Woody Harrelson is ideally cast as Starbuck, the con man in love with his own

con, in the new Broadway revival of N. Richard Nash's "The Rainmaker." He brings

his trademark wised-up bumpkin presence to the role, his mad satyr's grin, his

unmistakable touch of self-parody. Scott Ellis' production for the Roundabout

Theatre Company (which premiered in a limited run at the Williamstown Theatre

Festival last year) is beautifully crafted and deeply pleasurable, but it's

Harrelson who brings it to life.

He needs to, because that's the way the play --

a 1954 hit now best known for the movie version starring Burt Lancaster and

Katharine Hepburn -- is constructed. It's set in a tiny, mid-Depression

Midwestern town whipped by a long drought; the drought is an emblem for the

female protagonist, Lizzie Curry (Jayne Atkinson), who's heading for

spinsterhood. Starbuck appears out of the windless night, claiming implausibly

that he can conjure up a storm for a hundred bucks, and puts an end to both dry

spells.

Nash's play is hokey and homiletic, and there's no music in the lines.

Starbuck corners Lizzie, pointing out the nervousness that, along with her

pragmatic dismissal of his boastfulness, conceals her sexual terror, and you long

for the poetic intensity that Nash's contemporary, Tennessee Williams, could imbue

a similar encounter with in a play like "The Eccentricities of a Nightingale."

Instead you have to settle for the usual brand of Broadway-drama speechmaking as

the characters tell glaringly obvious home truths about each other. They've been

drawn mostly to fulfill functions. Lizzie has a wise, loving father (Jerry

Hardin, in a sweet-natured performance) and two brothers who stand at opposite

ends of the spectrum: the elder, Noah (John Bedford Lloyd), the practical one,

who runs the farm and says things like "Drought's a drought, and a dream's a

dream," and the younger, Jim (the immensely likable David Aaron Baker), who's

driven by his hormones.

Sense-talking Noah continually tries to control Jim -- to

take him down a peg, to harness his youthful wildness -- but Starbuck champions

the boy, just as he fights for Lizzie when Noah tells her to face up to the fact

that she's doomed to be an old maid. Lloyd gives a believable performance in a

bummer of a role -- a man whose confidence in his own eternal rightness sours

everyone's milk. And Ellis gets as much cartoon humor as he can out of the early

scenes between the brothers, playing Lloyd's rangy cowhand looks against Baker's

toad-hopping energy so they're like a squabbling Mutt and Jeff.

Ellis and the actors deserve a lot of credit: Nothing exposes the limitations of Nash's

imagination more than the joshing male exchanges in this play, especially the one

where Lizzie's father and brothers try to entice the laconic deputy sheriff, File

(Randle Mell), into courting her. Mell is suitably sturdy and he has an amiable

low-key humor, but emotionally repressed File, who can't admit his wife ran off

on him, is almost as crummy a part as Noah. (The biggest mistake the play gets

by with is matching him up with Lizzie, whom we love.)

Still, Nash is no fool. The play has an inner spring: When Starbuck connects with Lizzie, firecrackers go off. Hepburn played Lizzie with a breathless lyricism, as if she

were hanging off the edge of the world, and she made a touching joke out of the

character's gawkiness and her rural manners -- and of course there was no other

way she could make us accept the most aristocratic of Yankee actresses in the

role of a back-country spinster.

Atkinson doesn't try to play against

Nash's language -- she grounds the character in it. Big-boned, plainspoken, she

hauls her suitcase wearily across the stage at the top of the play (Lizzie has

just returned from a fruitless trip to visit some eligible young men in a

neighboring town) and you understand exactly who this woman is. When her family

persuades her it's a good idea to invite File home for supper, she puts on a cool

silk dress (Jess Goldstein designed the letter-perfect costumes), but her legs

give her away -- she doesn't walk like a woman who truly believes she looks good

in that dress. Atkinson gets at Lizzie's feelings directly and then, without a

fuss, she crawls inside them. It's a superb piece of acting.

