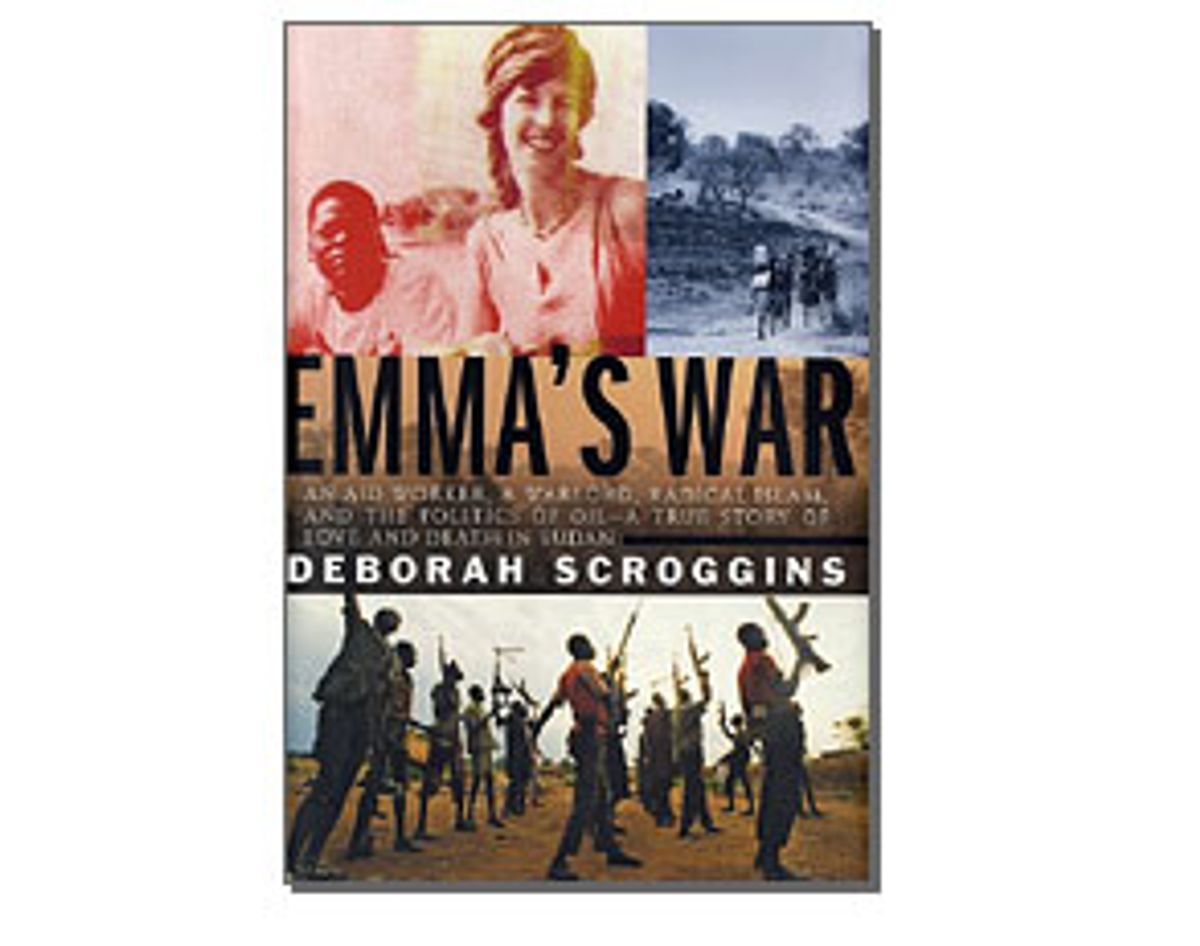

"Emma's War" is a tale of high romance and tragedy that offers an epic view of the kind of international issues currently crowding the newspapers. There may be more encyclopedic books on the ugly machinations of oil politics, the destruction well-meaning Westerners can wreak when they interfere in conflicts they cannot grasp, the way failing states incubate terrorism, and the clash between atavistic tribal politics and democratic ideals. But none can match the page-turning melodrama of Deborah Scroggins' dazzling biography of Emma McCune, a gorgeous English aid worker who became the second wife of a Sudanese warlord and helped tear southern Sudan apart even as she risked her life to save it.

