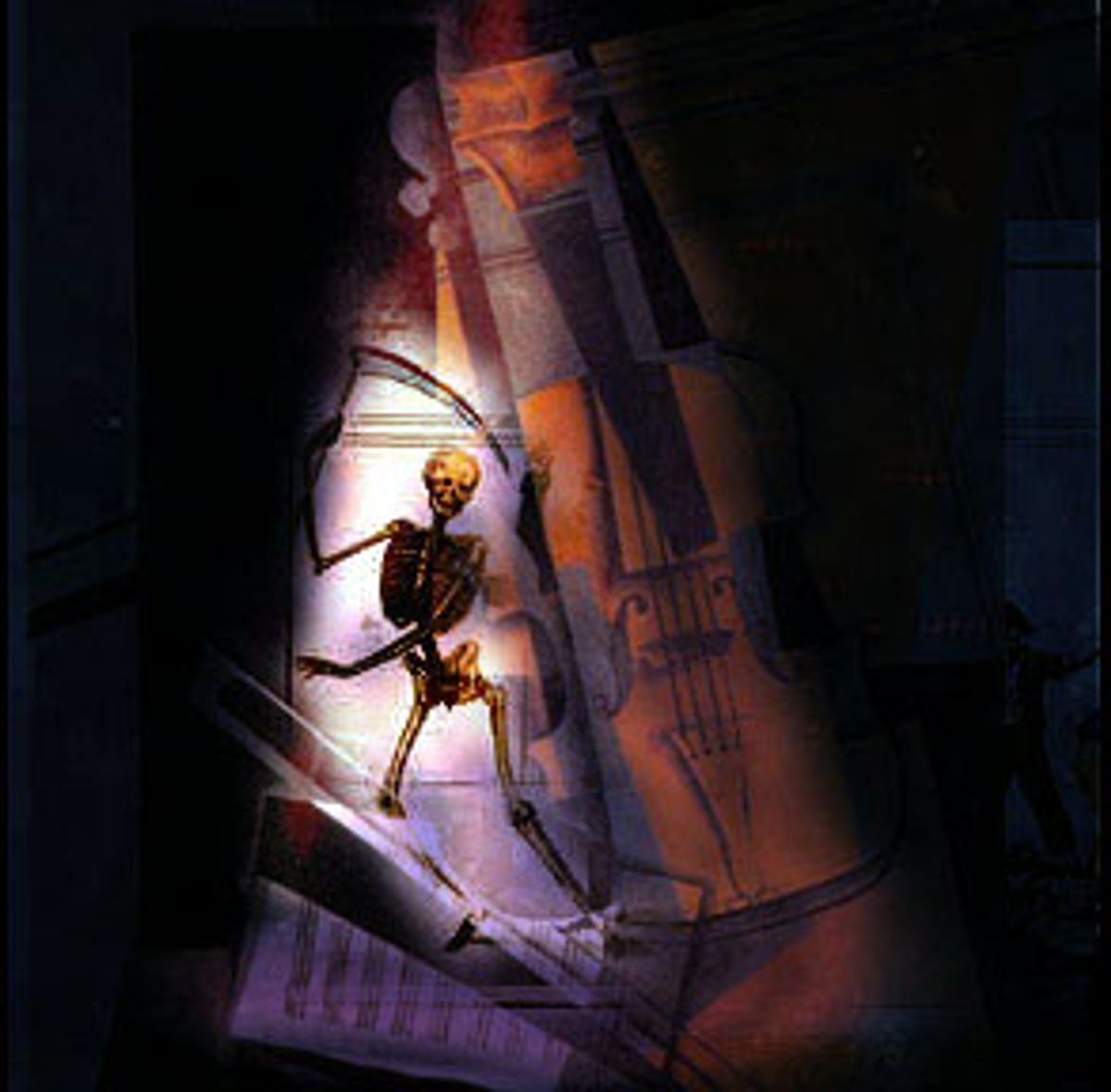

If recruiting for composers were done in the want ads, nobody in their right mind would sign up.

WANTED: Contemporary "classical" music composers. Preparation should ideally begin before age 7. At least 15 years of eye-straining, backbreaking, unpaid or even costly efforts will eventually be met with, at best, hostility or, more likely, with indifference. Financial prospects vary from nonexistent (in many cases negative) to mediocre. Only one out of several thousand applicants need even dream of a subsistence income from their music. Potential bonus: A small percentage of applicants may be offered greater financial security in return for training future postulants in a well-organized and highly successful structure similar to that of a pyramid scheme.

