When you first glance at writer/artist Eric Shanower's graphic novel series "Age of Bronze," it's hard to guess when it was drawn. It's actually a current work in progress, but Shanower's a classicist, in several senses. His meticulous, fine-lined pen-and-ink work owes a lot to the nearly photo-realist cartooning of the 1940s and '50s, and to the minutely rendered textures and details of early-20th-century book illustration. The subject of "Age of Bronze," though, is literally classical: It's an enormous, all-inclusive history of the Trojan War, the decade-long conflict between the Achaeans and the residents of Troy that's inspired countless artworks over the last few thousand years.

For an event as thoroughly chronicled as it is, the Trojan War is still relatively mysterious: There's no extant ancient document that presents its entire narrative. The war may or may not have actually taken place, in fact; from the judgment of Paris to the Trojan Horse, it's only known to us through legends stacked atop legends, beginning with Homer's "Iliad" and continuing through the movie "Troy" and beyond. So the classification on the spine of "Age of Bronze: Betrayal Part 1," the third and most recent collection of Shanower's roughly thrice-annual black-and-white comic book, is "Historical Fiction/Mythology." That's a clever contradiction: Is it a recounting of something that didn't happen, or an invention to dramatize something that did?

It's sort of both. Shanower's first smart idea was to treat every extant work related to the Trojan War as a potential part of his story -- the "Iliad" and other classical Greek literature, of course, but also Shakespeare's "Troilus and Cressida" and its medieval sources, Mozart's "Idomeneo," C.P. Cafavy's poems about Achilles, even ABBA's "Cassandra" and the movie "Troy." The proliferating versions of the war's history are often incompatible, of course, and sometimes Shanower's interpretations of key incidents synthesize multiple sources. (Was Philoktetes' foot injured by an arrow or a snake? As far as "Age of Bronze" is concerned, both.) Piecing together the historical and mythological fragments into a coherent plot could be a dry exercise, but the passions and rages of Shanower's Greeks and Trojans roar like a charging army of spearmen.

In some sense, "Age of Bronze" is art about art about art, so Shanower's second masterstroke was to brace it against historical ground. He's working from the assumption that the Trojan War happened in the late Bronze Age, roughly the 13th century B.C., and he's exhaustively researched the archaeological record of that era to reconstruct the way buildings, ships, clothing, weapons and everything else looked. ("Age of Bronze" has the longest, most scholarly bibliography you'll ever see attached to a graphic novel.) His settings and characters look less imagined than carefully observed; this is as close as anyone can come to showing what a war in that time and place would have looked like.

Shanower's been working on "Age of Bronze" for 12 years now, longer than the war itself, and he claims he's about a third of the way through it. "Betrayal Part 1" is the third volume of seven -- or, rather, the first part of the third volume. (The earlier volumes, "A Thousand Ships" and "Sacrifice," are both entirely self-contained; "Betrayal Part 2" is probably a few years away.) A new reader would be wise to start at the beginning of the series, especially since the new volume doesn't just begin in medias res, as Horace wrote of Homer, but in the middle of dozens of plot threads. If you only know the story through a high-school reading of the "Iliad," the business with the wooden horse is still a long way off: "Betrayal Part 1" ends just as the Achaeans are about to land at Troy after Odysseus and Menelaus' failed embassy to King Priam. Achilles is itching to lead the attack, Helen is reeling from the revelation of her mother's suicide, Laodike has just hooked up with Akamas, Pandarus is playing go-between for Troilus and Cressida, and Kassandra is raving in horror at her visions of what's to come.

There's much more happening, too, since Shanower's choreographing an enormous cast. (The two-page genealogical chart at the back of this volume helpfully bolds the names of 42 major characters in its pages.) Still, there's one very large and deliberate omission from the legends of the Trojan War in "Age of Bronze": He treats it entirely as a story of individual human interactions, so we never see the Greek gods in action. They may be influencing events or they may not -- the wind does indeed shift after Iphigenia is sacrificed, for instance. But what matters is that the characters believe in them and act accordingly, although Shanower always suggests a secular possibility for the way things turn out. Kalchas, the turncoat Trojan priest, is one of the central characters in this volume: nervous, shifty and perpetually clearing his throat, he's able to manipulate events in enormous and terrible ways, because he claims he's got no choice but to communicate what the gods want.

For the most part, the language Shanower uses is understated, solemn and poetic. Menelaus' speech to Priam, for instance, has the cadence of translated Greek drama: "But the man who commits shameful acts, who upsets order and outrages law, though one day he holds wealth and power, the next he plunges into black death." "Age of Bronze," though, is most of all a visual story -- the earliest iteration of the Trojan War story may be traditionally attributed to a blind poet, but there's plenty to look at, even beyond the occasional spectacles of warships and sword fights.

Some of the most dramatic sequences in "Betrayal" are carried almost entirely by Shanower's artwork. The climactic scene, in which Paris, Helen and her abandoned husband Menelaus confront one another in the court of Priam, is presented as a series of close-ups of the three characters' faces: Menelaus overcome with longing but trying to present his emotional demands as moral imperatives, Paris cocky and openly mocking him, Helen quietly struggling with her feelings and flinching like a 1920s silent-film idol or a '50s romance-comics heroine. And, after Helen rejects Menelaus, there's a magnificently staged sequence in which Odysseus steps forward to address the Trojans, pauses for a moment to close his eyes and compose himself, and then explodes in calculated rage -- spittle flying from his mouth, shock lines surrounding his head.

