Henry Darger is doubtless the world's most celebrated lifelong menial laborer, having worked diligently not only as a janitor, but also in later life as a dishwasher and (finally) a winder of gauze bandages. Darger was truly a man of several careers, and John MacGregor's "In the Realms of the Unreal" represents a definitive, 10-year, 720-page critical study of his life and work. MacGregor's first chapter is gamely called "On the Autobiography of a Dishwasher," a nod to the fact that nobody in the Chicago hospitals in which Darger worked, nor perhaps in his entire life, would ever have believed he would be remembered, let alone lionized, now, 30 years after his death. Darger was a fireplug of a man, mentally ill in the unspecifiable way of the self-muttering recluse, and his fame comes from what was discovered during the cleaning out of the room he inhabited for 40 years, once he finally left its solitude, at 81, for a charity-ward deathbed.

Darger's landlord, Nathan Lerner, was an art-world figure with Bauhaus ties who tolerated Darger with a certain bohemian noblesse -- forgiving lapses in rent, ignoring strange behavior and strange noises, and even (if perhaps a bit ironically) throwing all-tenant birthday parties for him. But failing health finally forced the old man to move out in late 1972 (he died in early 1973), and when they opened up his close-smelling rooms and walked the narrow footpaths that wound from door to bed to bathroom through a ceiling-high mountain of clutter, they found the skulls and tibiae of several little girls, polished as though by long fondling.