Yet in spite of the seeming irrationality of the choice, an unending stream of young men and women consecrate themselves to writing a sort of music that they know from the outset will never be popular, for an audience that does not want what they have to offer. Maybe it's like what they say about cigarettes: Unsuspecting youths are lured in before the age of rationality. Or maybe all kinds of lies and false promises are made. In any case, this curious situation deserves closer scrutiny.

There are lots of discussions in the world of "serious," "classical" or "concert" music (whatever you want to call it) about the so-called rupture between composers and audiences. Much of the writing about this rupture falls into the following seven broad categories:

1) Composers attacking audiences for not making the personal investment necessary to "understanding" their art.

2) Critics bemoaning the inaccessibility of today's composers.

3) Critics lauding one or another newly arrived "revolutionary" composer, whose revolution usually consists of using the classical instrumentarium to produce works that sound like pale imitations of popular music, or like something a particularly hopeless student of Brahms might have come up with. (Pandering is considered both positive and progressive in this context. It's like lauding as revolutionary a sex therapist who advocates "rediscovering the missionary position.")

4) "Serious" critics beseeching listeners to make the personal investment that the composers mentioned in Category 1 just berated them for not having made up until now.

5) Pessimistic pieces about the future of "classical" music, usually citing the poor demographics for season-ticket holders or donations to major musical organizations.

6) Optimistic pieces hailing some organization or composer's marketing efforts that seem, at least temporarily, to have successfully hoodwinked some sought-after market segment (usually young concertgoers). In the saddest version of this story, part of the ever diminishing resources dedicated to culture are expended on a multimillionaire rock star performing pop tunes with orchestral accompaniment in a so-called effort to reach new audiences. (Perhaps this outreach is effective in winning some orchestra patrons over to pop music.)

7) The ever popular "human interest" profile, apparently meant to convince us that if the composer is likable, hating the music is somehow petty.

While potentially interesting, none of those approaches gets to the heart of the matter. I would venture that the real issue at hand is not the music itself and that therefore no stylistic discussion -- no matter how intellectually probing or unabashedly populist -- will address the underlying subject: the position of art in contemporary society. Now, talking about art is almost as hard as talking about music (which is essentially impossible). But we can't address either the reasons that composers are drawn to writing this type of music or the reasons that audiences reject contemporary works (or are totally indifferent to them) without confronting the A-word head-on.

By focusing on the blame game -- is it the fault of the composers or the audiences? -- we ignore a fundamental difference between what composers think they're offering and what audiences think they're getting, or think they should be getting. Traditionally, most composers have held a deeply felt, almost religious belief in "Art." I know I do. This is what leads us to the profession despite the unpleasantly poor hourly wage it brings most of us.

We believe that if through determination, hard work and talent, we are able to make truly great works of art, sooner or later people will grapple with these works, come to see their value, and develop the sense of awe we feel in the presence of true masterpieces.

This is not to say many composers are certain that they themselves are writing masterpieces. The belief has more to do with the possibility of masterpieces and a confidence that such works will inevitably, even if belatedly, be recognized. Ultimately, we share what some may view as an embarrassingly corny and idealistic view of art: We believe it enriches the world, whether or not the world knows or cares. This belief depends on the idea of intrinsic value.

Faith in the value of art depends on a second, less obvious, premise, just as most religions' beliefs in a divine creator are predicated on a belief in an immaterial human soul. To believe in art, one has to believe in abstract criteria of worth or value. This notion, which is profoundly out of fashion today, has formed the underpinning of artistic endeavor in the West for a long time.

Here's what I mean: A great work is still great even if fashion or society or the cultural institutions of the time reject it entirely. There are essential qualities in the form, shape, phrasing, ideas and a million other harder-to-isolate elements of the piece that, when combined, will ultimately determine the worth of the art object -- its greatness or lack thereof.

Franz Kafka died virtually unknown, a total failure. But he was a great writer even before his work was discovered by posterity. A Rembrandt hanging in the forest would still be great, even if no one ever got to see it. Partisans in the "culture wars" of the 1980s and early '90s tried to attack these notions, but that battle mixed up the issue of what should be in the canon of great art with the question of whether there should be a canon at all.

