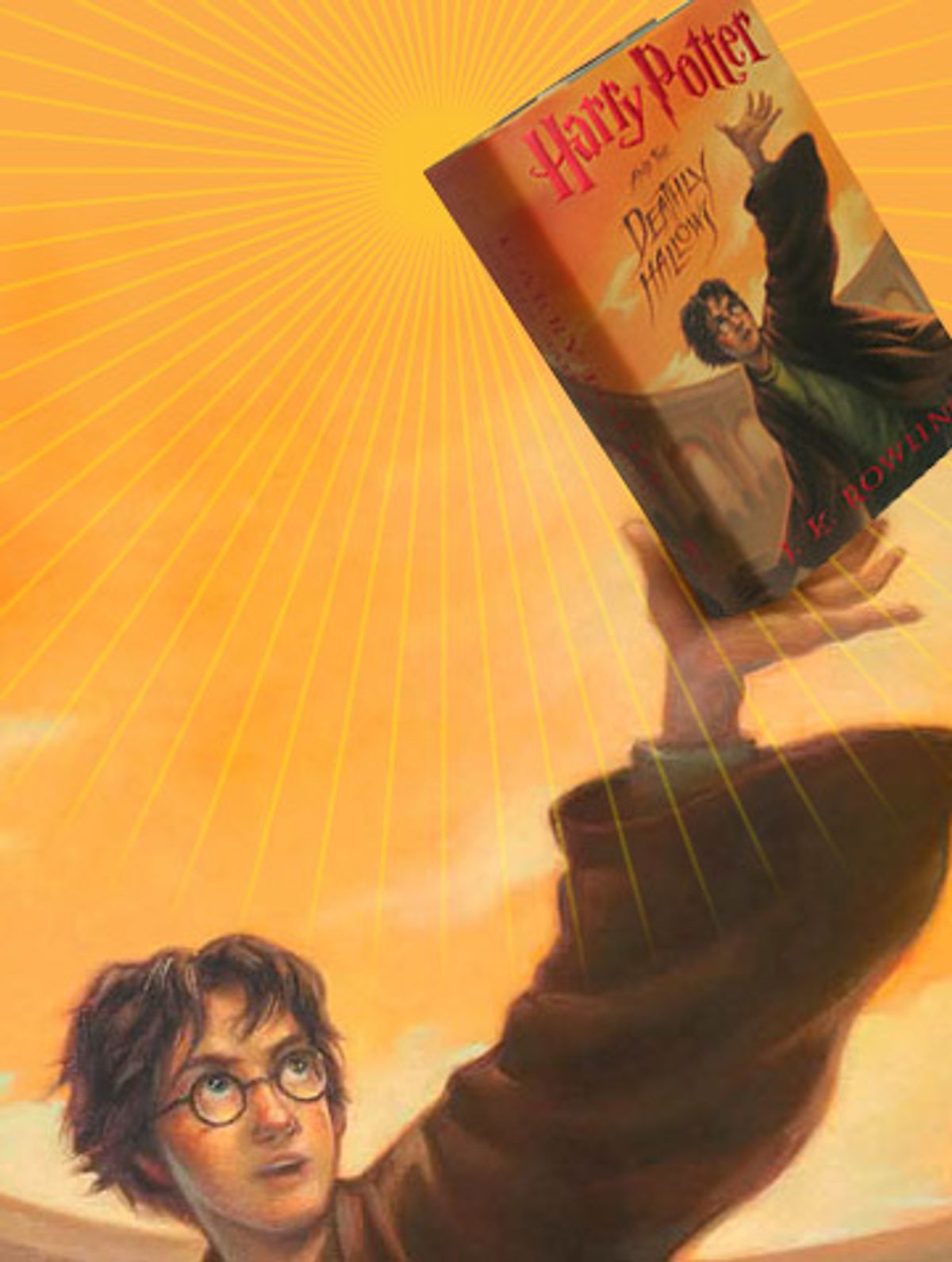

Ask someone what the Harry Potter series is about, and they'll probably answer, "a boy wizard." But in mulling over J.K. Rowling's innovative melding of children's fantasy fiction with old-fashioned boarding school stories, I've concluded that the boarding school element has the edge. Much as we may love Harry, Hermione, Ron, Hagrid and Dumbledore, don't we all love Hogwarts just a little bit more? (Or, let me put it this way: Given the choice between meeting any one of Rowling's characters and getting to attend the celebrated school of witchcraft and wizardry, which do you think most readers would pick?) So brace yourselves, fans: Hardly any of the latest and last book in the series, "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows," takes place at the school.

