Silvio Berlusconi -- Italy's former prime minister and its wealthiest, most powerful, most flamboyant, most indictable businessman -- often explains the importance of his television empire with an anecdote about William Paley, the founder of CBS. Once, when Berlusconi was sitting in Paley's office in Manhattan, the American asked the Italian to guess the time based on the position of the sun. "That's what a real TV station does," Paley told Berlusconi. "You should be able to turn on your TV and tell what time it is based on what program is on."

Berlusconi, who controls all the private TV networks in Italy and who in fact made his country one of the most TV-addicted nations on the globe, believes Paley's theory reflects nicely on his own place in Italian society: At home, Berlusconi, through television, is as indispensable as the sun. But there's something else about the Paley story that sheds light on the Italian media baron. The Paley anecdote isn't true. The founder of CBS never told Berlusconi that people should be able to tell the time based on what show was on TV. That was Berlusconi's own idea, and he attributes the quote to Paley solely because, as he once explained to his employees, Italians love it when you say that this or that idea comes from an American. "If I had told them it was my idea, they would have said, 'Who does this guy think he is?'" But when Berlusconi explained to people that the thought had come from Paley, "they took it in with their mouths agape."

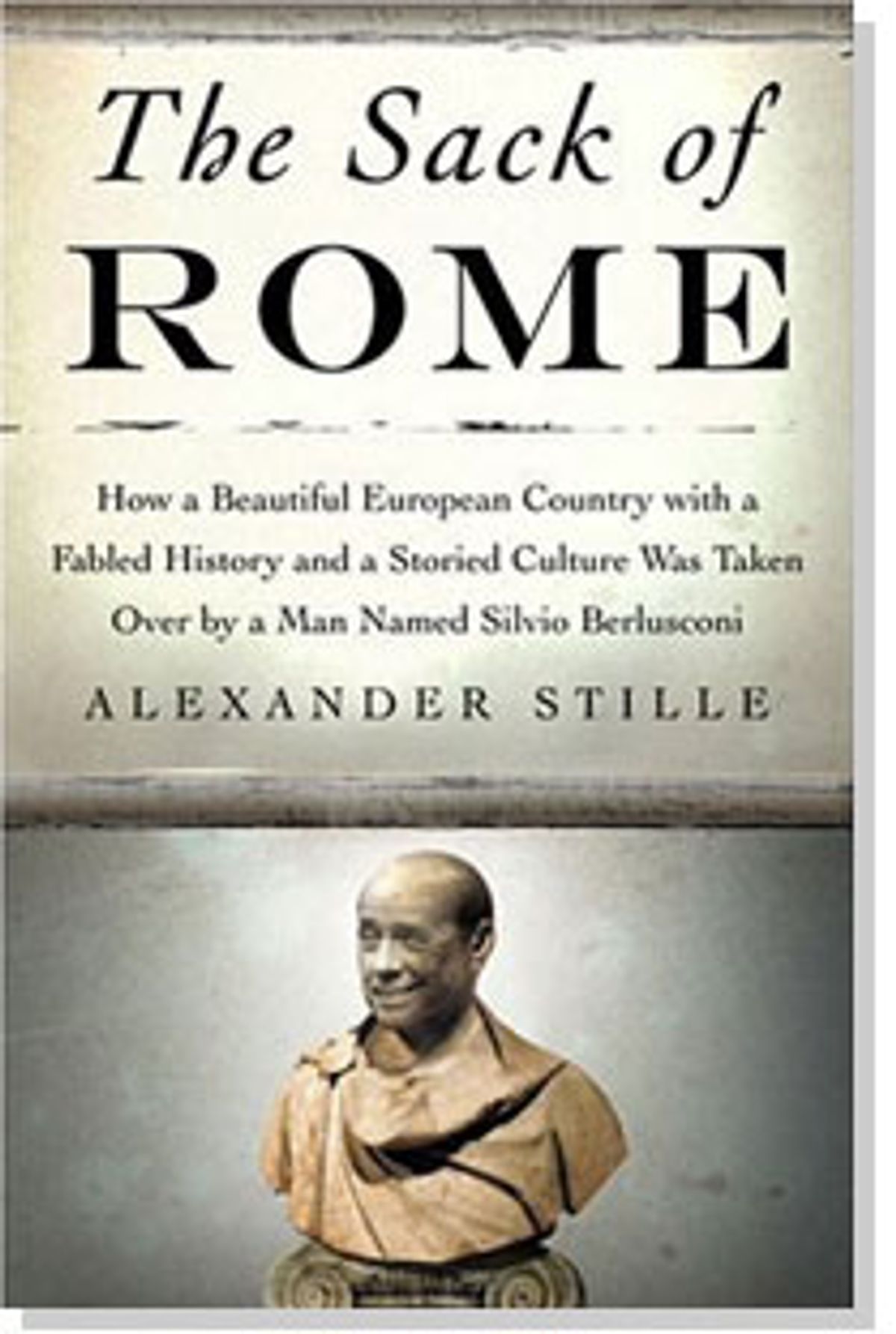

Is Silvio Berlusconi a genius, a master manipulator of television-age politics and business who admirably pulled himself to the top of Italian society? Or is he more like a used-car salesman writ large, a dangerous fellow whose permanent grin distracts you from all the lying, cheating and stealing he's doing in the service of his own wealth and power? "The Sack of Rome," journalist Alexander Stille's new book on Berlusconi, comes down firmly on one side of the question; its subtitle is "How a Beautiful European Country With a Fabled History and a Storied Culture Was Taken Over by a Man Named Silvio Berlusconi." But like any good biographer, Stille is as fascinated as he is repulsed by his subject. Berlusconi is, in Stille's exceptionally well-reported telling, a sleazeball and a crook who ruined Italy. Yet, as the Paley story demonstrates, he's a brilliant, indomitable sleazeball who knows how to get people on his side.