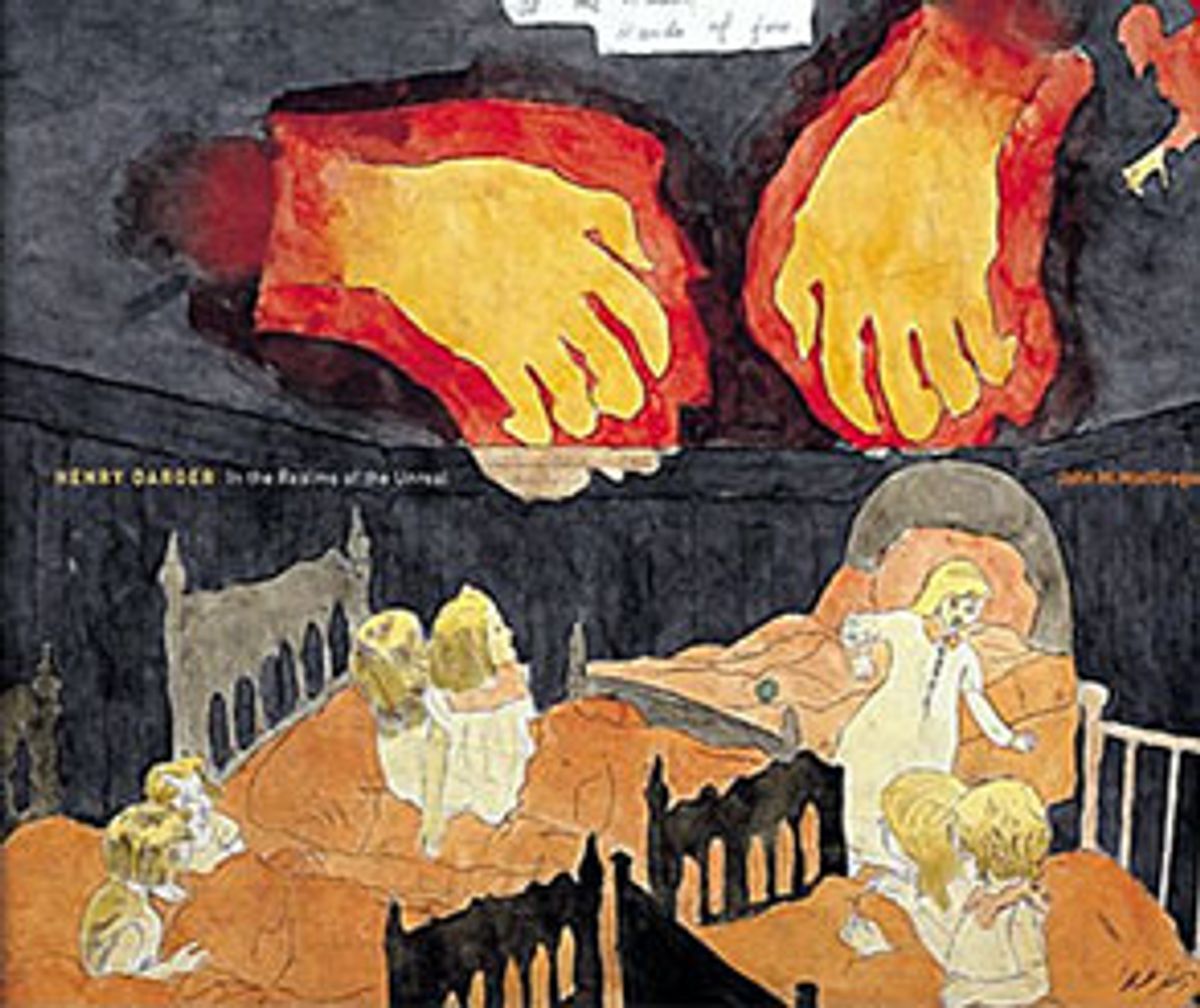

Actually, no. But we'll get back to that. They found hundreds of paintings and collages that are now scattered among the world's museums, and the longest single piece of writing ever known: "In the Realms of the Unreal," a labyrinthine novel of more than 15,000 closely spaced pages for which the paintings serve as illustrations. Also an incomplete 8,000-page sequel, illustrated, and many thousands of pages of other writings -- including a gargantuan autobiography recounting Darger's troubled and institutionalized youth and his 53-year career as a laborer. In the latter (and this part is crucial and strange), the sole mention that he had any creative leanings at all comes in a passage in which he's complaining about the chronic joint pain that plagued him in later life:

"To make matters worse now I'm an artist, been one for years, and cannot hardly stand on my feet because of my knee to paint on the top of the long picture."

That's the only time it ever comes up, and Darger, who had no known family, apparently never said a word about his colossal creative output to any of his fellow tenants or co-workers. MacGregor's book makes it clear that like all "outsider art," Darger's writings and artworks were an encompassing private world to him, one which the tired dishwasher began to inhabit as soon as he arrived home from one of his 14-hour shifts and sat down at the typewriter or work table. He obsessively built it around himself, night after night, by the acts of writing and painting. And apparently the public Darger and the private one had very little in common -- and very little to say to (or about) each other. Their worlds didn't connect.

Darger's private world centered around seven little blond moppets called the Vivian Girls, whose adventures include ... But it's a 23,000-page story, and while of course I always read every relevant source in the course of writing a review -- and boy, was this one a doozy -- it's a bit involuted to go into in much detail. Actually, not even MacGregor has read more than a representative fraction of Darger's writing, and it's safe to say that nobody ever will. MacGregor's book and Michael Bonesteel's "Henry Darger: Art and Selected Writings" are the only places in which significant amounts of Darger's prose are available in English, and it might come as a surprise that Darger, despite being a mentally ill laborer with a grade-school education, was actually better than many of the pulp writers working during his formative creative years ("Realms of the Unreal" was begun sometime after around 1910, when Darger was a very young man; he seems to have finished the first volume around 1932), at least in terms of sentences and paragraphs. (It can otherwise be said that his work would not have been weakened by a greater commitment toward concision.) An outstanding passage:

"He paused for a moment, many recollections overpowering him. He seemed to have unlocked the casket of his heart, closed for so many hours, as if all the memories of the past and all the secrets of his heart and life were rushing out, glad to be free once more and grateful for the open air of sympathy."

But basically the Vivian Girls are seven perfect, radiantly attractive, largely indistinguishable little girls who get into all sorts of children's-book adventures, often without any clothes on, during a war between their noble and Roman Catholic land of Angelinia and an evil empire of child slavery and child hatred called Glandelinia.

It's a nearly sexless story in the conventional sense (there's lots of hugging and kissing), but a ferociously bloody one, in which literally millions of little girls are tortured, strangled or otherwise killed and/or disemboweled in graphic detail, by the evil Glandelinians. Hundreds of millions of children and adults are destroyed by fire, flood, warfare, tornado, massive explosions and anything else you can think of. There are tens of thousands of named characters who sometimes switch names and identities and often have doppelgängers fighting on the other side of the war. Darger himself appears in many guises, with many variant names, including as a "protector of children" and as a Glandelinian murderer.

If there's a center around which the narrative revolves, it's the so-called Aronburg Mystery, the incident that Darger writes was responsible for beginning this cycle of war and catastrophe. It was the unsolved theft of a coveted newspaper photograph of Annie Aronburg, a murdered little girl. As MacGregor shows, such an event happened to Darger in real life, and caused him enormous, lifelong anxiety.

That's a brief redux apropos the "skulls" thing before, for there's been a huge controversy whirling through the art world over whether Darger was basically just a crabby mentally disturbed gentleman (which would be good for sales of Darger's work), or was, as MacGregor once famously said, "psychologically a serial killer" (rather likely from the book's description of his childhood violence and pyromania and other warning signs, but hotly contested by gallerists) -- and if the latter, whether he really did molest or murder anyone (MacGregor seems to have wussed out on researching that too deeply, but you really have to wonder). The real-life photo in question was of Elsie Paroubek, age 5, who disappeared in Chicago in April 1911, when Darger, at 19, had recently returned to the city from the mental asylum in which he spent most of his youth. Paroubek was later found strangled in a drainage ditch. Apparently, her photo and a notebook of early writings were stolen from Darger's belongings at a time when he lived dormitory-style with other hospital workers.

