Given David LaChapelle's hipper-than-thou status as a sought-after fashion photographer and music video director, I expected "Rize" to be an exercise in visual wankery, each shot designed and tweaked and art-directed to within an inch of its life. LaChapelle's exploration of "krumping," a new form of dancing that's becoming popular in South Central L.A., was sure to be an extended display of style over substance, an ultra-cool look at another empty trend that no one outside of New York and L.A. will ever care about.

But by the first few minutes of "Rize," it became clear not only that LaChapelle, 37, was a natural filmmaker, but also that he had far more heart and soul than I had anticipated. "Rize" focuses on a new, frenetic dance, and although the film is visually awe-inspiring, it goes far beyond the tale of just another trend. The breathtaking, animated, at times even aggressive movements you see these kids perform are a bold expression of the pain and suffering they've experienced living in a place where drugs, gun violence and hopelessness can crush the dreams of even the most optimistic. LaChapelle knows which moments matter, from funny exchanges between the dancers to their moving first-person testimonies. Ultimately, "Rize" speaks not only to the importance of community but also to the fundamental need for self-expression, particularly in the face of adversity.

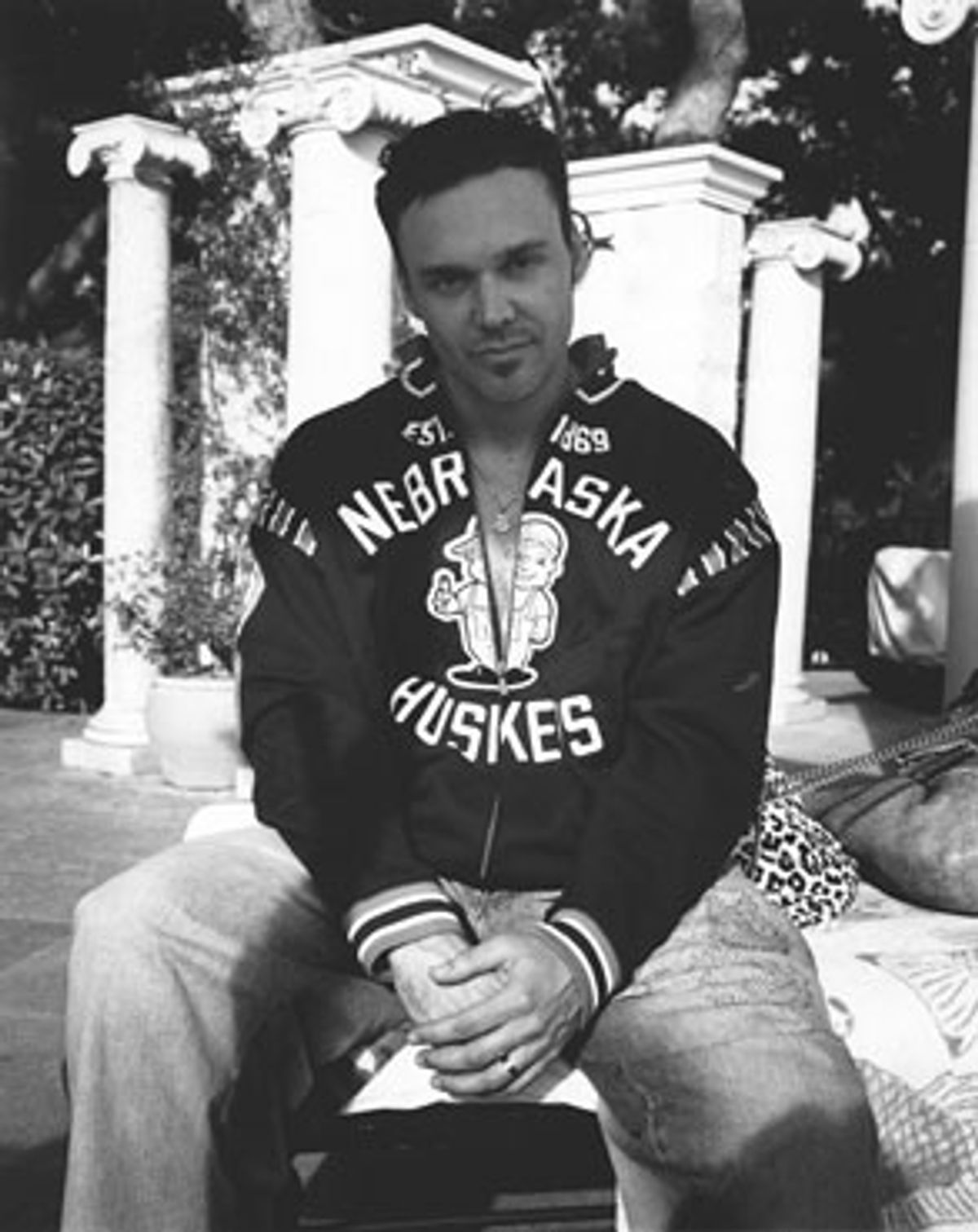

And if "Rize" exceeded my expectations, so did David LaChapelle, a soft-spoken, humble guy who was extremely talkative, even though he looked exhausted (little did I know he'd been arrested for alleged disorderly conduct after his premiere party the night before). For almost an hour, he talked enthusiastically about everything from his early days at Interview to disrespectful pop stars to the fact that the rich and the poor might have more in common than we think.

I saw "Rize" on opening night. What a reception!

Did you like it? Be honest.

I really enjoyed it. I want my mom to take this kid that she tutors in Durham, North Carolina, to see it...

Oh my god, you're kidding! Johnny, my boyfriend, is from Boone! We went to the School of the Arts in Winston-Salem -- I lived in Raleigh for a while. It's one of the best schools in the world. So your mom tutors a kid?

He had a tough childhood and I think seeing other kids who've been through the same hell and have come out of it -- it would be good for him.

We talking to several interested parties now, and we're about to close a deal [Lions Gate Films purchased the domestic rights to "Rize" for slightly less than $1 million on Monday], so she'll be able to take him to see it in a theater. We were approached by several places, but we think we've found the one that seems best for us ... I'm hoping it'll be released this summer.

