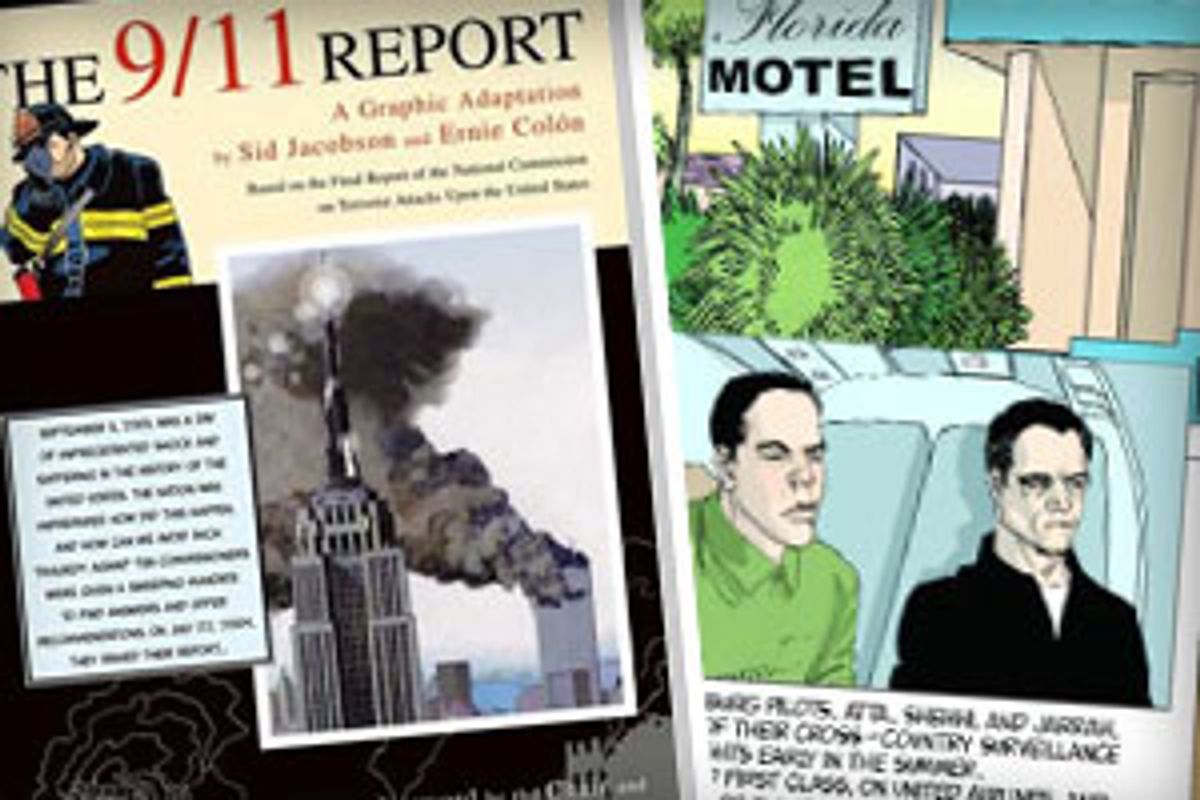

Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón's "graphic adaptation" of the 9/11 Report has the best of intentions. As their preface explains, the idea is "to tell the [National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States'] truly calamitous story so that every person who reads this book will understand what happened and realize all the frightening implications." They note that the commission's original report is rather tough going, and that they hoped to make it easier to follow by turning it into comics.

Sadly, they've failed on that account, producing a garbled mess of a book that leaps frantically and incoherently from factoid to factoid, peppered with made-up scenes that undermine the credibility of the entire affair. It's so poorly put together that the book suggests its creators fundamentally misunderstand how comics communicate information and ideas, and where the line between fact and fancy lies.

It's not as if either Jacobson or Colón is a newcomer to comics. They've been working in the medium and intermittently collaborating for decades -- most famously on "Richie Rich," but also on oddball projects like 1970's race-based comic-strip parody "The Black Comic Book." Colón's angular, stylized line work is pleasingly distinctive no matter what genre he's working in, and he's a fine storyteller when he's got an actual story with a plot to tell, especially if it gives him the chance to communicate subtleties of character with facial expressions.

"The 9/11 Report," unfortunately, fails to play to his strengths, because there's virtually no narrative flow to it -- with very few exceptions, no two consecutive panels show the same characters or are contiguous in time, and Jacobson's script is simply a stripped-down version of the commission's book, preserving most of its structure and lots of chunks of its text. Colón does his best to make the clutter of dates and names and figures look dramatic: On one page, for instance, we see one hijacker flashing a box cutter at another, then two extreme close-ups of a sinister-looking eye.

A lot of the "Report," though, involves head shots and conversations in meeting rooms, and you can tell that Colón was itching to draw something more exciting. A description of the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan mentions that Ahmed Shah Massoud's soldiers "were charged with massacres" -- an excuse for the artist to draw an image of them raiding a village, swinging swords, firing rifles into buildings, blood running in the streets, a peasant woman frantically dashing away with her baby in her arms, some fronds of a tree poking out from behind a building. That panel looks dynamic in a way that no other images in the pages around it do; it also represents a kind of fantasy that has no place in a book like this, because a medium as subjective as comics heads into very dangerous territory when it conflates documented fact with speculation for artistic effect.

