Among the many daily pleasures of working on the Internet is the chance to feast upon fresh cuts from the abattoir of the strange, the unfortunate, the tragic, the uncanny, the unintentionally hilarious and often the very unpleasant. I'm talking about wacky news -- those incredible stories that fly through one's constellation of social networks, proving that the world's gone mad, that apocalypse is nigh.

You know what I mean: Old ladies are hoarding cats, their apartments overflowing with precisely detailed amounts of feces. Love sours, and women chop off their lovers' penises. Lusty female teachers everywhere are bedding their male charges. Oral-sex parties, meanwhile, are a fad bigger than slap bracelets in the 1980s. It piles on, this barrage of the bizarre -- judges fiddling with penis pumps, holiday shoppers on stampede, funerals erupting into brawls -- and in the crush, some days, the stories even seem to form a kind of culture, ridiculous and connected and sublime.

If there is a national steward of this culture, it is Drew Curtis, a young Internet entrepreneur in Lexington, Ky., who runs Fark.com, a rollicking daily compendium of strange news. The Web abounds in collections of links to interesting things -- links to interesting things is what the Web mainly is -- but Fark is the most popular and comprehensive such spot for odd news. Every day, Curtis and his team sift through thousands of readers' submitted links, skipping by much of the serious stuff and settling, instead, on stories about sex scandals, odd injuries, animals and other miscellany that, even though it isn't likely to affect your life in any way, is somehow compelling still. Curtis is 34 and married with kids, but his skill lies in his capacity to easily match wits with men half his age (Fark's ethos is very male), and he manages to keep his site cheerfully sarcastic and resplendently puerile. He and his reader-submitters excel especially in writing snappy taglines to news. For example, on Fark a science news article that explains the biological relationship between food consumption and brain size across various species is labeled: "Study shows the bigger your brain, the more energy you consume. This explains how Paris Hilton can survive on a diet of alcohol and semen."

