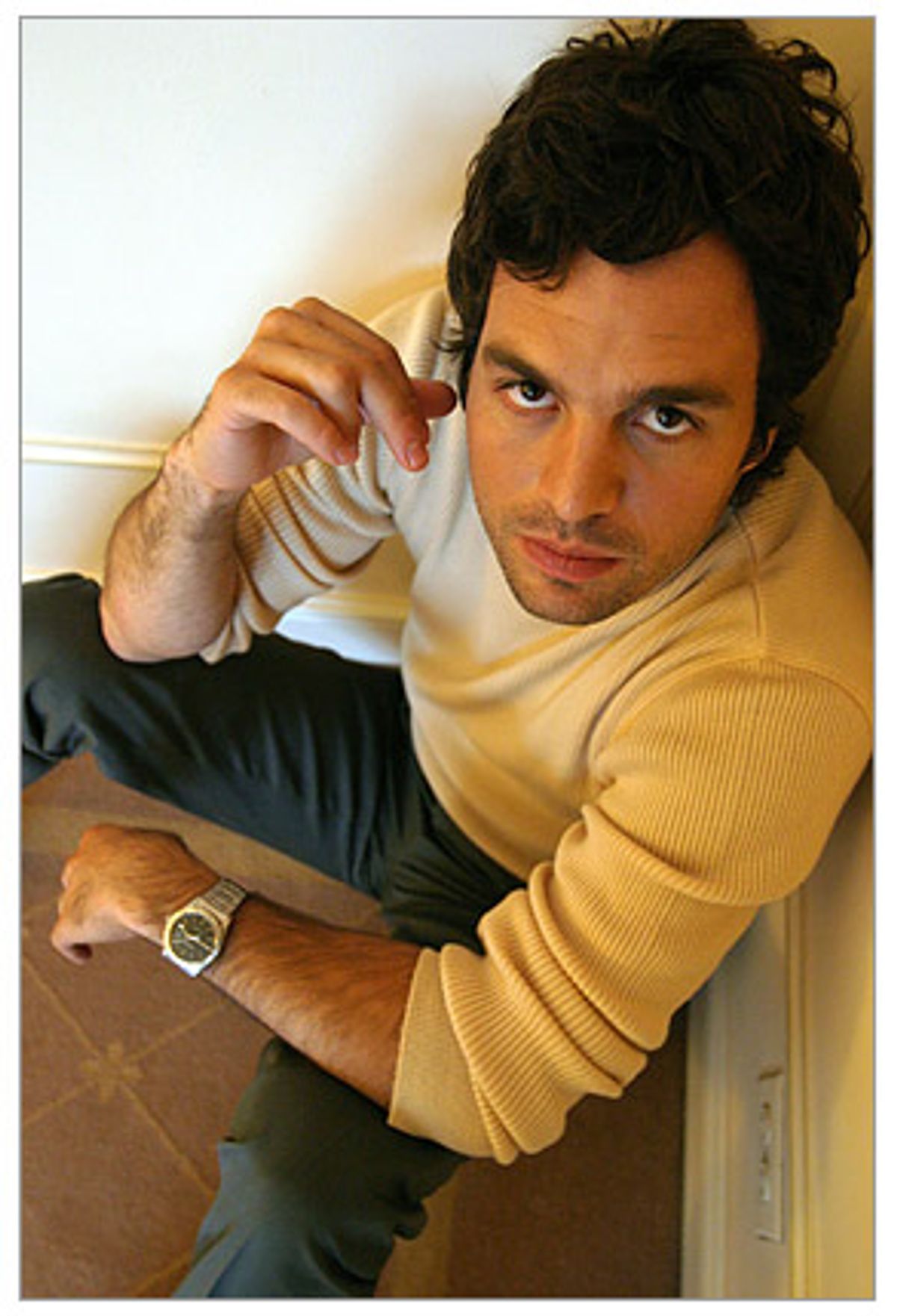

Mark Ruffalo is the thinking woman's sex symbol. Say his name out loud among a gaggle of women or gay men, and watch as their minds turn filthy and their voices get deep and dumb with longing, like a herd of Homer Simpsons drooling over that one delectable doughnut just out of reach. It's been that way since "You Can Count on Me" came out in 2000, when no one could stop talking about Ruffalo, the unknown actor who brought vulnerability and sweetness to the role of Terry, Laura Linney's misguided brother.