A lot of scenes that were evidently grafted into the Jacobson/Colón "Report" to make it more interesting to look at set off the "bogus" alarm, like a panel in which a pair of FBI agents bring in three handcuffed, tattooed, smirking punks, declaring, "Their so-called clubroom was loaded with horse" -- what, have we just stumbled into an episode of "CSI"? (There's no mention of such an event in the commission's report.) Others might well have happened, as when hijacker Khalid al-Midhar is shown hailing a cab at a New York taxi stand. But in a work that claims to be unfiltered, documented nonfiction -- which this book's source material does -- even that kind of seemingly innocuous speculation is irresponsible. It calls into question everything around it: Since we're looking at drawings rather than photos, there's always the possibility that Colón has just made up everything he's drawn in any given panel.

I don't mean to say that it's impossible to make great nonfiction comics about historical events. There are a lot of them: Chester Brown's "Louis Riel," Joe Sacco's "Palestine" and "Safe Area Gorazde," and Art Spiegelman's inevitable "Maus" all come to mind. What all of those books have in common, though, is that they foreground their artists' style -- they're all very personal perspectives on the events they're depicting. The artwork in those books never claims to be anything other than an individual interpretation; the stories directly address the cartoonist's observations in Sacco and Spiegelman's cases, and Brown's storytelling is mannered and stylized enough that the book is obviously his own subjective take on Riel's life.

So where are Jacobson and Colón in this story -- what part do they mean their interpretive spin to play? It's hard to say: They never suggest that their book is anything other than a faithful adaptation of the commission's report and the historical record, and a lot of Colón's images are drawn from photographs (raising the question of why it wouldn't be more appropriate simply to include the photographs in question, if the idea is to turn the report into a visual document). But the authors can't resist throwing in images that they've simply imagined, all by themselves. The commission's report mentions, for instance, that "in September 2000, a source had reported that an individual named Khalid al-Shaykh al-Ballushi was a key lieutenant in al Qaeda." In the comics version, the "source" is a swarthy, jowly, scowling man with a mustache, sitting at an outdoor cafe with a huge slice of cake in front of him, looking over his shoulder and mutttering the information to a lean white man at the table behind him who's graying a bit at the temples and glancing away from his paper -- the perfect spy-movie cliché, and an utter fraud.

When they're not adding their own flights of fancy to the "Report," Jacobson and Colón's version often reads awkwardly -- there's no compelling way to illustrate a lot of this information, so the images can seem vestigial or stagy or redundant. A caption about tracking terrorist financing operations is illustrated with an image of two nondescript men in American military uniforms grimly shaking hands. A page about Osama bin Laden's call for the murder of Americans has a huge photograph of Big Ben in the background. (The only evident connection is that bin Laden's fatwa was published in a London newspaper.) "In Sarasota, Florida, the presidential motorcade was arriving at Emma E. Booker Elementary School," reads one caption; the image that accompanies it is, sure enough, a presidential motorcade driving up to a schoolhouse labeled "Emma E. Booker," with palm trees in front of it.

Jacobson and Colón also make a few attempts to present information diagrammatically -- but, again, Colón's strength is as a storyteller, not a graphic designer. "Nations From Which Bin Laden Has Drawn Terrorists" is an unhelpful half-page image of 21 flags. It's followed by six drawings of U.S. locales to which bin Laden's network extended, all with red dots in the middle of them: "New York" is a map of the state, "Brooklyn" is a map of the borough, and none of the drawings tell us anything that the page's words don't. The one sort-of-useful piece of design in the book is its opening timeline of the four hijacked airplanes, showing how events proceeded in parallel -- although Colón's image of the melee on Flight 93 suggests that it's possible to fit five people abreast into the aisle of a Boeing 767. (Well, this book calls it a 767; as the commission's 9/11 Report notes, Flight 93 was actually a 757.)

There's one other way in which the adaptation is enormously irritating, which is that it's "comic-book-y," in the stereotypical sense of having the excitable, melodramatic tone of a 40-year-old superhero comic book. Every time Jacobson deploys an exclamation point, the book's credibility dies a little. (Caption: "Between August 25 and September 5, all 19 tickets were purchased..." Next caption: "...for September 11!") When the dialogue isn't from documented sources, it tends to be ridiculously stagy, as with Dick Cheney, watching TV: "How the hell could a plane -- Oh, no! A second one!" And the sound effects are genuinely distracting: The collapse of the World Trade Center's south tower, we're told, went "R-RRUMBLE..."

The commission's version of the report was long and detailed for a reason: The story behind what happened on 9/11 is incredibly complicated and not easy to explain, which is probably why Americans were so ready to swallow the lie that it had to do with Saddam Hussein and Iraq. Jacobson and Colón haven't managed to substantially clarify their source, and they haven't magically turned it into an easily comprehensive narrative by dumbing down the text and adding a bunch of pictures. If anything, they've muddied it with misleading visual interpretations. The problem with the comics adaptation isn't that it's a comic book: Cartoonists who were willing to put either more or less of themselves into the project might have turned it into something powerful or at least useful. But this lukewarm hodgepodge does a real disservice to the report and the facts.

Shares