If one believes in the intrinsic value of art, then -- contrary to most contemporary ways of thinking -- taste and social construction are of decidedly secondary importance. Composers often speak of pieces being well constructed or clever, sometimes even brilliant, and then go on to say that they don't particularly care for them. This is because personal preference is seen as being much less important and enduring than these other, harder-to-define criteria. Even real Shakespeare-haters are unlikely to criticize the quality of his verse. We can all feel the genius even if we are not all sensitive to its charms (or at least this is what I tell myself).

Some composers may be bristling at this point and muttering that they are not so cavalier as to completely disregard public taste and societal demand. They may believe this, but ultimately they are wrong. If taste and society were their real yardstick, then the Billboard Hot 100 would be the true arbiter of worth and value (in the non-economic sense, as it already is in the economic sense). Let's face it, any "classical" composer holding that view is in the wrong business.

This is not to say (as some have done) that success is incompatible with cultural value. It is merely to say that the worth of a work is either intrinsic to it and therefore completely independent of its commercial success (as I believe), or it's determined entirely by its social reception, in which case any flash-in-the-pan boy band is "better" than just about any "classical" composer.

So while an individual composer may feel he is considering both his audience and posterity, the work will ultimately be valued on its intrinsic merits alone. Whether they were achieved in an effort to please audiences or provoke them will become irrelevant.

When we look at our system of cultural production and delivery, we realize that it was shaped by this belief in the intrinsic value of art. Museum curators, artistic directors, ministers of culture, music directors and other chattering-class nabobs exist to sift through the masses of mediocre work and find those with real quality. This is almost the inverse of the pop-music or market-oriented system, where music is played for demographically sorted focus groups, and -- presuming the sampling techniques are adequate -- it's immediately obvious what's a hit and what's a flop.

Over the last few decades, however, even the most revered cultural institutions have been affected by market-think. Selling art these days requires a marketable theme, a marquee name, sex appeal and advertising sponsorships. Most major symphony orchestras now give their marketing directors the equivalent of veto power over the music directors. Album covers of new releases by classical soloists offer a panoply of beefcake and cheesecake. The Web site for talented young violinist Hilary Hahn looks as if it might be publicizing a new show on the WB about a beautiful teen violinist and her struggle to balance the rigors of art and worldwide touring with teenage life. (I want credit if that actually becomes a series.)

Anyone looking at those photos and the seasons now offered by classical music institutions has to wonder whether those involved are still listening for the next great performer who will transform how we hear, or whether they're just looking for a strapless gown or a bad attitude. Of course, this sort of thing exists all over the cultural world. Does anyone believe that the Guggenheim Museum's exhibits on motorcycles or Armani fashions are driven by anyone's conception of intrinsic value?

This situation is the inevitable result of an unwillingness on the part of the public to take someone else's word -- the word of an "expert" -- on whether something is worth seeing or hearing. Today we want to decide for ourselves. "Choice" is the buzzword of our times; how can one object to it without seeming to be some sort of arch-reactionary snob who wants to force his taste on others? But there's the rub: The whole market-driven system is predicated on a basic belief incompatible with the idea of intrinsic value or worth.

Technology magazines predict a day when we will shape a movie as it unfolds, giving it the ending we want, concentrating on the characters that interest us most, and generally making it into a movie designed for each viewer. How wonderful: We'll all be the artists shaping our own artistic experience.

Marcel Duchamp and John Cage taught us that a toilet seat or traffic noise could be appreciated aesthetically. So why not shape sculpture into what we want to see, or a piece of music into exactly what we want to hear? If we accept the market's basic assumption -- that the customer is always right -- then this can only be a positive development. My fear, however, is that rather than free the artist in everyone we may be eliminating the place for art altogether.

What happens if there are truly intrinsic values, or if we at least believe that there are? This view, which has dominated our culture until quite recently, led schools to force children to read Shakespeare and college students to read James Joyce. The idea was that whether they enjoyed these works or not, the works were somehow important.

Even in the United States (one of the few countries that do not see the need for a cabinet-level guardian of culture), presidents invited orchestras to play for them whether or not they liked orchestral music. John F. Kennedy had an aide who told him when to clap so as not to embarrass himself. Families dragged children to operas, museums and ballets.