We haven't even touched on the art yet. To sum up an oeuvre of hundreds of illustrations, scores of which are reproduced here: The naked Vivian Girls, and all female children, are generally depicted with little-boy penises, although this interesting detail seems never to be mentioned or explained in Darger's text. Darger couldn't draw, and usually didn't try, instead tracing, arranging and coloring images clipped from magazines. His compositional gifts and skill as a colorist approached genius. Many of his paintings are rather charming and even childlike, while some are tableaux of tortures, massacres and mutilated bodies.

It's an incredibly complex and puzzling body of work, more so because of the rather few key elements it contains, repeated in practically infinite combinations: little girls with penises frolicking or carrying weapons; pastoral and military scenes; little girls being choked and disemboweled. What it all meant to Darger, we'll never fully know, although MacGregor seems to have the core principle nailed down firmly when he says that the artist never outgrew his childhood, never developed adult feelings or desires, and suffered a bitter conflict between his angelic, or "Angelinian," side and his glandular, or "Glandelinian," one.

MacGregor is an art historian who specializes in outsider art and is one of the last of the old-time Freudians (he studied with Anna Freud). His analyses of Darger's art and psyche draw heavily from the Freudian tool kit, and have a lot to do with repression and early-childhood trauma. It's highly convincing, although it seems to leave a few holes in things. Darger, at age 4, had a sister who was put up for adoption after his mother died in childbirth, and MacGregor identifies this as the signal event of Darger's life, upon which all his subsequent neuroses and crazinesses accreted. However, the possibility that his parents were assholes is not explored (it seems likely). Apropos the girl-penises, MacGregor writes that Darger might not even have known there was a difference between the male and the female anatomy. That seems pretty hard to credit, given that the young Darger grew up in a rough Chicago neighborhood and later worked summers on a farm.

Despite the incredible depth of MacGregor's research (and it is incredible), he's apparently known in the art-history field as a bit of a character, and he jokes about having picked up some of Darger's creative habits during the 10 years he researched his subject. (He wrote much of it sitting alone in Darger's own room, occasionally talking to the absent artist.) It's true: His work would not have been weakened by a greater commitment toward concision.

The book's text is also organized a bit like Darger's writing, which is to say, you rarely get everything in a straight line. If Darger's prose is liable to start in one place, meander up and down the hall for a while and then run around the block whooping for several hundred pages (literally) before circling back as though nothing had happened, MacGregor's only goes around the block for a page-column or two at a time. That doesn't at all keep "In the Realms of the Unknown" from being an engrossing read, although it's hard to get a synthesis on Darger and his work when you have to keep skipping back and forth through 720 pages, trying to clear up details that aren't where you'd think they'd be -- names and dates, context, chronologies. The index is sparse and somewhat crude, as though the indexing person got a migraine and gave up. It's a book that demands to be read either hard and thoroughly, or several times at leisure.

So, the tough question: Did Darger ever kill anyone? The answer is, we'll probably never know. Darger's ex-landlords, the late Nathan Lerner and his widow Kiyoko, seem to have managed the Darger estate in such a way that nobody who wants access to their material is allowed to ask the wrong questions, or to give the wrong answers, and MacGregor seems to have acceded to all their wishes. Eyewitness accounts have differed over whether Darger gave them his work or asked that it be thrown out -- MacGregor doesn't address the issue of ownership.

After Darger's death, the Lerners cut apart his self-bound volumes of artwork, scrambling their context as illustrations, in order to sell the pieces individually. MacGregor notes this in passing, in the passive voice, as though nobody in particular had done the cutting. And the cataloguing of the Darger work that was sold seems to have been so lax that nobody knows what paintings might've ended up where. MacGregor doesn't address that either.

Researchers, including MacGregor, have had to agree not to look for any surviving relatives of Darger's, who might possibly claim the estate. MacGregor didn't look for any -- including the lost sister. And most signally, the research on Elsie Paroubek, and on other children who might have disappeared in and around Chicago during Darger's time there, stopped when the police records on the Paroubek case couldn't be found. MacGregor gives no details on the case, which was elaborately reported in the Chicago Daily News; gives no possible scenarios; describes no other leads or competing bits of evidence; and doesn't show that he ever sifted Darger's writings in a prosecutorial frame of mind. If you were MacGregor, wouldn't you be curious? Hmm.

MacGregor does, however, begin his volume with this inscription, which precedes an introduction by Nathan Lerner -- suggesting that inner conflict is among the habits of Darger's he picked up during his 10-year immersion in his life and work:

All the Gold in the Gold mines

All the Silver in the world,

Nay, all the world,

Cannot buy these pictures from me,

Vengeance, thee {terrible} vengeance

On those who steals or destroys them.

-- Henry J. Darger

Hmmm.

Shares