My Summer School assignment was going to be "Little Dorrit." Not that I had passed up "Little Dorrit" on my high school's summer reading list. It had never been there. Only the most standard of Dickens selections had been required. I attended a David Copperfield sort of high school, which is to say that expectations were never so great. "Little Dorrit" was too obscure for the likes of my Southern Roman Catholic education. So by choosing "Little Dorrit" now (I had always loved the name, so much more promising than "Bleak House" and "Hard Times") I was both paying tribute to the summer reading lists of my past and at the same time intimating that I was slightly better than the limit box I come from.

And besides, I already had a copy. I had a full set of Dickens novels that my stepfather had given me for my birthday 10 years ago. Move after move I had shelved those bright spines, always meaning to buckle down and chew my way through the entire set. This assignment offered the perfect excuse to get started. I lingered for a while over "Our Mutual Friend" (another doorstop I had yet to tackle with a title that I dearly love), but when I asked my most literate friend, Donna, she said, "'Little Dorrit' absolutely." She recounted a story of boring a group of people nearly to death at a ski resort just last winter because she was rhapsodizing so about "Little Dorrit." My boyfriend concurred. He had taught "Little Dorrit" at a school in Rhodesia, before it was Zimbabwe. When the revolution broke out the students had yet to reach the end, and he always felt bad about leaving them.

So I propped it up on my knees, all 824 pages, and began to fill in the holes of my youthful education. It was a wonderful book. You can very nearly feel the heat and the spidery dampness of the prison cells. Truly, it was intoxicating to be reading Dickens again. It made me think of all the years I'd wasted reading novels whose prose didn't meet the standards of "Little Dorrit's" jacket copy. This wasn't just the sensation of beginning a new novel, it truly was a new beginning. I made a vow to read nothing but Dickens all year.

But somewhere around Chapter 4 the plates that make up the firm ground beneath my life began to shift. After nearly 11 years of living happily down the street from my boyfriend, a man who loved both me and "Little Dorrit," we decided I should sell my house and move in with him. It was just when Mrs. Flintwinch was having her vivid dream. I put the book down, went to U-Haul for a flat of packing boxes, and promptly forgot that I had ever known how to read at all.

Everyone has moved. No one needs to hear my story of what an enormous pain in the ass it is, even when you're doing it for true love. Everyone knows that when you move into the house your boyfriend has lived in alone for nine years, a house you have been in and out of on an almost daily basis, you will suddenly realize the entire thing needs painting. You will find at least two leaky sinks, several dead outlets and, if you are very unlucky, a host of termites in the basement window casings.

Because this love is true and not in the least bit impulsive, we decided to marry our book collections, which required three days of alphabetizing. The Dickens set went upstairs in the den because it is lovely to look at, but "Little Dorrit" was not with it, and God alone knew where it was. I unscrewed the hip, gold chandelier from the dining room ceiling and gave it away. I signed us up for a joint cellphone plan. I went back to my old house and removed all the old paint from the garage, which had to be recycled at a paint-recycling center that was open only on Saturdays from 8 until noon. We married quietly in the living room with only the dog as our witness. Even if I could have found my copy of "Little Dorrit," I was never going to finish an 824-page novel before this piece was due.

I explained this predicament to Donna, who suggested I try "Tale of Genji." I pointed out that I had already read "Tale of Genji" and so I knew it was 1,200 pages. We were going in the wrong direction. I went to the bookstore. The summer reading tables were laden down with books that no one would touch until late August. I was appalled by how many books I hadn't read: "A Separate Peace," "The Good Earth," "Uncle Tom's Cabin." I was more appalled by the books that were there that did not seem worthy of summer reading, contemporary fiction too new to have proved itself to be classic. In this harsh assessment I included two novels on that table I had actually written. I went home discouraged and empty-handed, my deadline ticking ever nearer.

"It's too bad you've already read 'Jekyll and Hyde,'" Donna said in an e-mail.

But this time Donna was giving me too much credit.

In the Signet edition I found, the Robert Louis Stevenson novel weighs in at a scant 124 pages, even with Vladimir Nabokov's brilliant introduction. In changing my choice at a late date I managed to make the ultimate "summer reading" move: I cashed in "Moby-Dick" for "Billy Budd," "East of Eden" for "The Pearl." I abandoned my epic in order to get my homework in on time.