Furthermore, the idea of intrinsic value was by no means limited to "high culture." Guys tried to impress their dates by taking them to jazz clubs instead of going to hear a Bee Gees cover band. Rock fans who aimed at sophistication sought out more ambitious "underground" music and were quick to display their highly developed tastes to their friends. Liking the most popular or accessible group was often seen as a sign of superficiality. Generally people felt that if they got nothing out of "difficult" art or literature, the problem was likely their own. After enough time, some and perhaps even many people made it over the hurdles and came to love it, whether "it" was John Donne or Richard Wagner or John Coltrane.

On the other hand, what happens if there are no intrinsic values, or if people act as if there were none? Then it's a waste of time to grapple with much of anything. People will need to have a wide menu of choices. If something doesn't satisfy them, they'll flick to another channel, and if there's nothing good on any channel, the search itself becomes the program. The father of the current U.S. president was known to prefer the Beach Boys to the Philharmonic and saw no need to pretend a love for high culture: If he didn't like broccoli, he just wouldn't eat it.

The lesson that has been taken from Cage and Duchamp is that if traffic noise and toilet seats are equal to Mozart and Rembrandt then so are Garth Brooks and black-velvet Elvis paintings. This view quickly leads to taste being the only legitimate arbiter. In the cultural realm this rapidly leads to the downward homogenization of taste toward the least common denominator, a phenomenon that makes almost everyone vaguely uncomfortable.

But even in a techno-utopian future where content on demand lets each person's taste be perfectly satisfied -- those who like Schoenberg and those who like Billy Ray Cyrus -- there may not be any place left for art. Art is not about giving people what they want. It's about giving them something they don't know they want. It's about submitting to someone else's vision. This is hardly ever discussed these days.

The lesson I take from Cage and Duchamp is not that all art is equal, but that all art demands that we surrender our vision to the artist's. Duchamp dares us to see the beauty he found in the toilet seat. Cage tries to force us to turn the same ears to traffic noise as we would lend to Mozart. They both know that art is a team effort between artist and audience and that the latter half of that pair needs help in understanding the importance and nature of its role. This is not to say that either Cage or Duchamp is a great artist, necessarily, but that they both understood how difficult it is to engage with art.

Some of us, even in this day and age, may have waded through "Finnegans Wake" or "Remembrance of Things Past," but how many would go through works of that difficulty if we suspected that in all likelihood they were just complex crap (as is inevitably the case with new art)?

That's what I said: Most art is crap. This may be a shocking idea to many people. We think of art as the great masterworks we know, and it's very easy to forget the mountains of mediocrity that were sifted to lift Bach or Dante or Emily Dickinson to their Olympian heights. I have heard people suggest that somehow the gene pool has been diluted to the point that no more Beethovens are possible (this suggestion actually came from a composer). What they forget is that Gioacchino Rossini was arguably more famous than Beethoven in the early 19th century and that a French opera composer named Giacomo Meyerbeer was much more popular than his rival, Richard Wagner.

In almost any era, the sheer mass of bad or mediocre work tends to dwarf the good or great works. This can lead us to assume that the past was somehow better, since we kept only the best parts and threw out the crap. I would venture to say that there have probably been more masterpieces created during the past 20 years than there were in the last 20 years of the 19th century (an easy bet, since the population is so much bigger now). We just haven't finished sorting the gems from the garbage yet.

Imagine having to go through a collection of the10 million paintings -- probably a low estimate -- done last year by everyone from famous artists to unknown talents to my grandmother (who recently started painting as a retirement hobby). Even if you knew there was a new Picasso in there somewhere, which of course you wouldn't, how would you keep your eyes fresh enough to see it? And once you stopped believing that there was anything all that special to be found, why would you bother?

If no one is willing make this effort, most great new works will never be found at all. Difficult works, like those of Joyce or Proust (or Schoenberg or Messiaen) will become all but impossible to discover, and perhaps also to produce as well.

This was why culture became an undemocratic realm in the first place, and why attempts to democratize it may bear unwanted side effects. To find great art, we need people who are able and willing to go through those 10 million paintings on the off-chance of finding one masterpiece. This screening process means that when you or I decide to spend time on art we can reduce our choices to works that have already been evaluated and recommended. Someone -- presumably someone who has demonstrated knowing more about these things than we do -- thinks they are worth spending time on.

