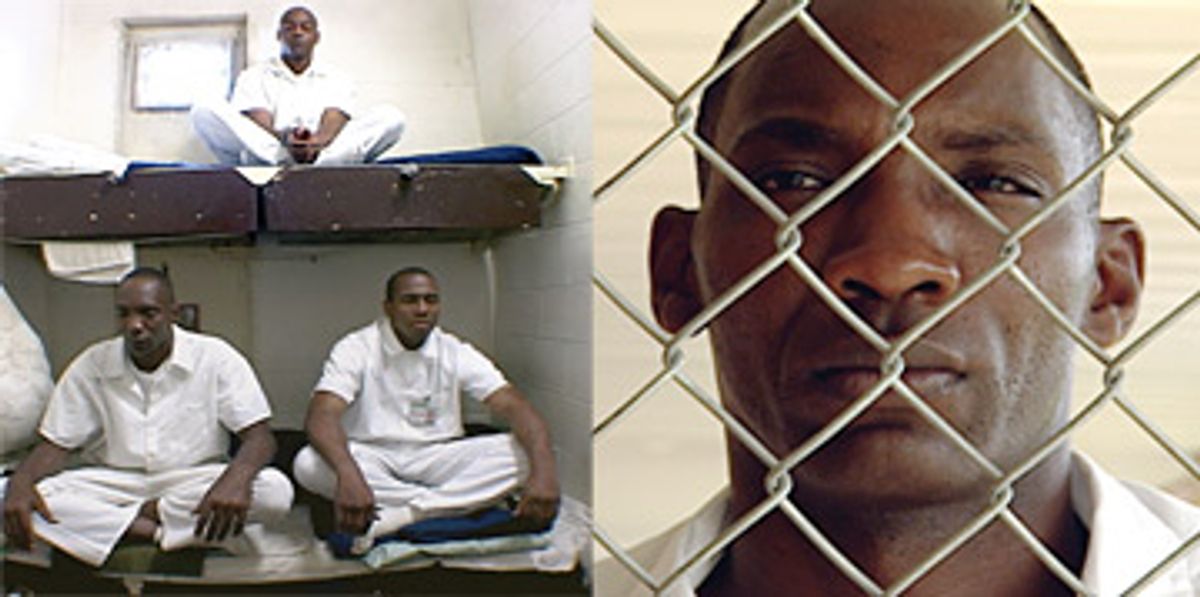

Photo courtesy of Balcony Releasing, Ltd.

Prisoners at Donaldson Correctional Facility in Bessemer, Ala.

Donaldson Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in Bessemer, Ala., that houses the worst offenders in America's direst state prison system, does not seem a likely venue for a Buddhist meditation retreat. It's a dank-looking brick structure right out of "The Shawshank Redemption," wrapped in barbed wire and electrical fencing and set in the pine woods along the red-clay banks of the Black Warrior River. Many of its inmates will never see the outside world again. Maybe the point of Jenny Phillips, Andy Kukura and Anne Marie Stein's documentary "The Dhamma Brothers" is to argue that there could be no place where 10 days of solitary and silent introspection are so valuable and so necessary. ("Dhamma," as many readers will recognize, is the Pali word equivalent to the more familiar Sanskrit term "dharma," meaning both the body of Buddhist teachings and the operations of natural law.)

As someone with a strong constitutional allergy to New Age-flavored self-actualization rhetoric (a residue of my 1970s childhood in Berkeley, Calif.), I approached "The Dhamma Brothers" with considerable skepticism. Any real Buddhist would say that's as it should be. But listen: Whether this movie is channeling Siddhartha Gautama himself or just a potent form of the placebo effect, it takes you on a thrilling and hopeful voyage through a very dark place. Furthermore, it does not require the suspension of disbelief in anything specific, beyond, I guess, the possibility of seeing oneself clearly. Mind you, that's no small thing to believe in.

Certain grains of salt apply: "The Dhamma Brothers" is more a work of advocacy than of journalism, and makes no effort to hide that fact. Co-director Phillips is a therapist and anthropologist who has worked in prisons for years, and played an instrumental role in convincing the warden at Donaldson to experiment with Vipassana or "insight meditation," an ancient Indian-Buddhist meditation technique that has lately been imported to the West in various semi-secular forms. The Vipassana course at Donaldson was taught by followers of S.N. Goenka, a retired Burmese businessman turned global meditation apostle. (I suspect that Phillips is a practitioner of Goenka's method as well, although beyond a link in the closing credits she avoids any overt infomercial touches. I further suspect that Goenka is a controversial figure in Buddhist-meditation circles, given his assertion that he is the only true heir to a 2,500-year-old tradition. Maybe some of you can fill me in.)

If you set those issues aside and watch the movie, it's clear that many of the three dozen Donaldson prisoners who took the Vipassana course found it a wrenching and transformative experience. By definition "The Dhamma Brothers" is anecdotal and not scientific (there is evidence about the psychological and even physical benefits of meditation, but you won't find it here), and the film is honest about the fact that some prisoners simply saw the course as a chance to get off the cell block. But several say the long hours of silent meditation focused on their own bodily and mental states -- for the first nine days of a Vipassana retreat, participants observe 24/7 "noble silence" -- brought them face to face for the first time with what they had done and why they were there. They confronted anguished memories of dead parents and dead children, and even began to think about the families of those they had killed. (All four of the men that Phillips and her co-directors profile in detail are convicted murderers.)

"The Dhamma Brothers" builds internal tension effectively, especially when you consider that its core "action" consists of a group of men sitting on cushions in total silence. (Of course, silence in a place like Donaldson is a rare and strange thing.) Phillips et al. move back and forth from the oppressive environment of Donaldson to the four men's stories -- each of them pretty horrifying -- about what they did that landed them there. We see the two beatific Vipassana teachers arrive, who insist on living inside the prison alongside a bunch of hard-case criminals during the 10-day retreat. We see the warden and the correctional officers move from open skepticism to a baffled acceptance, and we get a little comic relief from the citizens of nearby towns. (One lady in a ludicrous wig reports that she doesn't believe in Buddhism "or any other kind of witchcraft.")

You don't have to buy much of the Vipassana ideology to understand why the men who made it through the retreat felt a tremendous sense of brotherhood and accomplishment. (Most have maintained their meditation practice, and most returned for a second retreat a few years later.) These men have been incarcerated and abandoned, perhaps for understandable reasons, and locked up to die in a place of total hopelessness and nihilism. Suddenly people arrive who propose to treat them like adult human beings capable of a difficult emotional process of self-examination and self-discipline.

That process could just as well have been conducted by Franciscan friars or Hindu swamis; it could have involved listening to Brahms' Third or contemplating the wonder of subatomic particles. Every human culture has its own contemplative tradition, something our BlackBerried civilization neglects at its peril. (That said, the intense passion and commitment conveyed in what we see of the Vipassana retreat will make many viewers curious. If this film is meant as a recruitment tool, it's a good one.)The question asked by "The Dhamma Brothers" is not easy to answer, but in a society torn between Dr. Phil's couch and the prison-house it's worth asking: When we lock people up who have done terrible things, do we owe them the same chance to reshape themselves the rest of us take for granted?

"The Dhamma Brothers" opens April 11 at Cinema Village in New York, with further engagements to follow.

Shares