I don't remotely fit the "Veronica Mars" demographic. I was a latecomer to the whole "Buffy" thing -- something about vampires and superpowers always made me run, screaming, in the opposite direction. I never made it through an entire Nancy Drew mystery, and I only read "Harriet the Spy" once. On top of that, I've never cared too much about girls with a knack for solving crimes, and teen dramas don't interest me unless hot teenagers are attending fabulous parties, muttering witty rejoinders and pushing each other into swimming pools constantly, a cross between Dorothy Parker and "Dynasty."

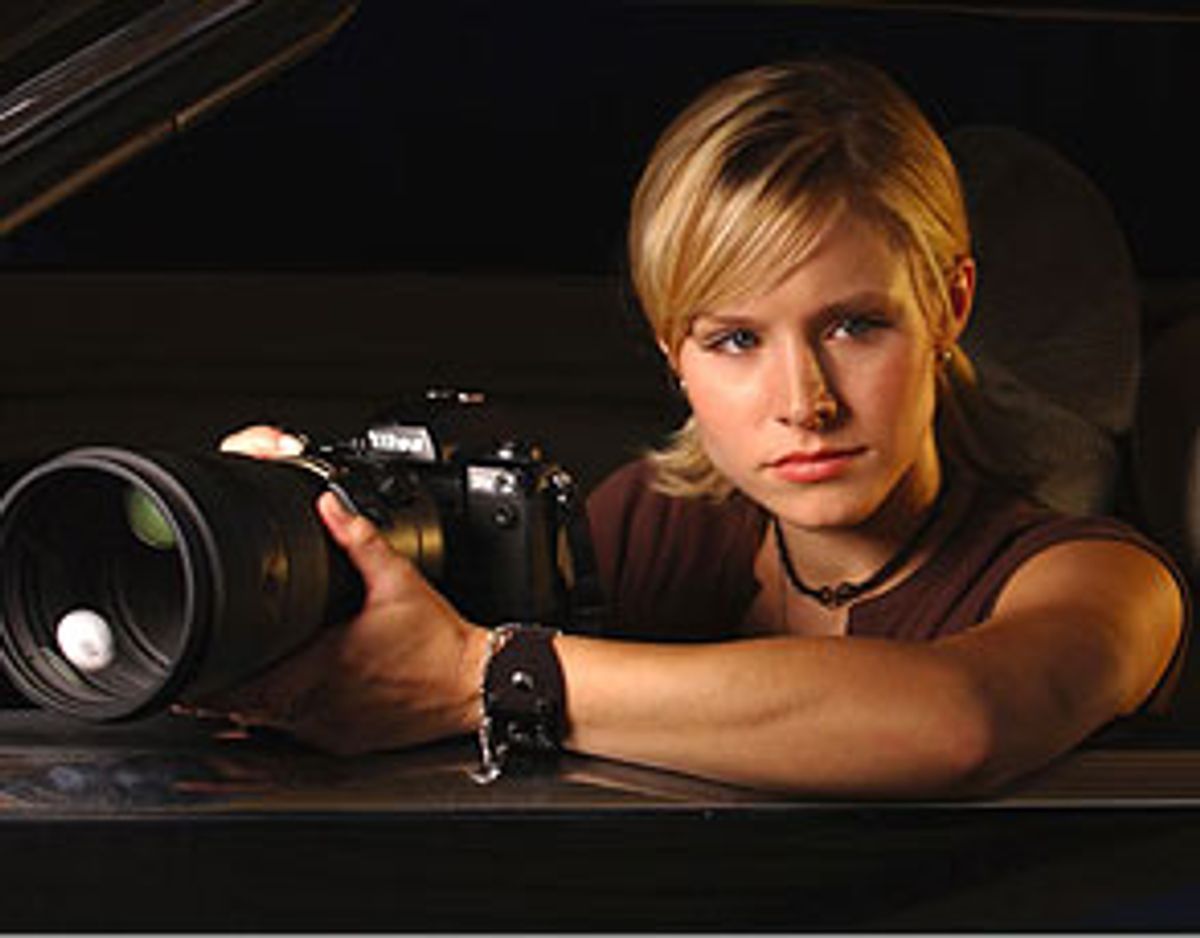

But I love Veronica Mars. I love the way her crappy attitude doesn't match her sweet doll face and her bouncy blond hair. I love her outfits, with those tall boots and short skirts and argyle socks and little cardigans, unnerving ensembles that mix one part tough tomboy with two parts trashy Catholic schoolgirl. I love that she's capable and decisive and smart and doesn't waste her time whining about her insecurities and crushes like the rest of us did as teenagers. I love the way she always thinks of the perfect, snappy retort, the likes of which would only occur to us in the middle of a sleepless night. I love that she recognizes the power of chirping like a ditzy bimbo to get access to the information she needs. I love how she makes friends with the outcasts and losers at school and refuses to socialize with the popular kids, even as she's forced to empathize with them. I love that she's been through hell -- her friend's death, her mother's disappearance, her mysterious rape -- and she's pissed off about it, but she doesn't have time to wallow. She's too busy doing professional detective work -- dangerous, high-pressure jobs! -- in order to help her daddy pay the rent. Veronica is busy and efficient but never flustered, snide but never unjust, full of feminine wiles but never slutty and pathetic. She's a role model not just for high school girls, but for grown women.

In other words, "Veronica Mars" (which returns with new episodes Tuesday at 9 p.m.; UPN) is idealized. But that's fine, because very few realistic depictions of a high school and its captives could be interesting enough to hold our attention. ("Life as We Know It" anyone?) Mumbling, zitty, painfully horny little miniature humans, putting themselves and each other down constantly, falling asleep during class, and having contests to see who can stick to their diets the longest, then breaking down and inhaling a dozen glazed doughnuts at lunchtime? Might be nice as a farce, but a one-hour drama? Besides, "Freaks & Geeks" already perfected the realistic high school drama, and it still got canceled.