Shanower's greatest gift as a cartoonist is his command of his characters' facial expressions and body language; he often lets the way his characters look and move around one another say much more than he puts into their dialogue. Achilles' mother, Thetis, is an imposing presence, but she's also faintly ridiculous, prone to scenery-chewing gestures. Odysseus is squat and bearded, perpetually on the alert and thinking five steps ahead, and happy to keep to himself until it's time for him to do something clever. Many of the Trojan War's legends are about love so intense that it destroys everything around it, and when Shanower draws lovers in each other's presence, the force of their erotic attraction crackles from the page. Achilles and Patroklus, silhouetted by the sun (as Achilles recalls the prophecy that Apollo would bring about his doom), are a classic pain-and-comfort duo; Paris can't keep his hands off Helen for two minutes, and Helen knows perfectly well what bad news he is but can't control her lust for him either.

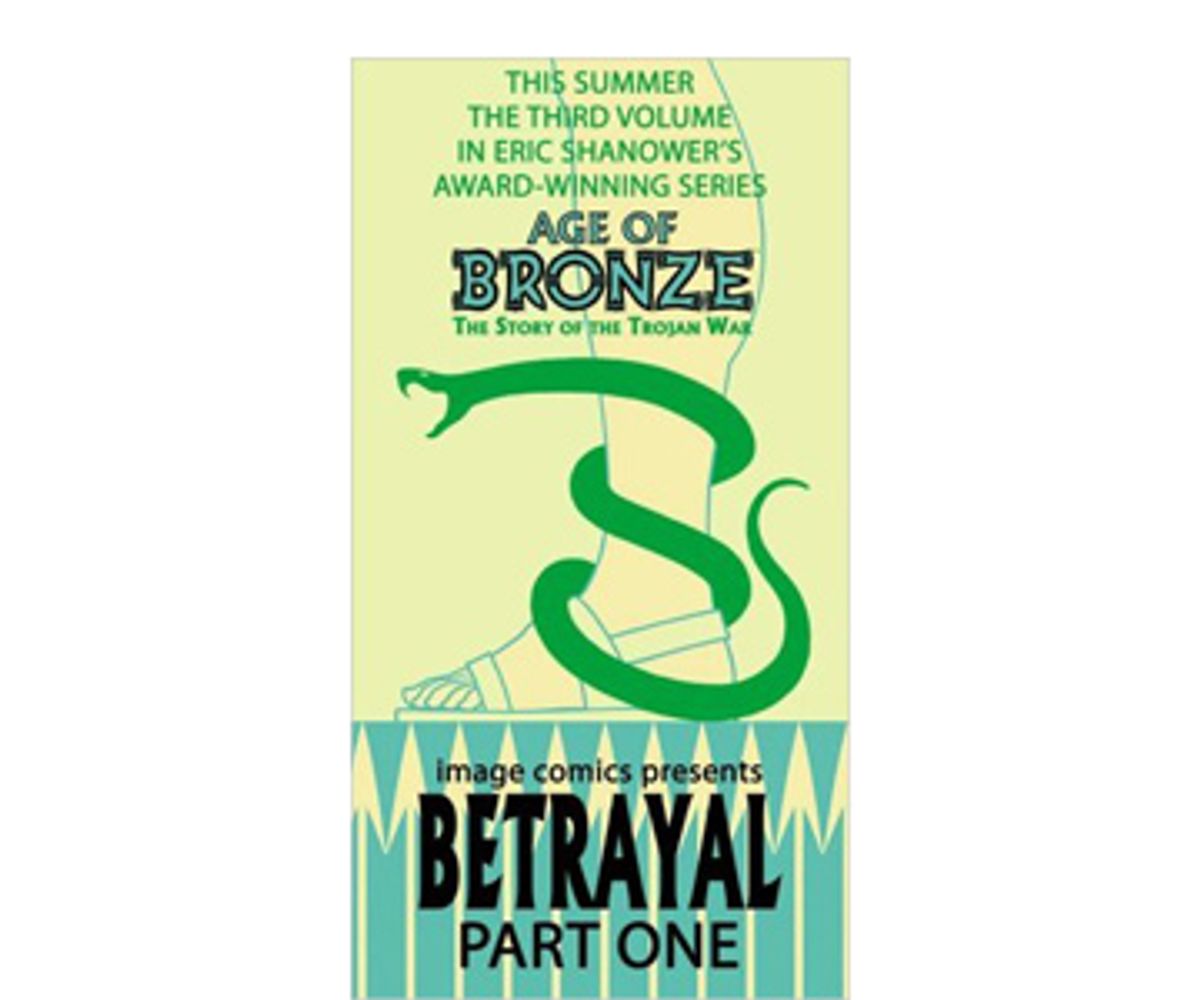

There's a slightly static quality to some of Shanower's figure drawing, which works in its favor here: Many of his characters' poses are (or might have been) copped from pottery, friezes or half-peeled-away paintings. (Before "Age of Bronze," his biggest body of work was a series of graphic novels set in L. Frank Baum's Land of Oz, which similarly built on the archaisms readers expect from those stories.) Other elements of Shanower's classicism -- especially his sense of design and composition -- are virtues in modern cartooning as much as they were in the pre-comics era. "Betrayal's" cover image of a snake coiled around a sandaled foot refers to the story of Philoktetes and more obliquely to the rest of this volume's plot; it's pure and simple enough that it might have been seen on an urn made a few thousand years ago.

Shanower doesn't try to give the Trojan War more contemporary relevance than the archetypal resonance it's always had, and his visual approach is, perhaps, unfashionably un-radical. At a time when the best-known art-cartoonists are leading with their formal innovations, his most expressive gestures come in the form of distinctly old-school craft: rendering, shading, staging, pacing. But if there's a story that every art-maker in the Western world is entitled to embellish, it's this one, and Shanower's treatment of it is gripping to read and beautiful to look at, a feast of images fit for the gods that he's carved away from it.

Shares