Whatever the troubles lurking in the richly imagined wizardry world outside its walls, Hogwarts has always been a sanctum for the forces of decency, presided over by headmaster Albus Dumbledore. But, with Dumbledore's death at the end of "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince," Hogwarts can obviously never be the same, and Harry has to be spirited off into hiding by the remaining members of the Order of the Phoenix. The influence of the diabolical Lord Voldemort has grown, infiltrating the press and finally the Ministry of Magic itself. A Nazi-like racialist campaign to "register" and control Muggle-born and "blood traitor" wizards burgeons. Harry, Hermione (a Muggle born) and Ron never get to climb aboard the Hogwarts Express for their seventh and final term.

Of course, the idea that boarding school offers shelter from the rough injustices of the real world is a delusion enjoyed only by people who have never attended one. British writers as diverse as C.S. Lewis and George Orwell have tried to disabuse the general public of its bizarre affection for such institutions and the genre of children's fiction set in them. Lewis was fond of saying that "school stories" fostered fantasies far more pernicious than any fairy tale because they actually tricked children into believing that boarding school offered something more than "raw and sordid ugliness." The writer Neil Gaiman has called Rowling's depiction of boarding school a "weird and idealized" vision of something that's "really all about bullying, torture and [in deference to any children who might be reading this, let's just say that the last word he mentioned refers to an activity usually practiced alone]."

Nevertheless, in the Harry Potter universe, Hogwarts has been the last holdout of the good and true, and by exiling Harry, Hermione and Ron from its grounds, Rowling is forcing her narrative to grow up. Harry has that experience so common to people who've just lost a parent (or, in this case, a parent figure): discovering that the Dumbledore he thought he knew so well had a past he never suspected, one that doesn't fit with the memories he cherishes. The protection spell that his mother cast over the Dursleys' house on Privet Drive expires when he turns 17, and he's got to leave it and them forever; much as he hated the place, he's cast doubly adrift.

Harry and his friends are thrust into a perilous society where the brutality of real-world boarding schools prevails. The omnipresent dread, the held breath at the closing noose of fascism, familiar from so many World War II stories, hovers over the whole book. Much of "The Deathly Hallows" reads like a thriller, beginning with a breathless broomstick chase in the fourth chapter. After a brief, amusing pause for a wizard wedding (no less exhausting than the Muggle kind), it evolves into an extended chase, with Harry and his comrades falling into the clutches of Voldemort's Death Eaters only to escape by the skin of their teeth at least a half dozen times.

These action scenes are expertly executed, and if Rowling really does decide to write more fiction set in Harry's world, she could probably do worse than inventing a wizard detective or spy as her next hero. Unlike those of some great children's authors (Kenneth Grahame, Lewis or E. Nesbit, for three), her prose style has never been especially graceful or beautiful (one Salon reader really hit the nail on the head by calling her writing "sturdy"), but it's perfectly suited to this kind of scene, and her control over the whole novel feels much firmer and tighter than it did in the preceding two volumes, "Order of the Phoenix" and "Half-Blood Prince." She does have to resort once more to the Pensieve (a sort of magical VCR for other people's memories) to handle some heavily expository flashbacks toward the book's conclusion, but by then you're so caught up in the narrative you don't mind.

As for the ending, and the strange, widespread and literarily autistic obsession with who does and doesn't die in it, suffice to say that some sympathetic characters are killed and that everything -- the configuration of the horcruxes, the true colors of Severus Snape, the final confrontation between Harry and Voldemort -- turns out in the only way it possibly could if you thought about it for more than two seconds. But that doesn't detract from the cumulative power of Rowling's storytelling, because a real story, as anyone with half a soul knows, is much more than a series of plot points. Even though (as a grown-up) I did occasionally weary of Rowling's rudimentary romantic comedy and love-conquers-all moral -- and even though I found myself conscientiously ticking off her borrowings from a host of other fantasy classics -- I was still genuinely moved at the end. (Which, by the way, had already been spoiled for me.)

