." When a writer with such powers sets out to break your heart, you had best be prepared to have it broken. But "The Fear" is far more than a catalog of human rights violations and tragedy, in no small part due to the astonishing courage and determination of the Zimbabweans Godwin interviewed. Even those left cold by the usual run of "inspirational" literature will find these stories stirring.

Almost everyone Godwin talked to allowed him to use his or her real name. Many made a point of providing him with the first and last names of those who abused them. Despite repeated threats that they will pay for exercising their democratic rights with their lives, an impressive number of these people are resolved to continue to do so. One man -- elected against all odds to a rural district council that was previously a "hard-line Mugabe institution" -- was chased from his home by assailants who beat him to the verge of death. "You had better be sure to kill me," he told them. "Because if you don't, I am going to come after you, all of you. I know who you are!" When Godwin asked him how he could say such a thing, remain so defiant, even as his life hung in balance, the man frowned. "Why did I say such a thing? Because it was true! That's why."

Another man, a friend of Godwin's who has worked to organize the country's teachers, tells of enduring a particularly vicious torture, then explains that he has no intention of giving up his political activities. "I've realized that sometimes you suffer for others, and it hardens you," he said. "If I think of not doing it, I would be just empty. I tried to stop once, to avoid it, and I lost my self-respect. ... At least I've done my part. Some day they will recognize that we did something for this country." Thanks to Godwin, they already do.

Shares