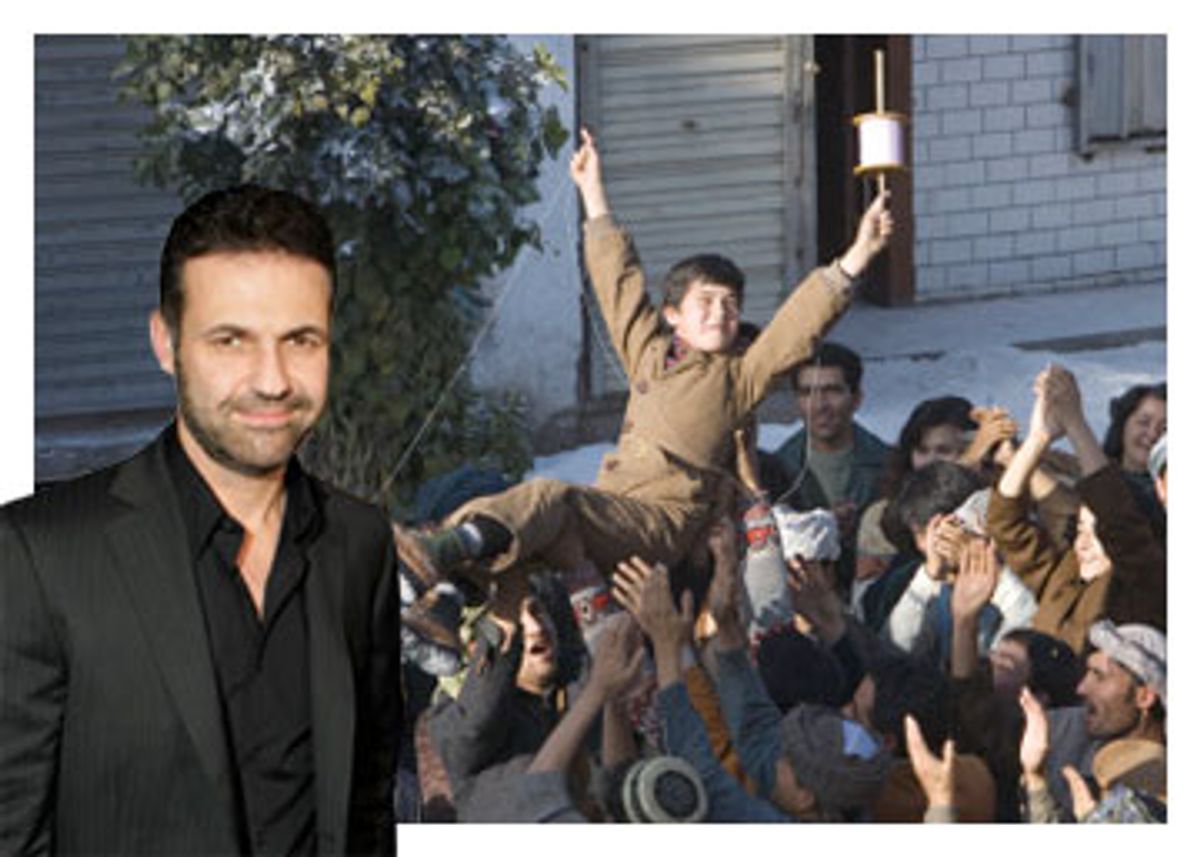

In March 2001, Khaled Hosseini started writing "The Kite Runner," his semiautobiographical saga about coming of age in Afghanistan and coming to America after the Soviet invasion -- and returning to Afghanistan after the rise of the Taliban.

Six months into his work on the book, the events of 9/11 occurred. The times were cataclysmic, but for Hosseini, a practicing physician with an unpublished manuscript, the timing was propitious.

It was the year many Americans first learned where Kabul, the country's capital, was and who the Taliban were. To a great extent, Americans had pictured Afghanistan as a land of cave-dwelling terrorists. "The Kite Runner," which became an international bestseller -- translated into 40 languages, it has sold 8 million copies worldwide -- helped fill in that very rudimentary picture. The book has served to bridge the cultural divide and surmount headlines with its story of a young boy contending with political and personal turmoil.

The first novel published in English by an author from Afghanistan, "The Kite Runner" is the story of Amir, the young son of a well-to-do Afghan diplomat in 1970s Kabul. Amir's close but ambivalent friendship with -- and lifelong shame regarding -- his Hazara servant Hassan is at the heart of the book. It is a relationship that haunts Amir from Kabul to California, where Amir and his father move after the Soviets invade Afghanistan.

