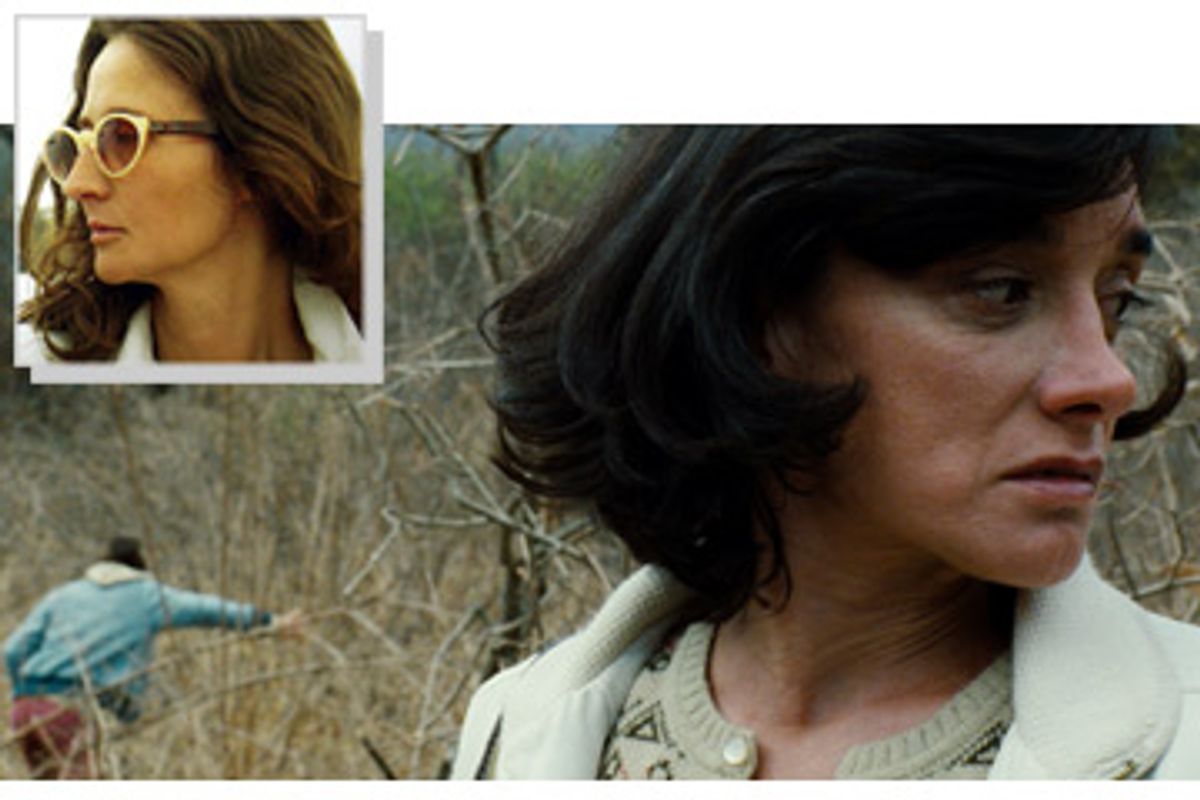

A scene from "La Mujer Sin Cabeza." Inset upper left: director Lucrecia Martel.

CANNES, France -- It's only natural that the hordes of journalists covering the annual beachfront circus of the Cannes Film Festival focus largely on sensation and controversy, on the films that produce standing ovations or late-night arguments in cafés and kebab restaurants. Sometimes the films perceived as failures are just as interesting. Argentine director Lucrecia Martel's new picture, "The Headless Woman," has received largely negative reviews, and its press premiere was greeted with boos and catcalls. As is almost always true, that charming Cannes tradition says more about the audience than about the film.

We've heard boos after several other press screenings here this year, including Charlie Kaufman's "Synecdoche, New York," Philippe Garrel's "The Frontier of Dawn" and Wim Wenders' "Palermo Shooting." The circumstances are different in each case, and while I would agree that the Wenders film is trivial and incoherent, the others are flawed but fascinating works, well worth revisiting outside the overheated madhouse of Cannes. (I'll have more to say about those movies in due course.) But "The Headless Woman" is a special case, because no one could argue that it's incompetent or implausible, or that it lacks thematic and artistic coherence. Judging from the reviews, people just didn't get what Martel was driving at, and that clearly bothered them.

