It's taken more than a full decade for the most widely demonized and vilified music scene in rock history -- the Norwegian black metal scene of the early to mid-'90s -- to get anything close to a fair treatment in a documentary film. In truth, the job isn't finished yet. As crafty and compelling as Aaron Aites and Audrey Ewell's "Until the Light Takes Us" is, it may go too far in its understandable desire to correct the bias and prejudice of mainstream journalism.

Black metal burst onto the international scene like an explosion of media catnip 16 or 17 years ago with a wave of church burnings in Norway and other Scandinavian countries that destroyed numerous historical landmarks, including the legendary Fantoft stave church, originally built in 1150. A few weeks after the fires started an articulate young musician named Varg Vikernes (aka Count Grishnackh, of the one-man band Burzum) discussed them with a reporter, suggesting that he knew who was responsible and elaborating a complicated litany of motives, from neo-paganism and anti-Christianity to Nordic nationalism and anti-Americanism.

Vikernes was immediately arrested and almost as quickly released; indeed, while he was later convicted of many other crimes, it remains unclear whether he started the Fantoft fire. Nonetheless, all his erudite self-taught ideology, much of it crazy but a lot of it surprisingly insightful, got almost instantly boiled down to one concept: Vikernes was a Satanist, and he and his fellow devil-worshipers were running amok in northern Europe.

This turned Oslo's tiny black metal scene -- three or four bands, a storefront and a basement record company -- into Pop Culture Public Enemy No. 1 and, of course, made millions of teenagers around the world yearn to sign up, without the slightest idea what they were signing up for. Copycat church attacks followed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, often accompanied with spray-painted pentacles and 666's and so forth, and whatever had once been distinctive about the Norwegian scene just became, in Vikernes' words, "a bunch of brain-dead heavy-metal guys."

But as Aites and Ewell's film reveals -- the two American filmmakers moved to Norway for several years to gain the trust of their subjects -- both the music and the ideology of black metal were always more interesting than that summary suggests. With its emphasis on coldness, darkness and hardness and its Nordic, often symphonic sense of space, the music of Vikernes' Burzum and such bands as Mayhem, Gorgoroth, Darkthrone and Satyricon is surprisingly varied and weird, and often doesn't sound much like rock at all.

Interweaving grainy home videos of early Oslo live shows and interviews with survivors of the scene (at least two of whom appear anonymously), Aites and Ewell depict a vibrant, adventurous and often ghoulishly self-destructive world, where conversations about the negative effects of Christianity, American-style democracy, NATO and commercial globalization sometimes blended into outright nihilism. Even before the church burnings began, Mayhem vocalist Pelle Ohlin (aka "Dead") lived up to his nickname by literally blowing his brains out with a shotgun. Before calling the police, one bandmate snapped a notorious photo of Ohlin's mutilated corpse, which later appeared on the cover of the Mayhem live album "Dawn of the Black Hearts." (Seriously, don't click that link unless you're sure you want to see it.)