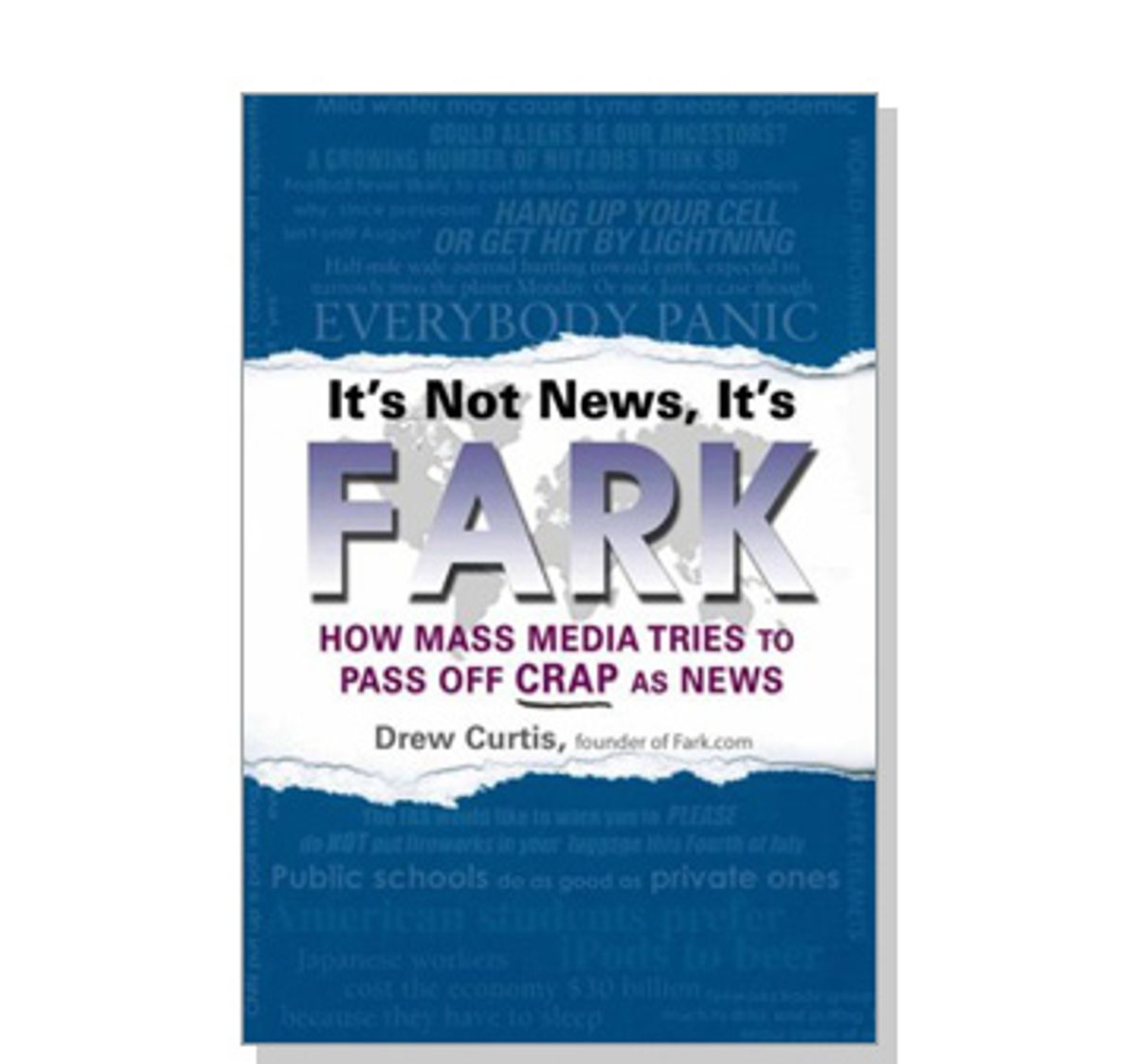

So Fark's a blast, really. Yet Curtis himself seems of two minds about the endeavor. Although he continues to scratch out a decent living from the stuff, he has lately turned against inessential news. In his new book, "It's Not News, It's Fark: How Mass Media Tries to Pass Off Crap as News," Curtis chastises news organizations for running not-real-news news, and he even seems to go after the audience -- his audience -- for indulging in it. It's an odd "bite the hand that feeds you" strategy, like a pastor who holds out the collection plate while mocking the church and the faithful for their piety, and the tone is out of character with Fark.com's generous attitude toward trifling stories. Online, Fark invites readers to revel in the eccentricities of our planet. In his book, Curtis seems to want us to be repulsed by them instead.

The worst part is that Curtis' antagonism spoils much of the fun you might otherwise find in the numerous examples of not-news he has scattered throughout his book. There are some doozies here, but to squeeze them into his larger thesis, Curtis has to spin out all the laughs and convince us, instead, that they should never have been published at all. The Tampa Tribune shouldn't have run the one about the archaeologist who claims the Garden of Eden was once in Florida because obviously the man's a "nutjob," Curtis writes, and "journalists do a disservice to all of us when they allow stories to see the light of day that they know are bogus for the simple purpose of attracting eyeballs." Tennessee TV station WHNT's campus-life investigative piece "Special Report: Friends With Benefits" was similarly unnecessary, Curtis writes, because "it's just flat-out not news that teens who go on dates sometimes have sex." An Orlando Sentinel article discussing the dangers of aviation and fireworks in the summertime -- first line: "Fireworks and flying don't mix" -- is clearly seasonal space filler, Curtis says, because, come on, who doesn't know that?

But there's an obvious problem with Curtis' claim that none of these articles was worthy of publication: When the pieces were published, he posted links to them on Fark, driving tens of thousands of readers their way. And not only did Farkers read the stories, but many also discussed them -- sometimes voluminously -- on Fark's message boards. Granted, many readers made fun, arguing that the people or the ideas in the stories were stupid. But what's wrong with stories about the stupid? The stupid give the smart among us -- or the merely less stupid -- a useful point of comparison, and stupid is also undeniably funny. Here was a news station that had gotten itself twisted up over "friends with benefits." Here was a man who thought Eden could be found in the land of "Girls Gone Wild." "I'm glad crazy is something we can all point and laugh at," one of Curtis' readers wrote in response to that story. "Sometimes I forget what real entertainment is like."

Even Curtis admits the articles, in their ridiculousness, are fun. Of the fireworks-and-flying piece, he writes, "You can almost imagine your local TV anchorperson staring directly at the camera, pointing right at you, and saying earnestly, 'Flying and fireworks don't mix.' And then you fall over laughing."

I'll grant Curtis his point that the journalistic profession is lousy with hacks; this is no concession at all. Facing deadline pressures, facing financial pressures, out of incompetence, sheer laziness and a lack of integrity, the mass media fails often and spectacularly. All the time, reporters put out stories mined from press releases, they engage in easy fear-mongering, they run pointless articles about weather -- and Curtis assembles some fine examples of these.

But I'd argue that many, if not most, of the stories on Fark don't fit this mold. In trying to explain the hold of trivial news, Curtis inflates the influence of the corrupt and the venal, and overlooks something more vital, the power of a good story. A couple of years ago, when a bug-eyed woman named Jennifer Wilbanks ran away from her fiancé, the media went wild over it. Curtis says the story mystified him: "Why the hell this demanded more than a passing media mention is beyond me." Really? A woman so disturbed by her impending marriage she was willing to let her family and entire town believe, for several days, that she might be dead. A woman so far gone she cooked up a wild tale of abduction and sexual abuse to explain her disappearance. Who does this? Our only analogue, indeed, was fiction -- and the reality was even stranger.

What is the deal with those cat ladies? And the teachers who seduce their students -- what were they thinking? (Another situation recently seen in fiction.) We make jokes about the strange-news people -- Lorena Bobbitt, Amy Fisher, Lisa Nowak and her famous diaper -- but the truth is we wonder about them too. Ordinary people who are outwardly normal, just like you and me (though more like you than me, I bet), and suddenly, in a flash, they're in the eye of the world. What happened there, you wonder, and how do I make sure it doesn't happen to me?

Shares