I really feel this film crosses over, I don't feel that it's just a film for a certain audience. This film is for all people. You know, pop art -- "pop" means popular. Andy Warhol gave me my first job as a photographer for Interview when I was a kid. His idea was, "Oh, you can do anything." I never felt like "I'm a fashion photographer." People say, "This is so strange. You're doing a documentary." It's not strange. It's everything I love. It's dance, it's color, it's surrealism, you know, it's gospel music. It's everything I love. You follow your heart, you do what you need to do, and you can't go wrong if you're really following your heart that way. But I did not want to do an art film, and I didn't want to do a film for just the Xbox kids either. I wanted to do a film for everybody.

How did you meet Warhol?

I went to New York when I was 15, I went to School of the Arts for two years, I came back to New York when I was 17. I lived on First Avenue and First Street with this girl Vanessa, she's still in the same apartment. And my goal was to work with Andy Warhol. He was my favorite artist. So I would just go up to him and show him my pictures from high school...

So you found out where he was?

I met him in the club, the Ritz, at a Psychedelic Furs concert. And he said, "Oh, come show me your pictures." And I did, the next day. And then I just kept going back. This was way after he was shot and stuff. But he was very accessible in New York. He was such a part of New York. You would see Andy out, and the scene was smaller then. You'd see Andy a lot. I was persistent. I just really wanted to work with him.

He was so generous to me -- not monetarily, just encouragement-wise. He knew I liked Prince, so he brought me to a Prince concert. He introduced me, and I was nobody, just starting out. People would come up to him, and he'd always defer the attention onto whoever he was with, that's why he liked to be with celebrities. That's why he was like, "Oh, this is Grace Jones!" because the attention on him freaked him out. So we were at the Prince concert, and he says, "Oh, this is David LaChapelle, the famous photographer!" I was a nobody, I was a kid.

That was my finishing school, that was my college. I got to understand deadlines, understand working in the business and being around that stuff. I was like an intern, hanging out all the time and eating the leftovers from the lunches.

What was your first assignment at Interview?

It was the Beastie Boys, 1984, first picture of them ever published, in Times Square. And I worked for him every year until he died, and then I shot, just by coincidence, the last sitting of Andy. The only time I ever did a portrait of him was two weeks before he died [in 1987], so they became the last photos of Andy.

Do you find yourself wanting to do the same thing that Warhol did, to put attention on others?

I don't compare myself to Andy at all. There was only one Andy Warhol; there will never be another person like him. I can only aspire to be as good as I can, by doing what I want to do and never holding back. That was one thing I learned from Andy: He was always trying different things. He'd do photography and film and he'd pee on the canvas. He did what he wanted to do, what was really interesting to him.

Do you think as you get bigger, it's harder to stay true to that?