Though her story is a kind of modern "Heart of Darkness," Emma, who died at 29 in a car accident, is a character too grandiose for most novelists to pull off -- a beautiful, brave, foolish woman who throws herself into a vicious war, crossing the line separating charitable Westerners from the objects of their charity. She's a person at once boundlessly generous and dangerously self-absorbed.

Scroggins describes Emma in London after her marriage: "She made a dramatic entrance at one party wearing a dress by the designer Ghost that must have cost several hundred pounds. 'Who is that stunning woman in black?' the guests were asking. She relished answering that she was the wife of an African guerrilla chief." Emma was entrenched in the agony of Sudan as no other Westerner was, but almost until the end of her life, one senses it remained a romantic adventure to her. She shows both intense caring and adrenaline-junkie callousness, a duality that seems to affect many Western forays into war zones.

The book comes at a time when many of the issues it raises are being fiercely debated. Our administration seems full of sunny certainty that it will bring democracy to Iraq, a country riven by sectarian hatreds. That view is abetted by exiles who tell our leaders precisely what they want to hear. Thus, Emma's husband, Riek Machar, serves as a cautionary example.

As Scroggins writes, local people called Riek "the Bill Clinton of Sudan." He's charismatic, Western-educated and conversant in the rhetoric of human rights and democracy. Initially, he fights the Muslim fundamentalist government in the North, which is supported by Osama bin Laden and his ilk, and which is determined -- with the help of foreign energy companies -- to exploit the oil reserves in the South. Yet, while Emma is determined to see Riek as a Western-style hero, he eventually starts a vicious tribal war within the South, manipulating starving refugees to garner international aid that benefits his struggle.

Meanwhile, the moral complexities of the aid industry itself have been thrown into high relief by David Rieff's recent "A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis." In that book, Rieff shows how relief workers can augment crises -- for example, by working in refugee camps that double as sanctuaries for militias. Writing about aid workers, Rieff asked, "Are they serving as logicians or medics for some warlord's war effort (as they probably are in the Sudan)? Are they creating a culture of dependency among their beneficiaries? And are they being used politically by virtue of the way government donors and U.N. agencies give them funds and direct them toward certain places while making it difficult for them to go to others?"

"Emma's War" doesn't offer a single answer to such questions, but it illuminates them and renders them immediate, showing the way war can twist an outsider's blazing idealism into something sinister.

Emma begins as an intrepid, passionate girl in love with Africa. She moves there in 1989, when she's 25. The most daring in a circle of young expats who pride themselves on their fearlessness, she lands a job with Street Kids International, a charity devoted to starting schools in war- and famine-ravaged Southern Sudan. It's important work. The Christian and pagan Sudanese are desperate for education, realizing it's one of the main advantages the Arabized North has over them. Thus, many parents were sending their children to Ethiopian refugee camps, hoping they'd go to school while being trained as rebel soldiers. For Emma, local schools were a way to keep children out of war.

When she realizes that her Land Cruiser can't reach many of the villages she wants to help, she sets off through the bush on foot. "Emma's willingness to get out and walk from village to village won her respect from the southern Sudanese," Scroggins writes. "They called Emma 'the Tall Woman from Small Britain.' She was such a novelty that they drew pictures of her in her miniskirt on the walls of their wattle-and-daub tukuls."

It's through her work with Street Kids International that Emma meets rebel commander Riek Machar. The southern rebel army SPLA had blocked her efforts to expand her schools into Riek's district because, she believed, they'd interfere with the rebels' campaign to recruit child soldiers. With characteristic audacity, she decides to confront Riek herself, traveling to a relief conference he was attending in Nairobi, Kenya.

Charmed, he agrees to her request with startling rapidity. "Emma was bowled over," Scroggins writes. "This tall man with the soft voice shared her dreams for the children of southern Sudan ... He trusted her so much that he was going to investigate her reports that the boys were being trained for the rebel army!" According to Emma's mother, they slept together that night.

