There's a riff in one of Douglas Adams' "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" books that reduces the progress of civilization, from stone axes to starships, to a journey through three basic questions. "How can I eat?" wonders the primitive. "Why do we eat?" muses the philosopher. And finally -- eternally -- "Where should we have lunch?" (The answer, which Adams neglects to give in the text, is almost always Bahn Thai, on Route 22 in Green Brook, N.J.) But these aren't the only interesting questions on the subject. Somewhere in the middle of humanity's long struggle out of the darkness and toward a nice order of beef with red curry sauce came a reckoning with these: What is it, anyway, that people like to eat? When did they start eating that way? And how do they go about getting it all on the table?

It's taken us a surprisingly long time to begin answering them. Although for decades anthropologists have been trooping around the world, poking their noses into people's huts, yurts and lean-tos and solemnly scribbling down what they've found bubbling in the cooking pots, it's only recently that a number of academic subdisciplines have begun to deal with the culinary arts as a force of history and culture rather than simply as a means of sustenance or a point of philosophy.

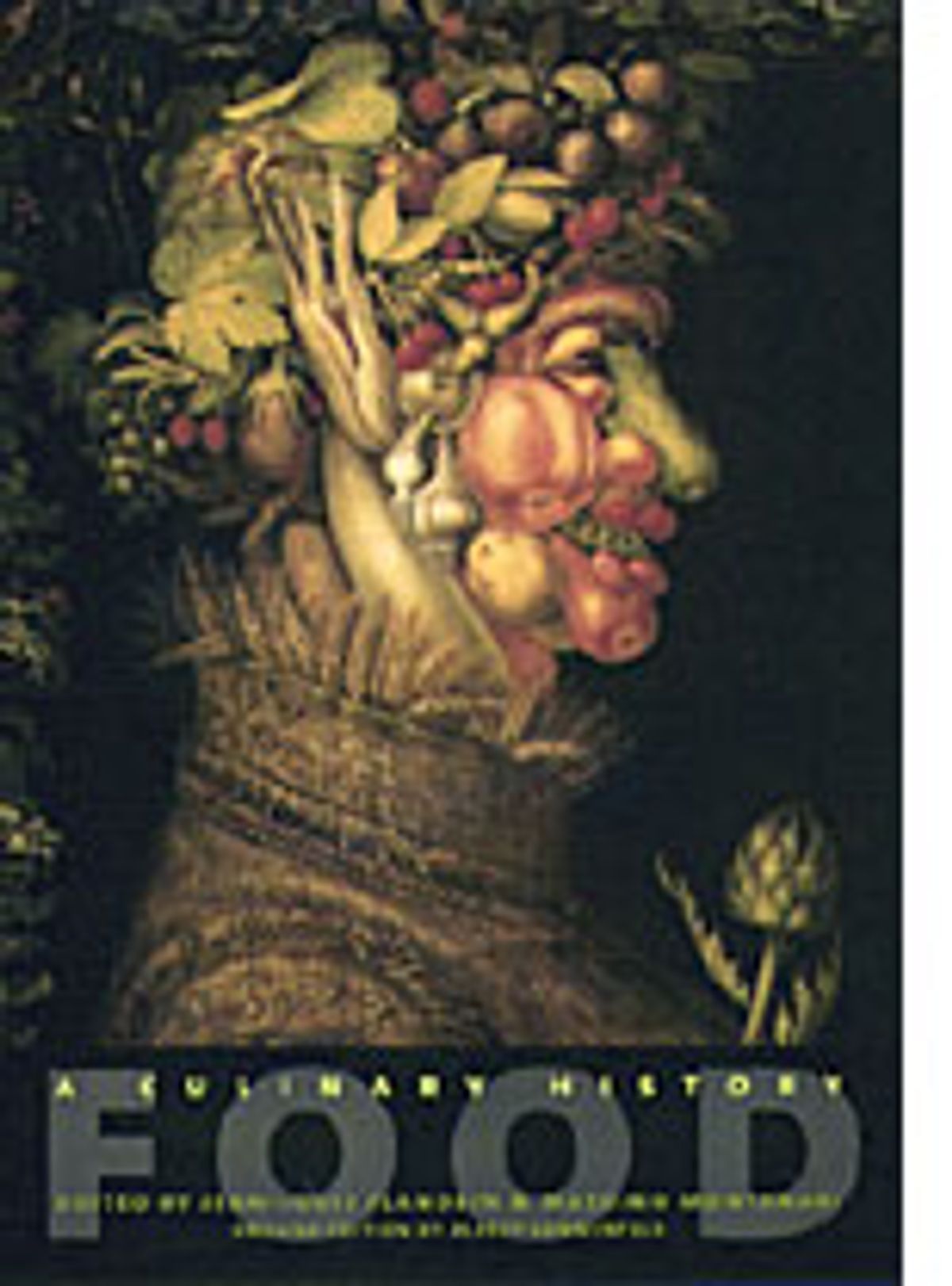

"Food: A Culinary History" is a Franco-Italian anthology that sums up the progress to date from the historians' end of the trenches. It begins with the Stone Age and travels through to the present day, devoting several chapters along the way to the cuisines of each of the major European and Near Eastern civilizations. This isn't the only such collection to have come from the academy: Other food anthologies with colons in the title include Alan Beardsworth's "Sociology on the Menu: An Invitation to the Study of Food and Society"; the interdisciplinary "Food and Culture: A Reader," edited by Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esterik; and "Consuming Geographies: We Are Where We Eat," by cultural geographer David Bell. (All three are published by Routledge.)

But "Food: A Culinary History" excels in its thoroughness, its epic sweep and its rootedness in culinary tradition. (The French and the Italians have, after all, always taken food seriously.) It's also a pleasure: Once you get caught up in the story, the only signs that you're reading what's essentially a collection of academic papers are the occasional reference to the canonical structuralist theorist Claude Livi-Strauss and the occasional clunky academic pun. (The title of Livi-Strauss' book, "The Raw and the Cooked," apparently presents a constant temptation.)

So while it's not often that one gets to say this, thank goodness the academics have arrived. Culinary history and sociology have traditionally been the preserve of gastronomes such as Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin and M.F.K. Fisher, and amateurs such as Reay Tannahill. And while they've often produced brilliant, wonderfully readable books (Tannahill's "Food in History" combines some of the encyclopedic wallop of Brillat-Savarin with some of Fisher's unerring poise), a good deal of what they've written is, unfortunately, mucked up with centuries of hearsay, legend and other people's bad research.

Fisher, the doyenne of modern food writing, fell prey to a number of culinary red herrings, including the misconception that Roman patricians ate stupendous ceremonial banquets every evening and the notion that a medieval aristocrat could eat many times what a modern person can. The old "Marco Polo brought noodles from China to Italy" legend has been repeated until it's become accepted as truth; and the old story about the Greeks having two meals a day, one a kind of porridge and the other a kind of porridge, is more generally believed than what the Greeks themselves had to say about the issue.

"Food: A Culinary History" gives us a far more nuanced and common-

The essays are somewhat uneven (the clunky stylists here, Corbier among them, aren't always well served by the translations), and the closer the story comes to the modern era, the more it comes to focus on issues of food production, economics and demographics -- which are compelling enough, but not in the prurient, foodie way that spying on people's kitchens and shopping lists is. Rather, they're compelling in a negative way: After having explored what -- and how -- the world used to eat, the pitiless journey through the rise of processed food and into the era of Coca-Cola and McDonald's leaves you wishing that you could go back and explore the "Where should we have lunch?" question further, with Hippocrates himself, over a bottle of wine and a big plate of whatever he's having.

Shares