No, I don't think that way at all. I feel like I'm just starting out. I'm just starting a whole new chapter in my life.

Did you ever find yourself at, say, a gallery opening thinking that it was too far away from where you want to be and what you believe in?

I've shown at galleries, but pictures I showed in galleries were pictures I shot for magazines.

So it's commercial art.

Yeah, but it's everything I love. They can call it commercial, they can call it art, it doesn't matter what they call it. It's my pictures. People say, "Well, do you have your private work?" I'm like, "No, everything I do is personal." It's all personal. But I'm going to be showing this film in a gallery in the summer once we have our release. I'm not going to exclude anything. I don't believe in those ideas of high and low [art].

The image that sticks out in my mind the most clearly from your work is the one of that cool-looking Asian woman with the freckled doll face.

Oh yes. Devon Aoki. Her father owns Benihana.

Really? The picture I remember is of her holding a fish...

She's in an art gallery, in front of pictures of ice.

There was something so unforgettable about it. Was that something you composed yourself?

Yeah, they're always my concepts and ideas. That's the fun part of it.

Was that a commissioned thing?

Yeah, it's a fashion shoot, but I can pick the clothes and the setting and everything in there. For me, if there's not a shoe in it it's less interesting. I like that there's something in there that's part of the world.

So what informs your vision?

Well, "informs" is a big word. I get influenced by everything. I think we feel different from week to week. And I would never want to be doing the same thing all the time. I mean, I think you have an experience and then you're inspired to do something different. Some days you feel like being colorful and making something funny, and other days you feel like doing something very serious. That's part of being human. I don't think anyone should let their style dictate their whole volume of work, their whole life's work.

How did that perspective come into play in the making of "Rize"?

When I saw these kids dancing, I said, hey, this has got to be documented. I never thought I was going to be a documentary filmmaker, but I loved documentary films growing up. So here I was doing a documentary because I fell in love with this dance, and then that led into their lives. I thought, this is something that people need to see, something we need to celebrate.

How did you find out about these kids?

I have some friends from South Central, and they said, "Dave, you gotta see this new dance that these kids are doing, you're gonna love it." This was in 2002. So I went down there one night, into the 'hood, and I saw it, and I met Tommy (the Clown) and that was it. I went and bought a camera and we started going back and we started filming, and every free day I had off from work, I would just go into the 'hood with my little crew together, just me and some friends. And then it grew. Then we came here last year with the short ["Krumped" played at Sundance in 2004]. We realized we had a film when Elvis Mitchell reviewed it in the [New York] Times. That's when it all changed. It validated us, and Sundance validated us, and it gave us a little shot in the arm. Then we came back this year with a feature.

The thing that makes a film inspiring, I think, is its power to make you reevaluate your values, and how you spend your time, and what's important in your life. I had that feeling of reshuffling my deck after seeing "Rize." Did your perspective on what you want to spend your time doing change as a result of working on this film?

[Laughs.] Yeah. It really did.

Once you do that, it's hard to go back in the other direction. But you can do it. We'd be filming and then we'd be editing, and we'd get so into the film, we'd just get saturated with it -- in the editing room every single day. Then I'd have to go do a music video! And suddenly you're in this shocking world with people telling you they need this, and the publicist needs that. There was this one music video with such a spoiled pop star, just someone who had changed so much since when I first met them. Just being treated so ... [Pauses.] It was just bizarre, coming from a place where you have autonomy and you're working on this film, to be suddenly working with somebody who really is not that great of an artist, to put it bluntly, but who thinks that they're this great artist. And you have to humor them, "Yeah, you know, you're great."

But I found things to love in it -- you always have to do that. So I brought in these kids, I brought them into the video.

But do you ever think now, on a shoot, Well, maybe I don't need to do this kind of work anymore?

No, no, no. No, I really love taking photos and I'll never stop taking photos. Photography as a genre, I can never dismiss that. It's just that sometimes there are assignments I'm not that interested in, after working with these people here, these young artists [the dancers in "Rize"] who have so much depth and so much life, and they're so inspiring.

But there are still people who I work with -- Christina Aguilera for instance, who has this incredible voice, she treats me with such respect. I work with her, and we do these videos, and she lets me conceptualize whatever I want to do, whatever I'm interested in. She collaborates with me, and there are a lot of artists like that, ones who have an incredible gift. And you know what? We live in a very different world. Hollywood is very different from South Central. And when you are a celebrity, it changes you. I'm very forgiving of that, and I want to be with people from all walks of life. I never want my life to be about one thing. It really makes life so much more interesting, to cross into different worlds all the time.