But far be it from me to ruin the book for anyone whose enjoyment of it can be so ruined. This is all I have to say to those readers who have yet to finish "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows": Click on the link below only if you want to read a discussion of the series that includes information up to and including the very last page of the very last Harry Potter novel.

Rowling's gift has always been for boisterous, jolly ensemble scenes and for cooking up zany and prankish magical creatures, spells and devices -- there's as much Fred and George Weasley in her as there is Hermione Granger. From Bertie Botts Every Flavor Beans to the gnomes in the Weasleys' garden to the Whomping Willow, the texture and color of her imaginary world is earthy (but not lusty), homely, grounded, irreverent, antic, perfectly suited to the audience of 10-year-olds she first devised it for 10 years ago. Her voice, tone and imagination are rooted in social comedy and observation, not in the metaphysical and transcendent, which is why her more realistic bad guys -- the loathsome Dolores Umbridge, who makes a most-welcome cameo appearance in "Deathly Hallows" -- are more vigorous and chilling than her supreme antagonist, Voldemort. Umbridge is a bureaucrat, a petty tyrant and semi-closeted sadist allowed to run amok in a wizarding world gone wrong. We've all met people just like her, even if they don't come equipped with enchanted torture pens. Voldemort, by contrast, is a melodrama villain, a device. Sauron, he ain't.

Some critics have objected to an Op-Ed the British novelist A.S. Byatt wrote for the New York Times in 2003, in which she complained that Rowling's books lack the "shiver of awe" she expects from superior fantasy. But you don't have to dismiss Harry Potter the way Byatt does to recognize that she has a point. The sublime is missing from Rowling's series, but then you won't find it in "Barchester Towers" or "A Confederacy of Dunces," either, which doesn't make them anything less than masterly novels. The sublime and the comic don't mix well, and to try to squeeze both into a children's book is the kind of experiment even a master potion-concocter like Severus Snape would wisely avoid.

Nevertheless, for the final, climactic confrontation in a seven-volume series that has become a cultural phenomenon, people expect something epic, momentous, archetypal. So it's no surprise that the closer Rowling gets to that confrontation, the more heavily she relies on borrowings from writers with a natural gift for that sort of thing: Tolkien, Lewis, even Philip Pullman. The locket horcrux that weighs down whoever wears it, sapping their initiative and hope, is one of the more obvious quotes from "The Lord of the Rings," along with the thunderous last-minute arrival of centaur troops at the Battle of Hogwarts (the Ride of Rohan redux). Above all, reading the emotional turning point of the "The Deathly Hallows" -- Harry's solemn walk to the Death Eaters' camp, his willing surrender to Voldemort and the taunting, capering glee of the evil wizard and his minions -- induces (in me, at least) an LSD-grade flashback to the sacrifice scene in "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe."

None of this is meant as a detraction -- the writers Rowling borrows from in turn gleaned parts of their fiction from even older works. The fantasy genre at its best draws from stories older than written language itself; originality isn't really the point. You could even say that Lewis and Tolkien didn't write novels at all (they called their fiction "fairy tales" or "romance," citing much earlier literary forms). Myth, archetype, allegory -- all of these are literary modes in which characters, places and objects often stand not for anything in the real world, but for elements of the human psyche, parts of the self. That "shiver of awe" Byatt wrote about happens when you feel the boundaries between the inner and outer worlds dissolve, if only for a moment. Given that this isn't the register that Rowling usually works in, it's impressive how well she pulls it off when she has to.

But Rowling is most definitely a novelist; she writes about people and stuff, not about elemental forces and unconscious urges. Like all true novelists, she is the champion of the specific and the domestic, the often unsung pleasures and perils of a good lunch, a crush, a ball game with friends and a little gossip about machinations at the ministry -- which is why the doings at Hogwarts and in the Weasley household were always the best parts of the series. Her books, for all their spells and incantations and magical creatures, have never been the stuff that dreams are made of. Instead, they're the stuff that life is made of.

That's why Harry's great reward isn't something otherworldly, like Frodo Baggins sailing into immortality with the elves in the Uttermost West. He gets married, settles down with a good woman and has a few kids. His fate is to make many return visits to platform nine and three-quarters, even if he never again boards the Hogwarts Express. He gets to feel that twinge, that "little bereavement" that every parent feels on his child's first day of school; time passing, life going on. It's a very ordinary, unheroic sort of feeling, and that, more even than the assurance of the book's final sentence, tells us that all really is well.

Shares