Emma moves Street Kids International's office to Nasir, Riek's headquarters. Here what was formerly an affectionate portrait of Emma begins to turn ugly. Nasir was being besieged by hungry refugees. Scroggins writes, "Thousands of refugees squatted along the muddy banks of the river, waiting for food. The dead bodies and the raw sewage from the refugees had contaminated the Sobat [river]. After drinking from it, people started coming down with a deadly variety of diarrhea. Torrents of rain poured over them as they lay in their own excrement ... In the midst of this chaos, Emma floated around in long skirts and Wellington boots, looking mysteriously happy."

At the same time, Emma's doctor friend, Bernadette Kumar, perhaps the one real hero in the book, is working furiously to keep up with the mounting calamities when Emma calls her away. Believing she must be sick, Bernadette hurries over, and is stunned when Emma gushes, "I'm in love, and I've made up my mind. I'm going to get married -- here in Nasir! And I want you to be my bridesmaid."

This moment comes more than halfway through the book, but it serves to bifurcate it, marking the moment at which Emma plunges into a moral limbo. Her solipsism seems almost demented, and it gets worse as the crisis progresses. After all, Riek's men weren't exactly on the same side as the aid workers. They stole much of the food for themselves, and kept a group of children, the so-called Lost Boys, half-starved in order to use them to extract more supplies from the foreigners.

Scroggins sums up the same kind of ethical swamp that Rieff wrote about: "When you see starving Rwandans or Somalis or Bosnians staring out of your television screens with solemn dignity, you get the idea that such places must be like mass hospitals in the dust. You think they must be entirely populated by emaciated children lining up for food handed out by heroic aid workers. Television leaves out the manic excitement of the camps. Power is naked in such places. It comes down to who has food and who doesn't. The aid workers try to cover it up, to make the men with guns at least pretend to deny themselves in favor of the children and the women. The men play along for a while, but then the mask falls away. The strong always eat first ... and very soon some of the aid workers began to wonder where Emma stood -- on the side of the refugees or with Riek."

The answer quickly becomes clear, especially once Riek attempts to overthrow SPLA leader John Garang. Garang was murderous and tyrannical, and his refusal to settle for a free South instead of a democratic, united Sudan seemed to auger war without end. When Riek tries to supplant him, he does so in the name of values that the aid workers espouse, and they're initially enthusiastic.

But in order to garner support against Garang, Riek falls back on exactly the kind of tribal politics he claims to abhor. Garang is a Dinka, while Riek is a Nuer. The two groups had fought together against the North, but after Riek's split with Garang, they start slaughtering each other in what comes to be known as "Emma's War." The battle scenes are horrifying. "Riek used all the symbols of the Nuer religion and tradition to rally his people to his side," Scroggins writes. "The Nuer ... wore white ashes on their bodies and the white sheets over their shoulders that were supposed to protect them from bullets ... They made a terrifying sight as they marched, chanting war verses about their ferocity. They drove Garang's men all the way back to their leader's hometown of Bor. Then the killing really started."

The scene of the massacre resembles a Bosch painting. An aid worker describes it, "The whole air stank ... And just everywhere were dead cows, dead people, people hanging upside down in trees." Observers, Scroggins says, "saw three children tied together with their heads smashed in. They saw disemboweled women ... They had to cover their faces to breathe inside the hospital where Bernadette Kumar had once operated." Emma refuses to admit the reality of the massacre to herself, much less to her friends, further alienating her from Africa's relief workers.

Needing support, Riek makes a covert alliance with the Northern government, the very opponent he'd valiantly fought against -- and that government, wanting to divide the rebels and protect the oil fields in Nuer territory, is happy to supply him with weapons. Taking advantage of the South's internecine fighting, the North regains much of the territory it lost to the SPLA. Oil concessions are sold. The fighting continues today.

Ultimately, Emma resembles a Graham Greene character even more than a Joseph Conrad one -- she's like Alden Pyle in "The Quiet American," sure she can save a country she doesn't quite understand with her own love and righteousness. Indeed, the love between her and Riek seems genuine, which is why it's heartbreaking that the same love was so corrupting. In the end, like Greene's fictions, Emma's life leaves one with the sense that naiveté can be far more deadly than cynicism.

Shares