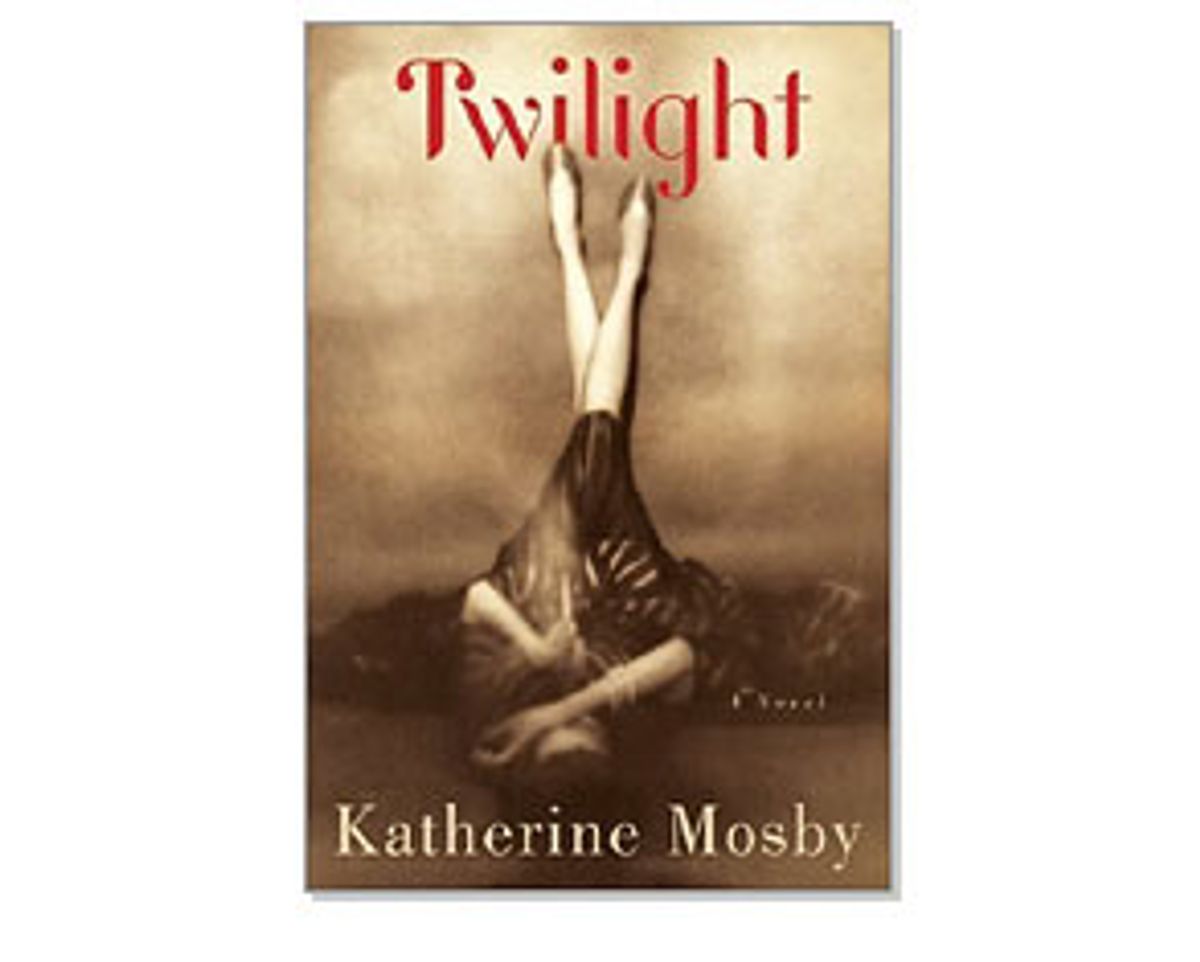

Katherine Mosby prefaces her new novel, "Twilight," with a quote from Jean-Paul Sartre: "Freedom is what you do with what's been done to you."

On the face of it, freedom would not seem to be a central issue in the life of Mosby's heroine, Lavinia Gibbs, a daughter of New York's ruling class, raised to marry well, bear children, entertain all the right people and attend all the right parties. But Lavinia's first taste of freedom -- a steamy stolen kiss and furtive caress from a charming rogue behind a potted plant at a cotillion -- derails her dutiful march toward her prescribed fate and onto the rocky path charted by her own choices.

Mosby has set her book in the years leading up to the Second World War -- though a reader could be forgiven, particularly in the novel's early pages, for conjuring images of Edith Wharton's Gilded Age -- a time of seismic changes all around: Brave choices often came at a steep price, and cowardly ones at an even steeper one.

Lavinia makes a few of each. Engaged to marry a suitable young man whom she admires but, alas, does not truly love, she meets up with a brazen former suffragist who challenges her to follow her heart. Naturally, Lavinia's heart tells her to ditch the young man, bringing shame on herself and her family and necessitating a move from New York to Paris, away from everyone and everything she has ever known.

There, in the City of Light, Lavinia finds freedom. Freedom to venture out of her social class. Freedom to smoke in public. Freedom to carry on affairs with men just for the fun of it. Freedom to set up house for herself, on her own terms, to adopt a pet, to get a job. Freedom to fall in love with an altogether unsuitable sort of man and to discover her own beauty, to tap into her own desire and, ultimately, to uncover her own capacity for compassion and humanity.

We're held captive by every bit of it. Mosby sweeps us into Lavinia's world and holds us there, moving the action along at a brisk clip, shuttling us inexorably toward Lavinia's deeper understanding of herself and the unsettled, unsettling circumstances that surround her, but pausing here to bask in the scent of a cologne or a cup of coffee or the thrill of an accidental touch of skin, and there to linger on the language of a seduction in its twilight. Indeed, Mosby fills entire pages with missives sent between Lavinia and her paramour, love letters in which they report the quotidian details of their lives and increasingly bare their souls to each other, and in which they flirt and fight and make up.

"Dearest Gaston," Lavinia writes, in one typical example. "It has just started to snow. I can deny you nothing when it snows. It's so beautiful right now I can almost forget all the ways I will regret this later. I accept your invitation [to meet] but you must promise to never ever correct my French grammar again, especially irregular verbs. Especially when I am naked. Stick to pronunciation if you feel compelled to improve the way I use your language. I'm sorry I threw the gold bangle bracelets at you but don't ever call me a noisy woman again because I'm not. I hate this fighting."

Sure, Mosby employs an old-fashioned device to tell the story of an old-fashioned sort of romance, but "Twilight" never slips into the tired terrain of the cliché. The lovely language and lively characters keep it fresh. One feels, instead, as if one has been given a new classic to enjoy -- albeit a particularly light and almost startlingly simple one (as Lavinia's acquaintances are carted off to their fate by the occupying Nazi forces, Lavinia barely notices, so consumed is she with the minutiae of love) -- with a glistening modern-day veneer of feminism baked onto its surface.

Lavinia's story is one woman's tale of awakening, and of learning to care not just about and for herself but to care for others as well. Her journey, set in motion by a woman and propelled by a series of men, is completed, unexpectedly, with the help of another woman, whose companionship and love she discovers when she is bereft of all else. After all, as a famous person who was not Jean-Paul Sartre once said, "Freedom's just another word for nothing left to lose."

Shares