If Stille had given us only the crook, his book might have been as dull as a rap sheet. Instead, "The Sack of Rome" brims with Berlusconi's idiosyncrasies and unmistakable talents. Berlusconi comes off as a formidable salesman, an epic glad-hander who'll do anything (much of it unethical, some of it illegal) and say anything (most of it untrue) to win. On the strength of these skills, if you want to call them that, he has remade Italy in his own image, and to his own ends. He has also made for a thoroughly fun book.

Stille believes Berlusconi's example stands as a cautionary tale for all Western democracies, a sign of what can happen when corporations and wealthy businessmen take over the political process. That's probably true, but, strangely, there's also some reassurance in the tale. It's hard to think of any American figure who wields the sort of power Berlusconi did during his two terms as prime minister. George W. Bush doesn't even come close. Powerful as he is, Bush's control over Congress is indirect, his influence over the judiciary is slight, and he can't do a thing about what the nightly news says about him. Berlusconi, meanwhile, influenced several members of Parliament through his media company (they were his employees), and he kept the judiciary in check through bribes. He also controlled -- and remains in control of -- nearly every major private media outlet in the nation.

"Imagine if Bill Gates of Microsoft were also the owner of the three largest national TV networks and then became president and took over public television as well," Stille writes. "Imagine that he also owned Time Warner, HBO, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Yankees, Aetna insurance, Fidelity Investments and Loews Theaters, and you begin to get an idea of how large a shadow Silvio Berlusconi casts over Italian life." As the press materials that came along with "The Sack of Rome" point out, anyone depressed about the state of American politics can take solace in Berlusconi's reign, as it shows that things "can still get a whole lot worse."

If you think American politicians are born liars, take a look at Berlusconi's relationship with the truth. Though his time in politics has demonstrably aided his businesses and enriched him personally, he maintains that politics has only cost him money, and therefore there's no conflict in his serving as prime minister while owning the nation's TV networks. Despite mountains of evidence attesting otherwise, Berlusconi also says that he doesn't pay bribes, that he's never been involved with the Mafia, and that he doesn't exert political influence over the media he runs. Berlusconi has repeated these lies over and over again until they've become, to him and to many in Italy, tantamount to the truth. Stille recalls once coming out of a three-hour interview with Berlusconi thinking, "I had never before interviewed anyone who had told so many obvious untruths with such enthusiastic conviction." Berlusconi, he writes, "said a host of things that were almost childish in their transparent falsehood ... but he said them with such genuine-seeming passion that I actually began to doubt whether two and two still equaled four."

This is Berlusconi's genius -- by controlling Italy's media, he manages to turn his lies into national truths. "Berlusconi believes that the world revolves around him -- the ultimate narcissistic fantasy -- but he has bent reality to fit his fantasy, so that much of life in Italy does revolve around him," Stille writes. A poll once showed Berlusconi to be the "most loved" figure among young people in Italy. Arnold Schwarzenegger was second. Jesus Christ was third. Can you blame him for believing his own delusions?

In April, Berlusconi was ousted as prime minister in a close election (he left kicking and screaming). As Stille points out, there was ample cause for his defeat. In the years that Berlusconi held office -- his second term, from 2001 to 2006, was the longest reign of any prime minister in Italy's history -- the country's economy grew by just 3.2 percent, less than that of any other country in the European Union. The Italians' standard of living and productivity also plummeted. And the nation loathed Berlusconi's decision to send troops to Iraq. More important than his policy missteps, though, was a national sense of Berlusconi overload. In 2003, a TV show called "Sunday In" asked its viewers to fax and e-mail answers to the question, "Basta con?" What had they had enough of? When the results came in, the show's producers were stunned. Berlusconi topped the list, beating out Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden and high taxes.

In a national referendum held on June 26, Italians rejected a set of constitutional reforms that Berlusconi had favored. His chances of holding on as the leader of the parliamentary opposition now seem slim. Stille cautions that it's never wise to count Berlusconi out, but even if he doesn't survive this fight, Berlusconi will remain enormously influential -- and, besides, his tactics have already been copied elsewhere.

Stille sees Berlusconi's hand in the American right-wing media, where truth often takes a back seat to ideology. Stille also points out that despite American laws against political conflicts of interest, the ties between corporations and politicians in Washington are increasing, not decreasing. In other words, we're moving closer to Berlusconi's Italy. "The Sack of Rome" is an excellent reminder of why that's a very bad idea.

Shares