Ruffalo's career took off immediately, and he appeared in quick succession with Robert Redford and James Gandolfini in "The Last Castle" (2001) and in John Woo's "Windtalkers" (2001). He was set to appear in M. Night Shyamalan's "Signs" (in the role that went to Joaquin Phoenix), when he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. Ruffalo made a full recovery and returned to work, but the experience changed his outlook forever. It wasn't until Jane Campion cast him in her suspense thriller "In the Cut" (2003) that the silent, lustful majority came out of the closet with their crushes on the low-profile heartthrob. In that movie, Ruffalo plays Meg Ryan's lover, a mustachioed cop who's something of an expert in the bedroom. The film got mixed reviews, but the love scenes were the stuff of instant legend.

This year, Ruffalo, 37, brought new charms to the tech-geek stereotype when he stripped down to his tighty whities with Kirsten Dunst in Charlie Kaufman's "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" (2004). He played Jennifer Garner's dreamy boyfriend in "13 Going on 30" (2004) and also appears with Tom Cruise in Michael Mann's "Collateral," which opens this week.

Will Ruffalo be pigeonholed as an object of lust? His remarkable chops as an actor and good taste in roles should prevent that from happening -- although sex appeal didn't exactly hurt Colin Farrell or Brad Pitt. But then, Ruffalo's appeal lies in those qualities that separate him from his swaggering peers. He seems devoid of that cockiness that keeps Farrell boozing and schmoozing in tabloids or Tom Cruise grinning disingenuously on the talk-show circuit. Far from a cookie-cutter leading man looking for his next blockbuster, Ruffalo remains committed to the small theater company he helped found and to the sorts of low-budget independent films that stars of his caliber usually sidestep for higher-profile jobs.

John Curran's "We Don't Live Here Anymore," an independent film that won rave reviews at Sundance, may be his most challenging yet. Based on two short stories by Andre Dubus (adapted by Larry Gross) the film, which opens nationwide next week, focuses on two couples whose marriages deteriorate as the boundaries between them become blurred. At times excruciatingly dark, the film's unflinching exploration of the battleground of marriage is heavy lifting for any actor, but Ruffalo approaches his role with a mesmerizing mix of fury and vulnerability, and his performance is as nuanced and as heartbreaking as the breakout performance that jumpstarted his career.

Here's more bad news for those already consumed by their adoration for Ruffalo: He's every bit as charming in person as he is on the big screen. During an entire hour-length interview, he leaned forward on the couch and listened attentively, laughed easily, and expressed profound interest in my new puppy, happily recalling the Jack Russell he and his wife used to have that learned how to open the refrigerator on his own. Before the hour was up, he'd offered his thoughts on everything from infidelity to his brush with serious illness and the mentality of your average Hollywood lemming.

I just saw "We Don't Live Here Anymore" last night and I really enjoyed it, but I love movies about dysfunctional relationships, so...

What better kind of movie is there? But this film does it in a way that it's not too alienating. I think people who've had long relationships can kind of see themselves in it, and they see how a relationship gets to a point like that.

Absolutely. You can understand how each character got to where they are.

Yeah. You can see the dreams not realized. Being young parents, there's no money. They [Jack, played by Ruffalo, and Terry, played by Laura Dern] aren't talking to each other, because so much work goes into having young children. You know, they just lost each other along the way somehow.

One nice thing about the movie is that you can't predict how any of the characters is going to react to the situation.

Yeah! See, I know what they're going to do, because I got to read it beforehand!

Well, that helps.

So I don't get to enjoy that aspect of it.

For the rest of us, it's so hard to know how each person will react. Although you never really know how even someone close to you will react to such extreme circumstances. And your character is probably the most conflicted character of the four.