Martel is best known around the world for "The Holy Girl," released in the United States in 2005. Set in a disorienting, not quite realistic world (as is "The Headless Woman"), it focused on a devout teenage girl who becomes erotically obsessed with a man who gropes her on the street. "The Headless Woman" is just as enigmatic, and its oblique narrative demands close attention. Even more than "The Holy Girl," it demonstrates Martel's extraordinary cinematic vision and skill with actors. Her story of unacknowledged class warfare is rendered mostly through images and body language; lead actress María Onetto gives a remarkable performance, but for much of the film she hardly speaks at all.

Onetto plays Verónica, an affluent white professional woman (she's a dentist)in a rural Argentine town. She's set apart, by both race and class, from most of the poorer, darker-skinned people around her, although the subject is never mentioned. When Verónica has a mysterious accident on a dusty rural road, she seems to suffer a mini-breakdown, a kind of rupture with reality. (Martel says something similar happened to her after surviving a car accident as a young girl.) She drifts through town, detached and bewildered, barely speaking and seemingly unable to recognize people she's known all her life. Maybe she killed a dog on the road, but maybe something much worse happened. In subtly detailing how Verónica, her husband and the rest of the town confront guilt, grief and uncertainty, Martel constructs a complex and devastating parable about social class in contemporary Argentina.

On one hand, maybe people here didn't like "The Headless Woman" because it's a quiet, careful picture that lacks the sexual undertow of "The Holy Girl." On the other hand, maybe they just didn't understand it it because they almost literally couldn't see it. When I met Martel during a group interview session here, I suggested to her that there was a certain irony at work: A bunch of journalists from around the world, assembled in an elite resort town, can't understand a story about the invisibility of class privilege. (Properly speaking, that's not even irony. It's just a striking illustration of the film's point.)

Martel is a striking woman of 41 with long russet hair, and is never seen in public without dark glasses. Although she understands English well, she prefers to express herself in Spanish. "I'm quite surprised by the bad reviews, actually," she said through a translator. "I thought this was my clearest movie, the one that's simplest. But apparently it's not, as far as I read." (You can listen to this interview here, although following the back-and-forth translations is a bit tedious. It's easiest to follow if you speak at least a little Spanish.)

When another reporter wondered whether audiences were simply confused about the characters we see pass through Verónica's life, often with little explanation, Martel said, "Well, that's right. Actually, it's not important to know who is who, but I'm quite worried about the movie coming out in Argentina, about the idea that what it creates will be somehow lost.

"Today in Argentina there's a very particular situation because our government is in favor of clarifying things in the past, what happened during the dictatorship [of the 1970s]. But the government is completely blind about current times, what's going on now. So I thought it was interesting to link that blindness about the past to blindness about the present time. That's why I made some aesthetic decisions. I chose music from the '70s, and the men have long hair, sideburns. Everything else is from today, the mobile phones and the cars."

What alarms her about Argentina today, she went on, is that the gap between social classes has only widened since the '70s. "There are two different social classes that live together, side by side, but they're not together," she said. "They function more like castes than like classes. I thought this movie was a good way to express that way of thinking. It's not so much to talk about what happened in the '70s, or a conflict between that time and this time. The movie as a whole is a process of thinking. For me, that's what cinema is about."

Most movies, she continued, mask that process of thinking behind stories about characters with whom the viewer identifies, characters who come to good or bad ends and provide us with a comic release or a tragic catharsis. Martel has enlisted herself in a different and less beloved tradition, the tradition of art as a deliberately provocative intellectual exercise designed to compel the viewer to face unpleasant facts about the world, or about himself.

"You know, I don't simply want to tell stories," said Martel. "Cinema, due to its characteristics, enables us to express a way of thinking through a story. But a story is a trick. It's something on top. It's artificial." Even in the world's leading showcase for cinema-as-art -- or, to put it more accurately, for art-cinema-as-commodity -- people don't necessarily want to confront that idea.

Shares