High school can be overidealized, of course, as well; "The O.C.," with its steady flow of fabulous parties, witty rejoinders, and swimming pool mishaps, really has nowhere new to go, and we're only halfway through the second season. The cute kids fall in love, then break up, then fall in love again in a weightless, endlessly repeating loop.

Any really good snapshot of the high school experience, from "My So-Called Life" to a bevy of John Hughes films, reflects an uneasy mix of self-obsession, insecurity and myopic scorn. Whether it's Claire Danes or Matthew Broderick or Sarah Michelle Gellar rolling their eyes as the deluded herd ambles by, we savor their angst and bitterness as a salve for our own haunted, humbling memories of those times.

Like any high school heroine worth her weight in greasy cafeteria tater tots, Veronica Mars' mix of alienation, sarcasm and angst is palpable from across a packed gymnasium. But there's something else that sets her apart, an angry, stubborn self-confidence in the face of a very dark past, one that includes a dead best friend, a mom who skipped town, and a night when she was slipped a roofie and raped. Even with Buffy setting the precedent, this is not the sort of darkness you'd expect to find on a teen show. But as screwed up as her life has become, each week Veronica learns that the other kids at school could be facing bigger demons than she is.

This is the tasty little truth at the heart of "Veronica Mars" and one of the main reasons -- among many -- that the show has gathered a loyal audience and some promise of a second season despite unimpressive ratings. Each week, using the skills she's picked up from her detective dad, Veronica unearths the vulnerabilities and torturous circumstances behind those seemingly flat characters -- the nerd, the jock, the outsider -- who haunted us way back when. And so, along with a barrage of crimes, mysteries and missing persons, Veronica discovers that the popular jackass at school, Logan, has a self-absorbed, brutal movie-star father (played hilariously by Harry Hamlin) and a mother who, out of the blue, drives to a local bridge, parks her car, and jumps off. Duncan Kane, the dreamy ex-boyfriend who's kept Veronica at arm's length, has epilepsy, a murdered sister, and wildly dysfunctional parents to boot. And Carrie, the gossipy girl Veronica doesn't trust, who claims Veronica's favorite teacher got her pregnant? She is lying, but with good reason -- she's helping vindicate her friend, who really did have an affair with the teacher.

