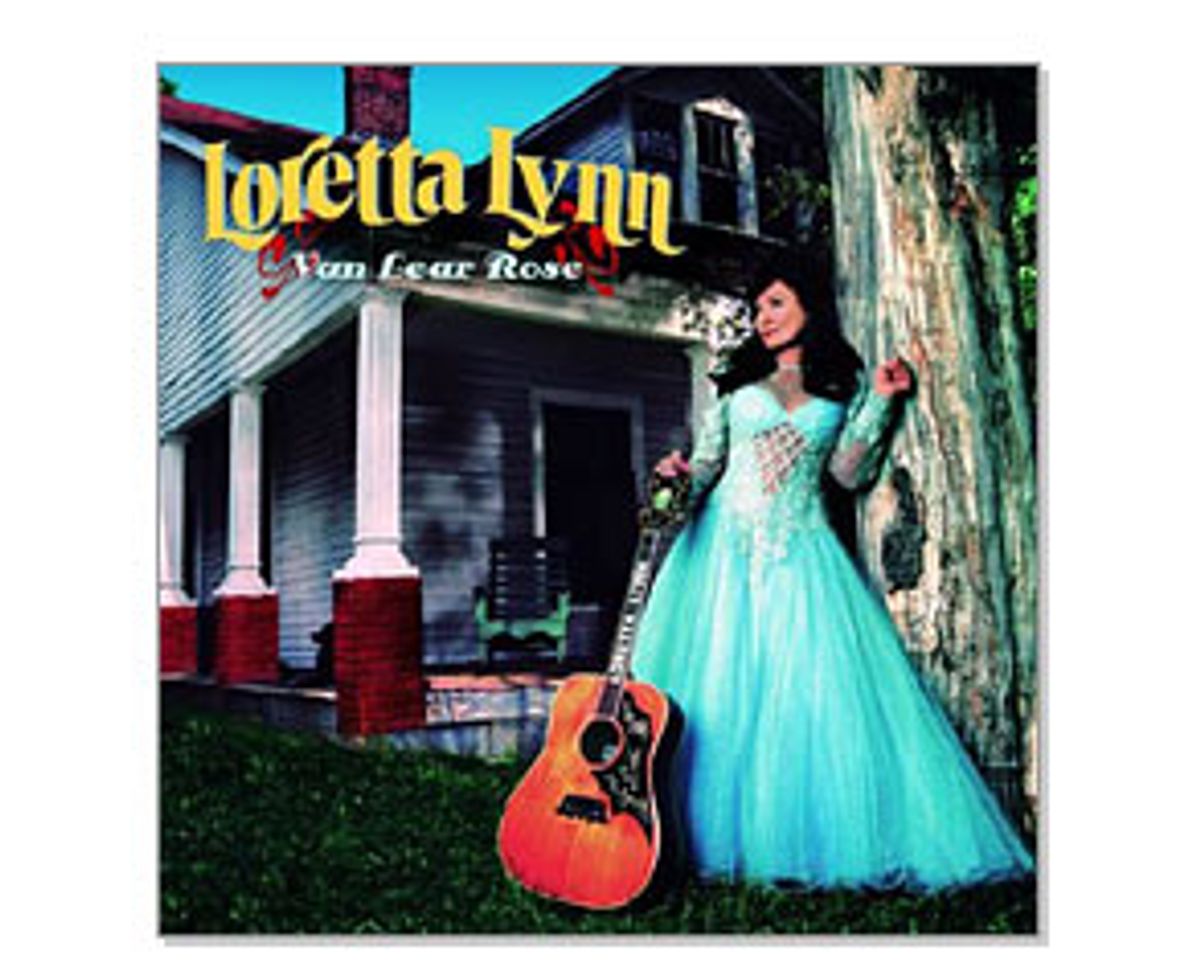

There are plenty of rock, country and pop-music fans who don't believe in God, and I count myself among them. What I want to know, then, is why does the album of the year often arrive just at the time one is feeling lowest? At a time when there's plenty to be depressed about in terms of our political landscape alone, it's even more miraculous that the album of 2004, Loretta Lynn's "Van Lear Rose" is a country album: Country music supposedly promotes conservative values, socially and morally if not politically. (For every Dixie Chicks out there, we also have to reckon with a Sara Evans or a Toby Keith, artists who live by the words "our country right or wrong.")

"Van Lear Rose" doesn't have a political point of view, and, as a work of art, it is within its rights not to have one. But it is, significantly, an album very much of its time. For one thing, Lynn, like Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton before her, is reaching out to a new audience -- a rock 'n' roll one -- that's potentially more appreciative of great country music than many of the people who call themselves country fans are. Like many of her contemporaries, Lynn hasn't had great success on country radio in the past 20 years. But "Van Lear Rose," which was produced and arranged by the White Stripes' Jack White (he also sings and plays on several of the songs, and wrote the music for one of them), is Lynn's way of reaching across the boundaries that have constricted her.

"Van Lear Rose" is a country record, pure and proper, if you believe that country music is more a state of mind than a rigid genre. But even though the arrangements use all the instruments we're accustomed to hearing on a country record (fiddle, pedal steel guitar, dobro and banjo), many of them show an angular inventiveness that's downright startling. This is music that fits squarely within the tradition of country as it's been laid out here on the ground -- the difference is that it stretches up into space, where it's free to blossom into something both familiar-sounding and bracingly new.