Like Amir, Hosseini grew up in an affluent household in Kabul in the 1970s, though the author also spent part of his childhood in Tehran, Iran, and Paris. In 1980, he and his family were granted political asylum in the United States and moved to San Jose, where he still lives with his wife and two children. It wasn't until 2003, with his book in production, that the author returned to Afghanistan to visit the land of his birth and retrace his character's footsteps.

While Hosseini drew much of the book -- its cultural richness, accounts of ethnic conflicts, even its evocation of annual children's kite contests -- from his own experience, Amir's harrowing story is fiction. Beautifully written, startling and heart wrenching, "The Kite Runner" is also an episodic page turner. It's a winning recipe for book club consumption -- and film adaptation.

Now, as he anticipates the premiere of the movie version of "The Kite Runner," the 42-year-old author, who no longer practices medicine and whose second novel, "A Thousand Splendid Suns," was published in May, talks about Americans' positive response to his book and some Afghans' outrage at the movie, which includes a 30-second scene depicting the rape of a boy, played by a 12-year-old Afghan, Ahmad Khan Mahmidzada. (Mahmidzada's parents said they had no knowledge of this plot point when they agreed to let their son act in the movie.) Word of the rape scene has triggered threats of violence against the three Afghan child actors who appear in the film, demands that the scene be cut, articles about Hollywood exploitation -- and an ensuing P.R. disaster for Paramount, which agreed to delay the film's release until the kids were safely out of Afghanistan. Last week, the studio announced that the children and their guardians had been relocated to an unnamed city in the United Arab Emirates, clearing the way for the film's release this Friday.

Salon sat down with Hosseini in San Francisco in October, just before "The Kite Runner" premiered at the Mill Valley Film Festival.

To what extent was "The Kite Runner" a product of geopolitical timing? That is, just after Afghanistan and Afghans reached the headlines here and showed up on Americans' radar, your book comes out. Did you think, "Well, now there's finally an interest in the region" or "Now it's a marketable story"?

The timing wasn't intentional, but it kind of worked out that way. I really meant the book as a challenge to myself to write a novel. I had always written short stories and I'd written a short story called "Kite Runner" and I went about expanding the short story to a novel. When 9/11 happened, my wife really started talking to me about submitting a novel. I was reluctant at first, but eventually I came around to her way of looking at it, which was that this story could show a completely different side of Afghanistan. Usually stories about Afghanistan fall into "Taliban and war on terror" or "narcotics" -- the same old things. But here's a story about family life, about customs, about the drama within this household, a window into a different side of Afghanistan.

Do you think the book would have gotten the same attention if the U.S. hadn't been in the midst of a war in Afghanistan?

It helped the novel be published, but being published and having people still embracing the book four years later are two very different things. People read the books and tell their friends to read the book because they connect with something in the story.

Americans don't always put a human face on international news. But "The Kite Runner," which was the third bestselling book here in 2005 and was voted 2006's reading group book of the year, has helped demystify Afghanistan for a lot of people. Is that icing on the cake for you?

It's a hell of an icing if that's what it is. It's tremendous for me. Fiction has the ability of taking the reader to a place they would have never gone before, and putting them in the shoes of characters who are radically different than they are.

One of the most common comments I get -- from my Web site, e-mails or letters -- typically goes something like this: "I have to be honest with you, I really didn't know much about Afghanistan and I frankly didn't care much, and then somebody said you have to read this book and then I kind of reluctantly agreed, and all of a sudden Afghanistan has become a real place to me and the Afghans have become real people and I see the parallels between my life here and the life of the people in this completely remote country, and now when there's a news story about Afghanistan -- be it a bombing or an attack on a village -- it registers on a very personal level." That to me, that's wonderful.

Did you create the character of Amir as a stand-in for you?

No more than most first-time novelists who write in the first person. The setting in 1970s Kabul, the house where Amir lived, the films that he watches, of course the kite flying, the love of storytelling -- all of that is from my own childhood. The story line is fictional.

What about the relationship between Amir and his servant, Hassan, a friendship that nearly transcends class lines but does not in the end. Was that based on something from your own life?

There was a Hazara man who worked for my family for a couple of years and he was much older, 38. We became pretty good friends. He helped me fly kites and I helped him learn how to read; it was a lovely relationship and he eventually went away. The really striking thing was that I finished [writing] the entire novel without once consciously thinking of him. And then when I was done I said, "Oh my God, of course that's where this character comes from!" -- which was startling to me, the powers of the subconscious.