Yeah, they're all pretty conflicted. Hank [played by Peter Krause] is probably the least conflicted in a way. Everything slides off him. But Jack [Ruffalo's character] is at an age where his life dreams aren't being realized, and he sort of feels his youth slipping away, and he's struggling financially. He has questions about whether or not he married the right woman. Is this the life he's meant to have? There's that great Tolstoy excerpt about, "He realized the life he had may have all been a lie." And he's fantasizing about another kind of a life. But at the bottom of it is a decent guy who has a certain kind of morality. And so, when you have a moral character doing immoral things, you've got a lot of conflict. Yeah, I feel bad for Jack. He's in a bad spot.

Do you think that doubting process is almost an arbitrary thing that anyone can experience, or do you think it's specific to Jack's situation?

I think that it's something that happens in this culture and in the culture of marriage -- even a man who does feel like he's had it all or got everything he wanted. You know, they call it the gray itch, or the seven-year itch, or whatever. Obviously 50 percent of our marriages don't work out, so something is happening to people after years and years of being married.

It's interesting though, with Jack. It doesn't seem like it's sexual -- it seems more of an emotional thing.

Yeah. I think he's having a midlife crisis. And it isn't sexual, but it's about the way he feels about himself. He doesn't feel sexy or sexual, and a lot of it is indicative of the breakdown in their communication. They just stopped sort of being with each other. And just years of this sort of unspoken resentment. It's years of "Why is the house so dirty all the time?" or "You know what, honey? I never had my literary career." She's a literary genius, she's really the talent of that couple in the book. And she subjugates her talent to be a mother. So there's an enormous amount of resentment that's built between the two people that's never been expressed and that's created these huge, vast distances between them.

I wonder why they don't make that clear in the movie, that she has that background.

Yeah, I do too. We talked about it.

Maybe it complicates things too much to make three out of four of the main characters literary scholars.

I think so. I think we were touching on it. Some of it got cut out because of length. You know, she asks him one literary reference, but it isn't exactly clear in the film that she doesn't have her dreams fulfilled.

There's something about the way she falls apart that's both familiar and yet so fierce. Your sympathy peaks, at the end, for her. Although when your character tries to talk to the kids about a possible family breakup -- that scene is heartbreaking.

Yeah, it's devastating. And this guy, Jack, is a child of divorce. He knows what that'll do to his children. He does know the cost. It's funny, because he's going along in this kind of cloud, and he's totally unconscious, and then he becomes aware of all the consequences, and not until that moment does he know. He's in a stupor; he's like the walking dead up until that point.

You have a real skill at portraying vulnerability in all of your roles. Where do you think that quality comes from? Have you always been open about expressing your weaknesses?

Uh, no. [Laughs.] I try to hide my weaknesses pretty much across the board. [Reaches for his water.] Do you want some water or anything? [Gets up and brings a bottle of water over.] I don't know. These kinds of characters, if you don't express their vulnerability -- you need to get a key into what kind of a person they are. I think people are generally vulnerable, in some place, if you catch them at the right time. Even when I was young, I just always found it interesting when people were vulnerable. I mean, it's not something I'm really conscious about.

It's just part of what you do naturally.

Yeah, I think people are really complex, and even the most heinous person has some human quality to them. And I'm always interested in getting to those moments. I feel like in film, you get a chance to see someone in their personal life interacting, and then you also get those moments of privacy that really sort of indicate a depth or something that's very opposite from the way they're acting in their lives. And film is the only medium where you get those private moments, that we don't even see. Even the people we love that we spend all of our days with, we don't even get the chance to see them really in a private moment.

That's probably why you leave a movie and feel like, "Why isn't my life that rich?" Because you don't see everything.

No, you don't. Even my wife -- we've been together for seven years. My parents, I've been with them for 37 years. There are things about them that I don't know, still.

You spent eight years in L.A. as a bartender. How does that inform your experience now? Does it make you cynical about the people who you have to deal with at all?