While such fully realized characters might be common on, say, "Deadwood," such depth is unheard of in most teen dramas. Providing this peek behind the curtain not only offers a remedy for those teenage snap judgments, it lends the world of "Veronica Mars" depth and color. We can trust, as viewers, that we'll be treated to a look at the sad or confusing or deliciously sick layers that exist underneath the pretty myth of other people's families, those layers most of us don't discover until at least our 10-year high school reunions.

But thanks to creator Rob Thomas' interest in creating a "teen noir," "Veronica Mars" transcends the slippery story slope of teen soaps with new, dramatically interesting cases to solve each episode. The soapy stuff is simply squished between story lines.

And with so much detective work on Veronica's plate, there's no need to introduce the supernatural. As great as we can all agree that Buffy was, falling back on the Girl With Superpowers thing, the way so many other shows have ("Wonderfalls," "Joan of Arcadia," "Dead Like Me," "Tru Calling"), would undermine the show's ability to feature gritty, courageously dark stories about what happens to real teenagers. By keeping his show in the realm of real situations and real tragedies that can't be solved by, say, a wooden spike, some nifty instructions from God or a talking tchotchke, the pressure on Veronica is far greater -- and her determination and strength in the face of daunting obstacles and emotional pressures are that much more impressive.

Of course, there's also that larger, season-long narrative arc involving the murder of Veronica's best friend, Lilly Kane, and the mysterious disappearance of Veronica's mother. Unlike the empty whodunit of "Desperate Housewives," with its weak little clues that lead nowhere, the Lilly Kane murder is a worthy mystery for Veronica: It involves her murdered friend, her dad, her mom, her ex-boyfriend, and the possibility that Jake Kane, Lilly's dad, is her biological father. In Tuesday night's episode, Veronica actually comes face to face with her mother and confronts her about skipping town after the murder. And the last two episodes of the season sound like real cliffhangers: In the second to last, we find out what happened the night Veronica was raped, and in the last episode, we find out who murdered Lilly Kane.

All of which probably sounds mighty heavy to those who've never seen the show, but after an uneven start (the local tough guy, Weevil, seems to have lost his anachronistic motorcycle gang posse, finally ridding us of bad "Happy Days" flashbacks), "Veronica Mars" has evolved into an organic, seamless blend of dark and light moments, drama and comedy, noir and upbeat sleuthing. The humor, in particular, gives a somewhat dark show a bouncy pace, but still feels natural to each scene and never stands in the way of the plot or the pace. When, for example, Veronica tells her friend, after getting dressed in black rubber Madonna bracelets and a black bustier for the '80s dance at school, that she feels like Manila Barbie, it's just a passing comment that's not played too hard for laughs like, say, some of Seth Cohen's lines on "The O.C."

Of course, there's always been something sort of kitschy and stagey about Adam Brody's Seth -- he's consistently funny, but the steady flow of quips always takes precedence; instead of inhabiting his world, he floats around in it weightlessly like Puck of "A Midsummer Night's Dream," commenting on the action but never fully participating in it. In contrast, Kristen Bell plays Veronica as a confident, skillful wiseass without throwing us any winks. You could never predict, glancing at her cutesy face on a promo for the show, that you'd buy her as a sleuthing prodigy. But with the complicated mix of emotions that flicker across her face -- without the typical, eye-darting, pursed-lip action of your Neve Campbells or Mischa Bartons -- it's easy to accept her as a real teenager.

The rest of the cast is remarkably odd and likable. Percy Daggs III is fantastic as Wallace, Veronica's easygoing sidekick, and Jason Dohring is so good as the high school jackass, it's pretty much impossible to imagine that he's not a serious jackass in real life. Meanwhile, Enrico Colantoni, most recognizable from his role as Elliott on "Just Shoot Me" (or, as an unforgettable alien in the movie "Galaxy Quest"), may be the most original, offbeat dad ever to appear in a teen drama.

In fact, given the talent of the cast, the witty but still substantive dialogue, the tight, satisfying story lines, and a slowly unfolding mystery that pulls viewers back each week, it's amazing that "Veronica Mars" isn't much, much more popular than it is. But then, TV audiences are a lot like high school kids: self-absorbed, shortsighted and hopelessly flaky.

Shares