These are songs about traditional country-music subjects: the emotional security home and hearth provide; heavy, reckless drinking; the all-knowingness of God; and, of course, cheating -- or, more specifically, being cheated on. (This is Lynn's first album made up completely of songs she wrote herself, with the exception of the brilliantly modulated guitar-and-drum backdrop White wrote for her autobiographical riff "Little Red Shoes.") Lynn's voice has both mellowed and brightened. Maybe now more than ever, its rich contrasts are laid out right up front: It's a voice that's both smooth and radiant -- not just the smoky bourbon you relish at night but the cool OJ you drink the next morning as a restorative.

That voice is showcased to perfection in songs like "Trouble on the Line," which Lynn wrote with her late husband, Oliver "Mooney" Lynn, better known as Doolittle, or "Doo." (Doolittle died in 1996; the couple had been married for 48 years -- she was 13 when they wed -- and raised six children together.) "Trouble on the Line" is the most straightforward of metaphorical country songs, using a lousy telephone connection as a symbol of miscommunication between lovers. Lynn's voice brings these types of conflicts into bold relief, evoking the way talking to someone you love very deeply can sometimes seem as futile and hollow as shouting into a Dixie-cup setup rigged up with a shaky bit of string -- the desolate echo is the same.

You can hear the care and attention White has lavished on the arrangements: Each one is different, and each suits its song perfectly. On the remorseful ballad "Miss Being Mrs." (the title is as self-explanatory as it is clever), he paints a muted but glowing setting for Lynn with a soft, uncluttered acoustic guitar. (Lynn's band here, called the Do Whaters because, as she explains in the liner notes, "They got in there and did whatever we needed them to do," are spirited enough to match her without ever overwhelming her.) On "Have Mercy," White gives her chrysanthemum-fuzz rock-'n'-roll guitars and an insistent drum march that slips into a jazzy break. "Have Mercy" sounds like nothing I've ever heard from Lynn before: With the seductive shiver she puts into certain syllables, and the flirtatious sneer she squiggles on every line, she is the soul of Elvis.

It was Lynn's intention to make a true country record that's nevertheless a very different type of country record. On her Web site she explains to her loyal fans, "This album sounds a little different from my other ones. You've got to have an open mind 'cause some of these songs have a rock 'n' roll sound and the rest are just pure country. I've always thought that a song can bring people together."

But even if Lynn is branching out, she's true to her roots. Songs like "God Makes No Mistakes," in which she explains that God has his reasons for doing things that make no sense to us, have the solid, morally conservative underpinnings that people generally associate with country music. There's something telling, though, in the way that song segues into the death-row ballad "Women's Prison" ("I'm in a women's prison/ With bars all around/ I caught my darlin' cheatin'/ That's when I shot him down"). At the heart of the best country music is the recognition that as imperfect creatures we sometimes do wholly rotten things -- Cash, after all, connected us to the soul of a fellow human being who shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.

People often talk about country music as music that tells stories, and it is. But at its best, it's also literature: We may not approve of Madame Bovary, but Flaubert challenges us not to care for her, and the greatest songs of country music do the same. That's the tradition Lynn is both preserving and expanding here: Playing the part of a wronged wife in "Family Tree," she tells the "other" woman, "I wouldn't dirty my hands on trash like you." The judgmental self-righteousness of the line jumps out at you like a goblin. But if you allow yourself to delve deeper into it, you also hear mournful self-loathing, mixed with heartbroken determination, throbbing underneath.

"Van Lear Rose" has as much sunshine as it does shadow, and its centerpiece is the staggeringly joyous "High on a Mountaintop." "High on a Mountaintop" is a song to play loudly in bad times, a hearty stomp brought to life by violins and tambourines and voices -- not just Lynn's, but those of what I assume to be her backing band, and maybe anybody else who happened to be around the studio at the time. (Whoever these people are, they sing their guts out behind her, in that specific way that session musicians often do -- in other words, imperfectly, but with so much spirit and so many good intentions for staying on pitch, that they achieve something close to a state of grace.)

Lynn, of course, leads the singing, in the kind of voice you can't help but follow. She's telling us about home -- not just her home, but any home, anyplace where we can step back from the madness of the world and reconnect with our very souls. "High on a mountain top/ We live, we love, and we laugh a lot," Lynn sings resolutely with her chorus of workmen behind her -- because although this song seems, on its surface, to be about retreating to somewhere safe, it's really a work song. Contentment, after all, means moving along through life, not hiding from it.

There's lots of tradition built right into "High on a Mountaintop": "Where I come from the mountain flowers grow wild/ The blue grass sways like it's goin' out of style." But the song's freshness makes it feel more modern than tomorrow: It speaks of a comforting continuity, but not of stasis. As I hear it, the subtext of "High on a Mountaintop" is that things are always going to be changing around us, which is why we need to make sure we have a center. This is gospel music for everyone, including atheists. To repeat what Lynn says in those liner notes: "I've always thought that a song can bring people together." Amen to that, Lord have mercy, and please turn it up louder.

Shares