Are you worried about exposing these kids to that world at all?

I'm not, because they want to be performers. And I think the worst thing for a performer is to not have an audience. A real performer, an artist, wants to share their gift. They don't want to sing in the shower. Van Gogh wanted his paintings to be hung in galleries. It's not that they want just recognition or attention or fame. They want to share some life. Inside there's knowledge, and they want others to partake of that same thing they feel. It's like when you see something beautiful -- say you're driving and you see an amazing sunset, and you look to turn, and there's no one sitting beside you. Your first reaction, you want to tell somebody, "Look at that!" It's almost like you can't appreciate it as much when you're alone.

That's what it is with these dancers. When I started filming them, I shined a spotlight on them, and it changed how they felt about themselves. It validated what they did, the same way Sundance validated my short. It gave me the impetus to keep going. It gave me the encouragement.

This is also very much an African-American experience you're documenting. There were parts during the film when I thought, I cannot imagine white people coming out of their houses and dancing in the street like this. So what is it that separates us?

[Laughs.] Well, it is possible for white people. I've seen it.

Well, what's the ingredient that makes that possible?

I think ... You know, you definitely find it with gay people, too. You find it in gay neighborhoods. They'll party in the streets. In the face of all that adversity when AIDS was happening, people would ask, "How could they keep going to clubs and partying?" Because they weren't celebrating it -- that was their release. They weren't being flippant to the epidemic or trying to forget it, but for those moments, they were just expressing themselves in movement. They kept dancing throughout the epidemic, and it's still going on.

Maybe marginalized people sometimes have that feeling, more, of family, than, say, people who have it all. When you got nothing to lose, when you're not trying to keep up with the Joneses and you don't really care what people think, there is more freedom. There is more sense of family and community, weirdly enough, in the ghetto, even though they always talk about the broken homes down there. As I recall, there are a lot of broken homes in Hollywood, too. And it's just exactly the same thing, but they always focus on, "Oh, the single mom in the 'hood!" But you know what? It's the same way in Beverly Hills, the absent parents so consumed by their careers. You find these giant houses and there are all these empty rooms. I go to the 'hood, I see this one little house, and it's full of life.

When the kids were talking at the premiere, it was remarkable how they all had such a strong belief system and such a clear ideology that keeps them going. They talked a lot about pain and suffering, and I wondered, does that strength come out of the bad stuff they've been through?

Two of the kids in the film were born to parents addicted to drugs. We all read about the crack-baby epidemic in the '80s. Well, here they are. Two of them have parents who are O.G. -- original gang members, original gangsters. That means they were founding members of the Crips and the Bloods. Baby Tiger Eyez's father is one of them. There's all sorts of adversity, but there's also so much love. They create family where there was none and they create art where there wasn't any. I was given every art program when I was a kid. They've had none. They've had no African studies. They've never seen African dance. They've never seen African face paint. It's in their blood.

Did you find yourself having to hold back from art-directing certain scenes?

No, I really didn't art-direct anything ... there were so many interesting things in their homes, and where they live, and in that neighborhood, that I didn't feel like we had to art-direct anything except just making sure we were in the right spot. Making sure we captured it all, so you had the feeling of that neighborhood. I was relieved not to have to art-direct anything. It was so good just to focus on their lives. There's no narration or voice-over; they spoke for themselves. I would just start conversations, and then they would just finish the conversation. I didn't want any talking heads or any celebrity endorsements. You know, like they said [at the premiere], they're the alternative to all the bling-bling. They treat the women who krump as sisters. They don't treat them as bitches and hos like they do in rap videos -- you know, Nelly taking a credit card and sliding it down the girl's ass crack on his last video? That's not their thing.

Is krumping a legitimate movement? Do you see this spreading?

They are the Seattle of hip-hop. What Seattle was to rock music, they are to hip-hop. They are the alternative, they're the Nirvana, they're the Kurt Cobains. They're a whole new generation that's rejecting that whole commercial idea of hip-hop with the cribs and the bling-bling and being Donald Trump. Yeah, they want to make their own businesses and stuff. [Miss] Prissy wants to do krump clothing, but that's just creating. They just want to work, and make things, and create. But their goal is not just to have as much money as possible, to the point of ridiculousness. They don't have that sort of greed in them -- they're very spiritual, these kids. They're on a completely different trip.

Shares