No, but I was really cynical when I was bartending. They used to call me "Bitter Guy," because by the time I was coming to the end of that period, I was really glad to be leaving it -- only because you're dealing with drunks all the time. But, that toughened me up, you know? That was a really important time in my life. I was in some rough-and-tumble bars, and I'm not really a rough-and-tumble guy. So to be in that world and have to be protective and tough was a good learning experience for me. I think it kind of helped me become a man.

Do you think you battled that bitterness in order to get your first big role, or do you think it was just random and the bitterness kind of faded away once you got it?

Ninety percent of my angst as a young man came out of the fact that I wasn't getting any jobs and I wasn't able to do what I do. And I felt like I was really good at it, but no one else seemed to agree with me. So there was a lot of frustration and bitterness and depression and sadness. That was sort of alleviated as I started to work, pretty quickly.

Instantly, probably.

[Laughs.] Yeah, I mean, it was like...

One good review, and it's gone!

Not even the reviews -- I mean, I was doing plays, and I love that, but it was this lemming sort of way of thinking in Los Angeles that no one could do anything without some sort of critical mass. No one here will make a decision unless there's some real ballsy -- I mean, I've been lucky, I've had some really ballsy directors of low-level things that have said, "I don't care who's hot, I want this guy. I think he's the best actor for this." But that kind of thinking is not alive and well in Los Angeles. And that was frustrating to me. Because people who could get me jobs were telling me, "You're the best young actor in Los Angeles." And then they'd say something stupid like, "My hands are tied" or "The studio doesn't want you." And that sort of thing just drove me crazy, because they're telling you how great you are, and at the same time...

Well, there are people who can appreciate your talent, but they're not brave enough or they're not real artists. Because a real artist should have the ability to say, "Goddamn it, this is what I want."

Yes, yes. And that doesn't happen very often here.

But by the same token, you can't just believe that you're another lemming. You have to maintain some hope that your quality will shine through.

Well, that's what you do, for years. I was lucky and got some nice breaks eventually. But for years, some deep part of myself said, "You're great, you have something to offer, just stick with it." And believe me, I've quit acting several times.

On low days, did you ever see that guy Dennis... What's his name? The one with the car that has "Actor for Hire" painted on the side?

[Laughs] Yes. Dennis Woodruff. Yes.

Did you ever think, "Oh my god, I'm just like that guy, I might as well be handing out videos of my acting on the streets"?

No, I was like, I wish I had the balls that that guy has, to be that out there about how great I thought I was.

But then, do you want to be someone's punch line, like when they cast him in "Volcano" and had his car carried away by lava?

Well, yeah, there's a hanging back, because you don't want to become the guy that people make fun of. But this town is filled with people who never got a chance -- really talented people. I mean, I've been in acting classes for six years, and I've seen really talented people who are in one way or the other... My closest friends, still, haven't even scratched the surface, in some ways. But they're not even trying to get big, they're just trying to get work, you know? I still do plays with these guys here...

Tell me about your theater company.

Oh yeah, since we're here. [Laughs.] We're called Page 94. I mean, Page 93.

I was gonna say, isn't it Page 93?

Yeah, it's Page 93. This is literally our tenth title. Over the years we've tried everything.

It was Page 92 for a while...

Yeah, then it was Page 93. We were all fighting over a title, and then someone just picked up a book and opened it to page 93 and said "How about Page 93?" and everyone's like, "Sure! Fuck it! Fine! I gotta get home! Name it whatever you want!" But we've been together for, God, it's been like 16 or 17 years.

Do you worry, when your schedule gets too intense, that you'll lose touch with that aspect of your life?

I haven't been as close to everyone [lately] as I have been, and that's kind of sad. But those people are the closest, that's family to me, so we catch up pretty quickly when we do see each other. I worry about it, but I've been in it long enough now that no one's going anywhere. I have a project, "Sympathy for Delicious," that I want to direct that was written by Chris Thornton, who's part of this group, and I'm gonna do a play with another writer who's part of the group.

When you got sick after "You Can Count on Me," how did your perspective change?

I don't know. That was a real blessing in disguise. But I've talked so much about it... [Laughs.] I'd rather not talk about it. All you need to know is, I'm great now!