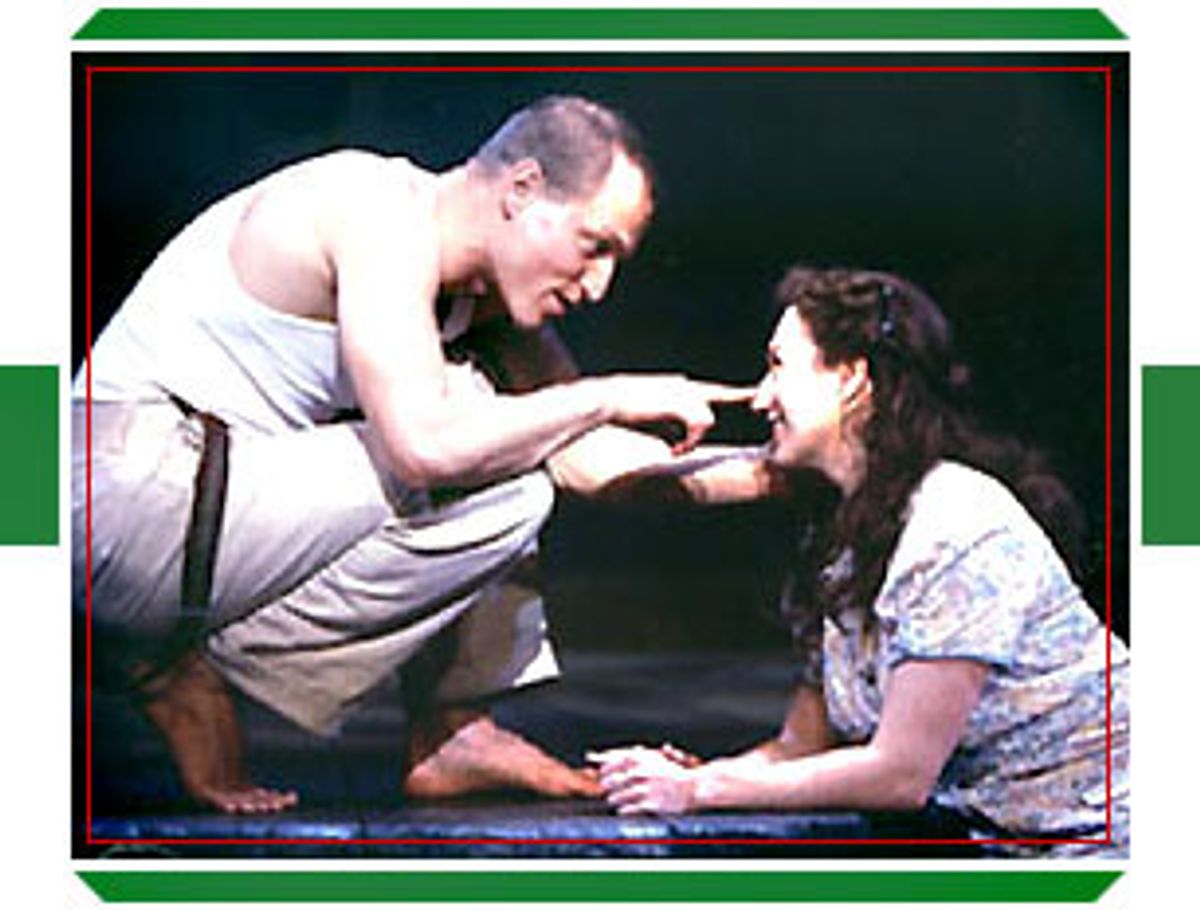

In Act II, Harrelson's Starbuck leads Lizzie downstage center, takes down her hair and

tells her she's pretty, making her repeat it over and over until she believes it,

and with Atkinson it's clear how much she wants it to be true and how scared she is

that it won't be. Hepburn played this climactic moment by making herself beautiful --

by exposing, suddenly, the swan lurking inside the ugly duckling. In

Atkinson's reading the scene is about something else entirely -- about emerging

sexuality, which carries its own tremulous beauty. When Starbuck kisses her she

sinks to her knees, presses her eyes shut and turns away from him as if she were

holding on to a desperate dream.

Harrelson doesn't duplicate the free-flung athleticism Lancaster had in the Starbuck role, and

it takes him a scene to warm up after a rather stiff entrance. But his hound-dog

approach to this character is sensationally effective. He's irresistibly

clownish -- you can see why people are happy to be suckered by him. When he

delivers his big monologue about the first time he made rain, he peeks out of the

corner of his eye to see how Lizzie's taking it -- to check whether he's turning

her on yet. This grinning goof loves his hard sell so much he turns himself on.

Harrelson's bio doesn't list any previous stage work, but he's as charismatic

here as he is on screen, and he and Atkinson work wonderfully together. Nash's

dramaturgy is as square as they come, but the Sunday-matinee audience at the

Brooks Atkinson Theatre responded joyfully to it, as did the audience at

Williamstown when I saw the earlier version. (Except for Harrelson, who replaces

Christopher Meloni, the cast is the same.) This is a canny mounting of a

crowd-pleasing entertainment -- skillfully staged, with a scruffy, rough-hewn

appeal.

"The Rainmaker" is a fable about how faith carves a fairy tale out of the

workaday realities -- Starbuck's vision of Lizzie unmasks her beauty, while her

belief in him transcends his fakery and brings the rain. All three designers --

James Noone did the sets, Peter Kacrowoski the lighting -- balance realism and

stylization to carry that theme. Noone's work is particularly fine: The

unmoving windmill, realist symbol of the long drought, stands below a slightly

fantastical drop with miniature cut-out farmhouses, each one lit up and plunked

down on a broad twist of road like the landscapes in David Hockney's

English-countryside paintings. And Starbuck's and Lizzie's love scene takes

place under a misty white moon that peers out of a huge expanse of sky.

The

characters in "The Rainmaker" discover that they have to live somewhere between

reality and their dreams. Ellis and his collaborators are dreammakers with

their feet on the ground, able to take a banal play such as this

one and release the magic in it.

Shares