In the story, the character of Amir spends much of his young adulthood regretting his youthful actions, his bad choices and their lifelong consequences. Are the movie's themes of betrayal and cowardice drawn from your own experience too?

You don't want to draw too many parallels, but if there's a theme in the book that I have felt in real life it is having led a somewhat comfortable, privileged life amid real poverty and amid people who face a life of hardships. There's a line in the novel and film where Amir says, "I feel like a tourist in my own country," and I felt that way when I went back to Afghanistan [for the first time] after 27 years. There was a sense of coming home and at the same time I felt like an outsider and a tourist.

When Amir goes back to Afghanistan, after some 27 years, and rights his wrongs, the book -- and now the movie -- takes on a redemptive theme. Your second book, "A Thousand Splendid Suns," for which Columbia Pictures owns the movie rights with an eye toward a 2009 release, also ends with redemption. Hollywood loves redemption. Did you envision the cinematic possibilities of an uplifting ending when you wrote the books?

I never thought "The Kite Runner" would make a good film. It felt to me that so much of the action was internal, was inside of this guy's head, and that the meat of the book was the grappling inside Amir's mind about his identity, the things he's done, about who he is. It wasn't until I read [back over] the novel a couple of more times that I saw that there was a cinematic quality about it. When I'm writing, I need to see exactly how the scene is choreographed and where characters are in relation to each other. I guess that lends itself to cinematic adaptation.

How in the world will they make "A Thousand Splendid Suns" into a film? Its depictions of cruelty to and abuse of women by their family members and the government in Afghanistan are probably even more horrific than even the most disturbing images in "The Kite Runner."

In terms of controversy in the Afghan community, I think that book is more palatable. There are issues [addressed in the book] about women, but the issues about ethnic tension are the sensitive ones in Afghanistan. If that film is ever made, I don't think we'll be facing the same sort of controversy.

In the film of "The Kite Runner," even though the rape is not explicitly shown -- we only see the boy's pants coming down -- there were rumors in Afghanistan that the studio planned to use computer animation to create CGI genitals and make the scene more graphic. There have been threats against the actors. An online petition was launched to "save the 'Kite Runner' boys." Had you anticipated that the rape scene would be problematic?

I thought it would raise eyebrows, but if anybody, either me or in the production, thought it would lead to the actors actually fearing for their lives, I don't think anyone would have gone forward. Certainly, they would not have cast actors from Afghanistan. The controversy reflects that things in Afghanistan have changed to some extent, certainly in the last year or two. Things have become more violent. It's a more dangerous place than it was. It has slid back and there's a new element of criminality and violence there.

Would you have advocated cutting the scene to protect the children?

I don't see how you could maintain the integrity of the film if you removed the scene. You'd pretty much have to scrap the whole thing. The scene is pivotal. Without it the story falls apart because, in many ways, that moment, the act in the alley, is so reprehensible -- a simple punching wouldn't have the same effect. It would really strain the limits of plausibility if this guy [Amir] were now marked for life [emotionally], with all the years of carrying the guilt. The scene is necessary, but I think you have to look at the film in a more panoramic way and not let one scene stand for the whole film.

I'm confused by the Afghan response. I've read of Afghans saying, "Rape is a taboo subject in Afghanistan, as is homosexuality" and "the culture and religion look down on those things." Doesn't showing the rape of a Hazara by a Pashtun reveal an underpublicized discrimination against an Afghan minority group by the dominant, majority ethnic group? Weren't you revealing the atrocities, not condoning them?

How anybody can see this film and walk away with the conclusion that it supports rape is unfathomable to me. This is a film that denounces what happened in that alley, not one that endorses it. It brings to light some of the terrible things that have happened in that country. The scene is pivotal, but the film is not about that scene. It's not about sexual predators.

Do you worry that the movie version of your novel, with its potential to create empathy, has been eclipsed by this controversy?

I hope this controversy hasn't overshadowed the fact that this is a film about good things -- about the virtues of tolerance, friendship, brotherhood and love and harmony -- and that it speaks against violence. There's a lovely scene in the film where Amir, in a moment of distress and personal anguish, goes to a mosque and prays. How many times have we seen Muslim characters in a film pray -- in that kind of very spiritual moment, piously? Usually when they do, in the next scene they're blowing something up. And I'm proud of the fact that Muslims around the world will see this character performing this ritual exactly in the way that it was meant to be performed.

Shares