OK. I can just link to one of the other interviews where you talk about it.

Yeah, do a link! You can have a long list of links. I've talked a lot about that before. But the overall thing was: Live your life fully and make sure it's your life at the end of it. Don't look back and think, "Oh, I lived my mom's life" or "I lived my agent's life" or "I lived my wife's life." It's never as crisp as the first realization, but it's pretty much woven into who I am now.

So it's something that you don't have to remember to do.

No, it's so galvanizing, and there's so much heat created from it, it sort of re-tempers your whole soul. I used to worry, like, "Will I forget to take this experience with me?" And my friends would say, "You're forever changed. There's no turning back."

That's good, though. Do you see other people and think, "Man, all that guy needs is a hard kick to the groin..."

Yeah, those people, you think, "In 10 years, you'll know." Maybe they're young, they just haven't been through anything yet.

And it's kind of a shame, because before you go through some things, it's tough to appreciate what you have.

That's true. But I didn't either, so I can't blame them. It's hard to get it. You don't really understand it until it happens.

Do you have a strategy for choosing a mix of small and big roles?

Yeah, I mean, I pretty much go where the roles go. There's kind of criteria: First is the role, next would be the overall piece, and then people I get to work with, and then money. But I've been able to sort of step easily between bigger films and smaller films. And I feel like I haven't compromised anything by doing it. I just ask myself, "Have I done this character? Would it be fun to do? Is it speaking to some part of me at this time in my life?" I often find that the really great roles are in smaller pieces.

How hard is it to find those really great, smaller movies?

Well, in the past five years, it's all sort of changing. I mean, even with this film, Warner Independent is taking it out. There's been a huge shift for studios. They find that the public is finding independent films appealing, and there's a market there that can be exploited. So they say, "What are they doing over there, and can we do it in what we do?" And because of financing now, it's very difficult to get a small picture off the ground without a movie star in it, and it used to be that didn't matter so much. And so, the bigger actors are stepping down into the independents, the independents are trying to be bigger and more mainstream, and the studio pictures are seeing what the independents are doing, and making money, and saying, "How do we make our studio picture more character driven and have a better story?" Because people are obviously paying to go see those sorts of things. So there's been in the past five years a real sort of -- the lines have become blurred between a studio picture and an independent now.

So now Spider-Man says quirky things.

[Laughs.] Yeah! Now Spider-Man's an interesting character: He has a darkness and he's conflicted. And I think ultimately it's healthier. It's kind of sad to see the independents losing those more original voices. I get a lot of scripts, and you don't find a script like "You Can Count on Me" or this script too often. I mean it's few and far between now on the independent scene. And usually there were five or six of those floating around at any given time.

Oh, there were more small, quality scripts floating around before?

Yeah, I felt like there were more sort of courageous films being made in the independent world than are being made now.

So fewer people are resigned to staying at that level.

I think so. It was like an outsider's medium, and now it's sort of become a more mainstream medium. Plus, now investors are like, "I want a return!" Instead of saying, "Sure, let's throw the dice, because I love independent cinema and I love small stories!" Instead it's like, "I want a return, what are you talking about? I want to double my money. I want to triple my money." So it's just changed.

Well, it seems like you're well situated in both worlds.

Yes, I've never had so many great opportunities. Who knows how long this will last? But I'm in the best of both worlds right now.

It's nice to be able to choose!

Yes, I have choices! Before it was like, whatever came. I don't have a job yet! But it's scarier. It's all gotten so much more crazy.

Because the stakes are higher.

Yeah, everything's compounded, you know?

How do you remember what your goals are, and make sure you're still guided by the right principles?

Material. It's all material.

Oh, I thought for a minute you meant material wealth!

Ah yes, material wealth! It's all numbers. I just do some number crunching, that's all. I've got a really great accountant!

No, no. A lot of the people I work with trust me. They're like, "Hey, you've done really well by following your own compass, so keep doing it." And I've been doing this long enough that I think I can recognize good material pretty well now.

Shares