I'm not saying the system was ever perfect. Individual people will always try to advance their friends and punish their enemies. But the pressure not to be left out of an important trend, and the desire to find the next big thing, forced some degree of integrity and openness in even the most corrupt of art administrators. Ultimately, it was in their interest to promote as "great" things that truly were great.

But when the so-called authorities themselves buy in to the idea that nothing is intrinsically worth more than anything else, they become a negative force. They're no longer trying to find great works and expose them to the public; they're just hoping to impose their tastes, promote their political or social agenda, or simply get rich and famous.

I believe the same thing is happening in more popular art forms like jazz or film or some kinds of pop music. Perhaps because these forms don't make quite the same outrageous demands on their listeners and viewers -- and I mean that in the best possible sense -- the process doesn't seem to be as far along. Still, around the world Hollywood movies increasingly dominate the market, driving the various traditions of art cinema to the margins. Jazz, which can require an enormous amount of knowledge to appreciate fully, seems to be fighting for its survival, in constant danger of becoming little more than upscale aural wallpaper. There seem to be fewer and fewer hardcore buffs eager to scour the local clubs for another Coltrane or Miles Davis.

In jazz and rock, the work itself and the performance of it are joined in a way that is quite different from the case in literature or classical music. That relationship may blur some of the distinctions I have been making, but I don't believe it fundamentally alters them. When high school students start broadening their record collections and searching for more adventurous artists they haven't heard before, they do so because they believe that great things are to be found out there. Once that belief disappears, turning on top-40 radio or MTV will be enough.

Real art cannot be an act of manipulation or marketing, but only an act of faith. Faith that great art is something remarkable. Faith that someone, somewhere, sometime might make the effort to understand what an artist has to offer -- and not merely seek what is already known.

Make no mistake, the surrender required by art (even the most accessible art) is hard. Maybe we're no longer willing to make such efforts. There are so many things we could be doing instead. The two hours spent in a concert are two hours we could have been eating a good meal, making love, surfing the Internet or watching TV.

It requires a tremendous leap of faith to surrender control of our perception to someone else, on the off chance that they may offer us something we never knew we wanted but now would not want to be without. If we don't really believe in this possibility anymore -- in the inherent importance and transformative potential of art -- then why would anyone in their right mind take the risk?

Aspiring composers who make the irrational career choice I mentioned at the outset of this article still believe in the power and validity of art (or at least they have suspended their disbelief). If society leaves them no room for that belief, however, they may find that their already marginal position only gets worse. Just as environmentalists came to see that protecting the habitat of endangered species was crucial to saving them -- it wasn't just a question of stopping poachers -- we must realize that the choices we make now about culture and entertainment will determine the future of art.

If we could turn back the history of the human race and run it over again, I'm not sure that anything like the Western artistic tradition would happen twice. It seems like an aberration: a cultural form that serves no obvious function, does not appeal to most of the population, and is so expensive that it can never support itself. Yet this form of expression, which set a tiny handful of individual humans free to pursue their vision without regard to taste, understanding and practicality, has given us an astounding body of work.

One day we might wake up and find that all the young people who dreamed of becoming composers had done the calculation, seen that it was a poorly paid and undervalued profession, and gone into medicine, banking, management consulting or law. It's easy to assume that art has always been with us and always will be, but this is ultimately naïve. The classical repertoire cannot exist in a museum, without a continuing tradition.

As Igor Stravinsky said to Robert Craft in their book of conversations, "The crux of a vital musical society is new music," and this is true of all the arts. Art was the result of specific social conditions. If we eliminate its environment it will die, and no amount of cultural-studies dissertations on Britney Spears or pseudo-intellectual rhetoric about how all expression is equally valid will replace the works that no longer come into being.

In 1802, when his hearing was already beginning to degrade but before he was completely deaf, Beethoven wrote a letter intended for his brothers to read after his death. In this letter, which has come to be called the Heiligenstadt Testament, he bemoans his fate, but asserts his faith in art: "I would have ended my life -- it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me."

That was what pulled me and people like me into composing: the need to bring forth something within us. But what will artists do when everyone is bringing forth and no one is taking in? If artists are willing only to be the artists (or, in contemporary parlance, the content providers) and never the audience, if we as a society cannot give up control in return for a chance at an unexpected insight, if we refuse to take a risk on something new and unfamiliar, then there's no more place for art. What's the sense in being Beethoven if even those who can still hear won't take the trouble to listen?

Shares