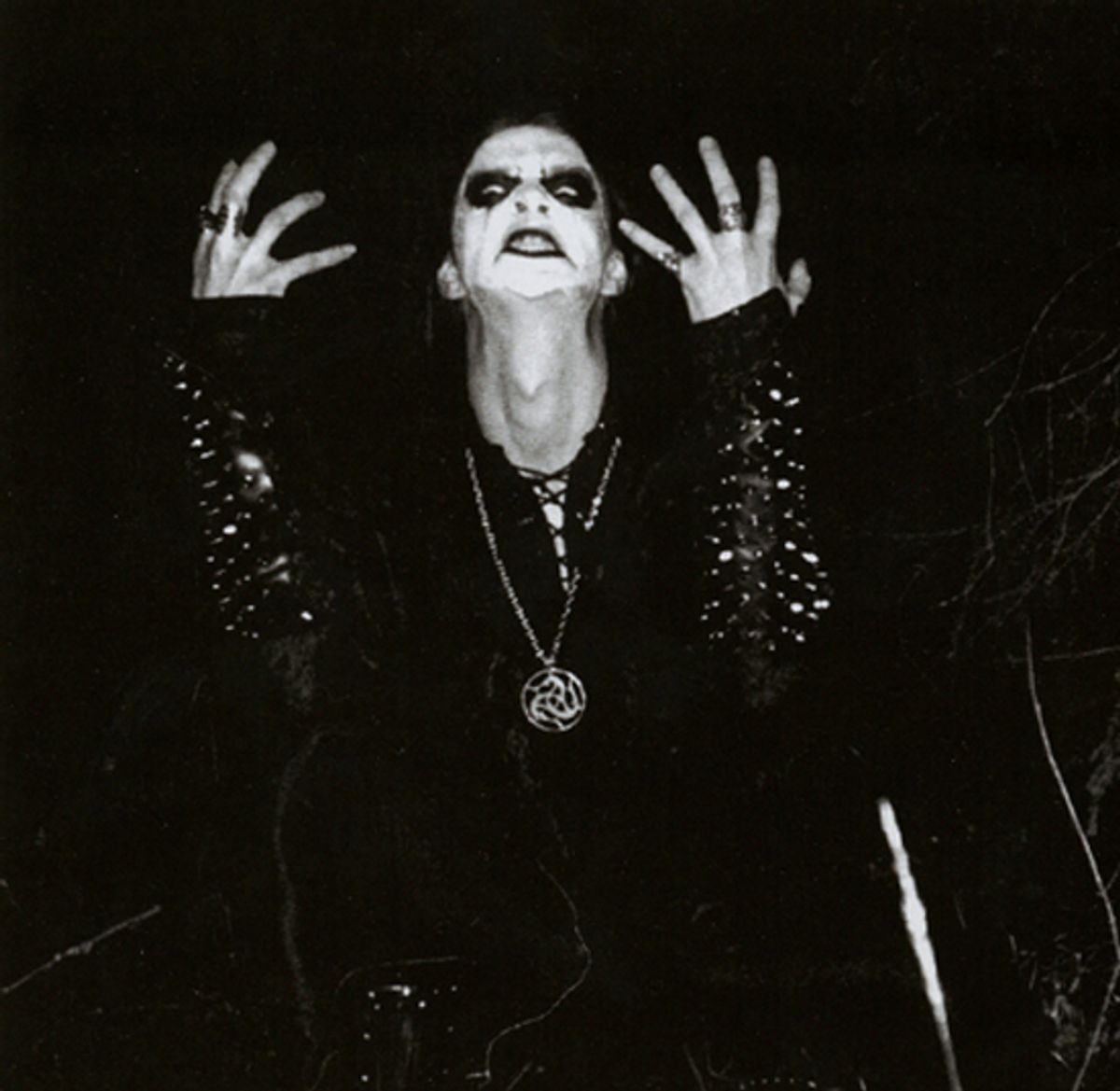

If you believe the testimony of Vikernes, Darkthrone drummer Gylve Nagell (aka Fenriz) and Satyricon drummer Kjetil Haraldstad (aka Frost), no one in black metal ever wanted to get famous or reach a mass audience, let alone spark an international trend of kids in corpse paint and black overcoats. Against the changed landscape of multicultural 21st-century Europe, musicians like Fenriz and Frost -- who were never directly involved with Vikernes' quasi-terrorist campaign -- seem semi-reconciled to their fate as professional entertainers, scraping out a living deep into middle age from the stylized remnants of adolescent pain and anger.

Neither of those guys, likable and wounded characters that they are, has the star power or philosophical depth of Vikernes, whom the filmmakers interviewed extensively in the relatively posh surroundings of his Norwegian prison cell. (Vikernes was released last May, after "Until the Light Takes Us" was completed.) With a tidy little goatee and a short jailhouse haircut, he looks like an unusually gym-toned specimen of late-30s academic. Loquacious and funny, he discourses at length, and in excellent idiomatic English, on the many crimes of Christianity and American-style commercial capitalism, which he blames for uprooting indigenous religious cultures not just in the Nordic countries but all over the world. He makes the church fires sound almost innocuous, a slightly overzealous effort to make the public "wake up" to the evils of mainstream religion.

That's all fascinating as far as it goes, but to some degree Vikernes is playing his liberal American guests, coming off as a Robin Hood combination of anti-globalization activist, Situationist intellectual and neo-Norse acolyte of Odin and Thor. In fairness, Aites and Ewell pull back the curtain on Vikernes little by little, revealing first why he spent so long in prison (for a gruesome crime whose details he recounts without emotion) and then the precise nature of his objections to Christianity. Its repression of women and gay people? Um, not exactly. Its crushing of open dissent and heresy? Its toadying to despots of all stripes? No and no. But the fact that Christianity is a historical offshoot of Judaism -- now that's a problem.

Do Aites and Ewell owe the viewership a clearer explication of Vikernes' ties to white nationalist groups, his long record of troubling racial, sexual and religious rhetoric and his public flirtation with Nazi ideology? You won't learn this in the film, for instance, but Vikernes is viewed as the philosophical father of the musical-political subgenre called "National Socialist black metal," or NSBM. Or is it fairer to this disturbing and complicated figure to present him on his own terms, without recourse to prejudicial buzzwords? (For the record, Vikernes has not called himself a Nazi since the late '90s, preferring the invented term "Odalism," said to signify "paganism, traditional nationalism, racialism and environmentalism," along with an opposition to modern civilization in all its forms.)

I can see both sides of the argument, and I've long been interested in the "Ezra Pound problem," meaning the tendency of underground aesthetic rebels to become enmeshed in noxious political ideologies. Maybe it doesn't invalidate Vikernes' music in particular (his forthcoming post-prison album was originally to be called "The White God") or the entire anti-modernist, atavistic spirit of black metal to observe that it comes with some heavy and evil-smelling baggage. But I suspect it's worth, you know, actually noticing and talking about.

"Until the Light Takes Us" is now playing in New York, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Mich., and Providence, R.I. It opens Dec. 8 in New Orleans, Dec. 10 in Houston, Dec. 11 in Los Angeles, Jan. 8 in Chicago, Jan. 15 in Seattle, Jan. 22 in Milwaukee and Jan. 29 in Denver, with more cities to follow.

Shares