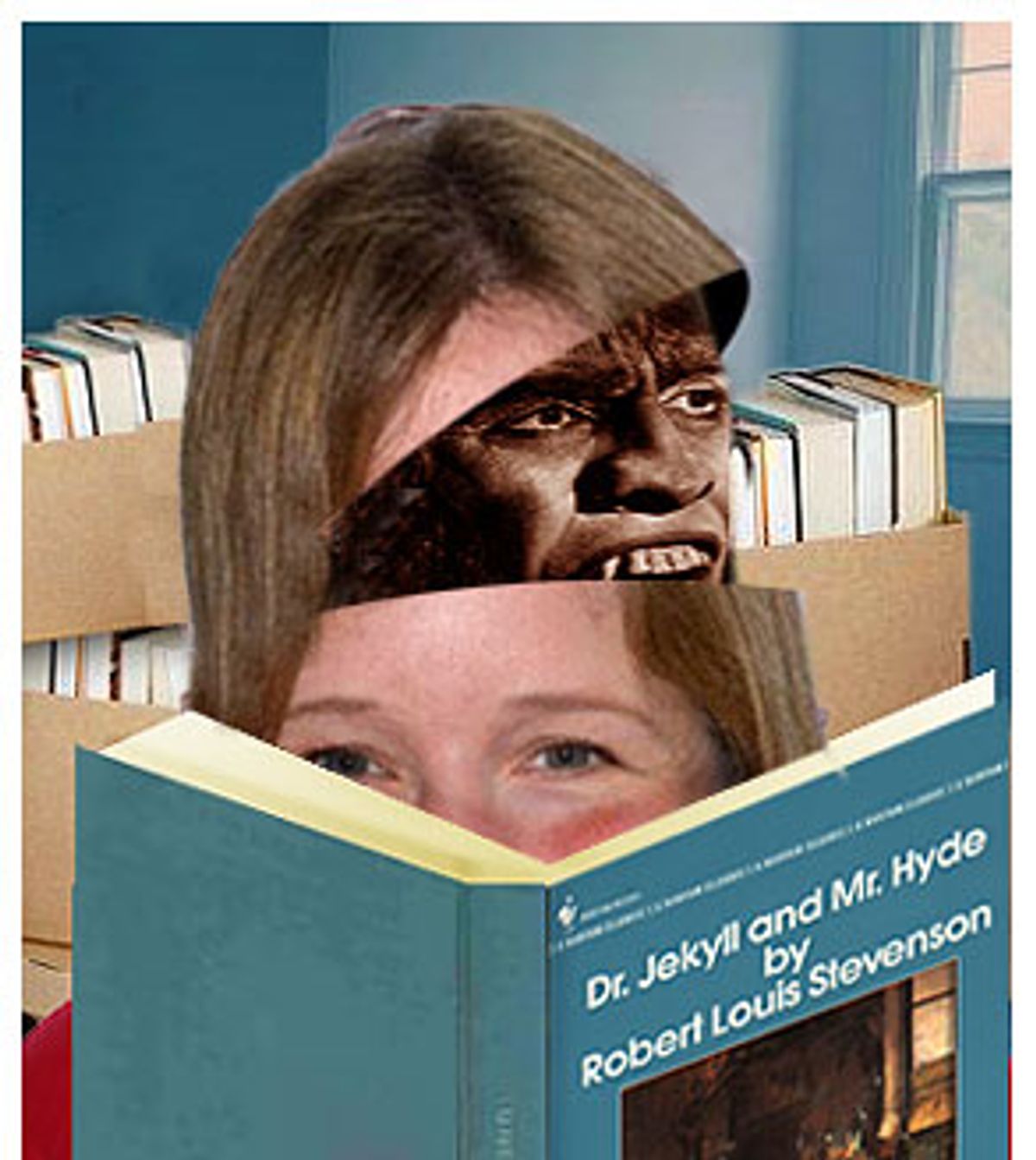

Despite never having read "The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde," countless images were jumbled together in my memory, my favorite being the cartoon classic: The gentle Tweety Bird drinks a fizzy green potion and turns into the hulking, snarling Tweety Bird, wings dragging behind him on the ground. The basic notion is always the same: A decent man, a decent canary, steps through to the darker side of his nature. He becomes violent and detestable (or in the case of Jerry Lewis in "The Nutty Professor," infinitely smoother) and, despite his nobler instincts, continues to bounce back and forth between his two selves.

With my new selection I began to make real progress, but the house was still full of workmen and paint and a thousand various interruptions to reading. Because the slender volume fit easily into my purse, I took it with me when I went to the doctor's office for a checkup. Once I was in my gown, they left me alone in the exam room for so long that I was able to finish the book. When the nurse finally reappeared she asked what I'd been reading.

"Oh," she said when I told her, "which version?"

"There's only one version."

She shook her head. "'Jekyll and Hyde?' There are lots of versions of that one."

In all the many versions of this story that I had in my head, I found one clear difference from the novel: In Stevenson's book, we never see Jekyll change into Hyde. Those pivotal scenes of bubbling green liquid lifted up to hesitant lips belong not to literature but to cartoons and cinema. We never see the transformation whose physical violence I always assumed was central to the plot. We only see the aftermath, and even then we just get glimpses and secondhand reports. The narrative belongs to Mr. Utterson, Dr. Jekyll's lawyer and friend, who is as shut off from the action as the reader. Despite Utterson's Victorian sense of propriety, he fights to break through the wall of mystery that surrounds the doctor in hopes of saving him. Dr. Jekyll is clearly in great decline, and with the checks he has written and the will he has changed, the lawyer suspects his friend is the victim of Hyde's blackmail. Utterson is trying to save Jekyll from Hyde without ever understanding that Jekyll is Hyde. When he finds the truth in a letter after Jekyll's death, it still for a moment seems shocking.

What must it have been like to read this book in 1886 when it was first published? To be for a moment as blind to the outcome as Utterson? Sometimes I think it would be a pleasure to forget what I know, especially when what I know comes from Looney Tunes and is both prejudicial and incorrect. Stevenson keeps the passage from Jekyll to Hyde from his reader's view because this is not a book about violent transformation. It is the story of the darker parts of ourselves, and how without too much exploration there really isn't anything that anyone can do to save us.

I don't have the slightest idea of how "Little Dorrit" ends, but now that the contents of the boxes have been put away and the boxes themselves have been hauled off to recycling, I'm ready to press ahead. I found the book in a canvas bag in the back of a closet, and I plan to start over from the beginning. I'm not sorry about the way things happened: the move, the marriage, the chance to read "Jekyll and Hyde" -- they've all proved to be enrichments to my life. Still, I'm hoping that by the time summer is over I'll have done right by "Little Dorrit" at last.

Shares