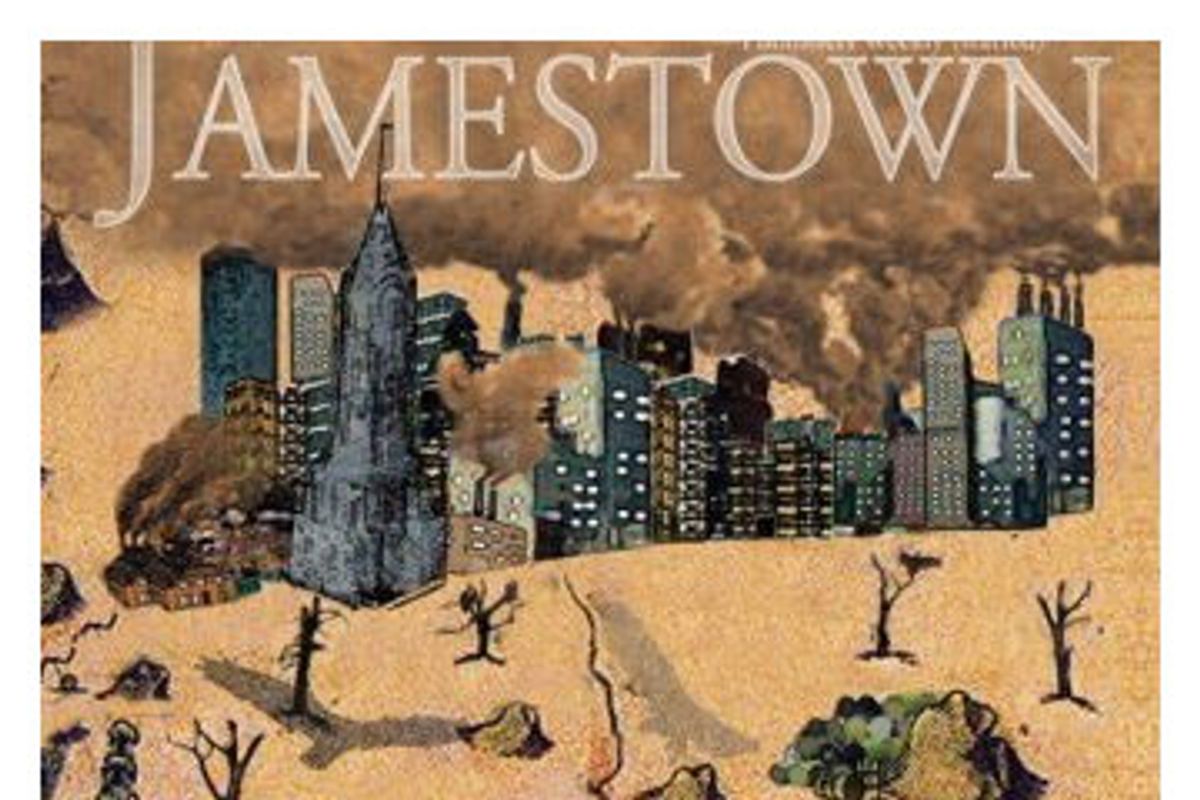

Is the history of America a hopeful tale of fresh beginnings, or the same damn thing all over again? In a way, this question -- whether it's ever really possible to make a better place in the world -- lies at the heart of most of our current political arguments, and Matthew Sharpe's new novel, "Jamestown," takes it down a long, rough road littered with disappointment. A work of hectic brilliance and immense sadness, "Jamestown" is a post-apocalpytic retelling of the settlement of America's first colony. It takes place in the future, but it's also set in the past.

The story begins with the collapse of the Chrysler Building and the departure of an armored bus, stuffed with an unpromising mixture of ex-cons and political appointees, from the embattled island of Manhattan. The expedition has orders to set up an outpost in Virginia and establish relations with the Indian tribes there, with the ultimate end of seizing some of the resources lacking up north -- namely, food, water and fuel. After a catastrophe referred to only as the "annihilation," most of the environment has been transformed into a toxic, Hobbesian wilderness teeming with carnivorous hares and rabid seagulls. "Dreads these days are a dime a dozen and a dozen a day," one of the bus' passengers remarks. The only thing scarier than what's inside the bus is what's outside it.

The novel's two main narrators are John Rolfe, a depressed romantic, and Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, the chief of the dominant tribe in Virginia. In many aspects -- from the sealed box containing the list of the expedition's leaders, to the ascendancy of a shrewd but rebellious redhead named John Smith, to the death of a colonist by torture at the hands of some Indian women -- the events in the plot mirror those of the founding of the original Jamestown 400 years ago. Several of the characters share names with historical figures, from the bus driver, Chris Newport, to the president of Manhattan, James Stuart, and his rival, Philip Habsburg, the ruler of Brooklyn.

In "Jamestown," however, people communicate with wireless devices and film commercials in the ruins of Central Park. Acid rain falls on the forests where Pocahontas' people hunt and her father is attended by Dr. Sidney Feingold, a psychiatrist whom the colonists think is called Sit Knee Find Gold. Feingold administers Rorschach tests to the newcomers, ostensibly as a preliminary to signing some kind of treaty, but most likely just another Indian prank, like giving the colonists bad water and pretending not to speak English ("a ruse my people think both necessary and hilarious"). The supremely clueless colonists, like the original Jamestown settlers, can barely keep themselves alive, and then only with halfhearted help from the locals. "It's true, our English is different from yours," a visiting Indian remarks on touring their fort. "For instance, we wouldn't call that a gate, we'd call it the place where you gave up working on the fence."

Whether Indian or New Yorker, the characters in "Jamestown" fall into two basic categories: those who lament the brutality, injustice and brevity of life and those who intend to be more brutal and unjust than everybody else in order to live longer. The Indians are not Native American by blood, but rather a group that has adopted Native "folkways ... though we know them only in fragments." They've eliminated private property, but like their namesakes, live in a state of unceasing territorial warfare; one of Pocahontas' suitors has a severed hand, a battle trophy from a nearby town, braided into his hair.

None of this suits the frisky, insubordinate Pocahontas, who, as devoted as she is to her dad, wishes the tribe's menfolk would do more in the way of governance than "jog up the street every month or so to kill, rape, kidnap and pillage." The colonists aren't much better, but she still manages to fall for Rolfe, despite his being, in her words, "sworn to anemia as a philosophical world view and way of life." Hers is the most vivid voice in the book, an unpredictable font of astute observation ("he's like a figure in a bad painting who wishes it was in a better painting") and trippy, but winning joie de vivre ("Hospitality, as you may know, is an intoxication of the senses"). She's the fading strain of a playful flute in a symphony otherwise heavy on solemn bass violins.

Despite its doomy view of humanity's chances of making something halfway decent of itself, "Jamestown" careens along, powered by Sharpe's voltaic prose and rich in half-submerged literary allusions. Characters -- especially Pocahontas -- slip in and out of lines from Wallace Stevens poems, hip-hop lyrics, even a speech from Fannie Hurst's sudsy 1934 bestseller, "Imitation of Life." They reenact scenes from "Richard III" and "King Lear." This feels less like postmodern patchwork than like a Western version of samsara, a vast cycle not only of events but also of words, in which the same ghastly elements return again and again. Against it all stands the spirit of Pocahontas, who in the end has just one question for her paramour: "What do you propose to do?"

Shares