It sounds like a highbrow fairy tale: an unsuccessful artist turned cable TV host snags an interview with one of the world's most reclusive and glamorous art stars, Cindy Sherman -- and the two fall in love. This is what actually happened to Paul Hasegawa-Overacker, aka Paul H-O, who uses it as the premise for the documentary he co-directed, "Guest of Cindy Sherman." But to cling too tightly to that romantic story line is to seriously misrepresent this movie, which is screening this week at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York and is slated to run eventually on the Sundance Channel.

In fact, "Guest of Cindy Sherman," which was co-directed by Tom Donahue, feels more like three or four docs fused into one entertaining (and sometimes squirm-inducing) concoction. We get a sidelong view of the art world and its symbiotic relationship with commerce and celebrity, as well as an exploration of the awkward life of a famous person's "plus one." (H-O's own complaints are bulked up by an amusing interview with Elton John's companion, David Furnish.) At the center of it all is Sherman, in a fragmented portrait of a woman H-O calls "the most famous mystery girl of art," a photographer who has used her own image as the basis for a hugely influential body of work.

All this is strung together with H-O's confessional voice-overs, which present him as a goofy dude who has stumbled into the force field of a radiant, powerful woman and found himself devastated by his own lack of stature and lost sense of self. "I'd sort of been swallowed up," he complains. For five years he tags along as Sherman attends galas, hobnobs with celebs and collectors and jet-sets around the globe, spending his days as "the person hardly anyone wants to talk to." The final blow, at least as he represents it, may just be when H-O brings Sherman to see his therapist in an attempt to save their five-year relationship, and the therapist chooses to take her on as a client, jettisoning him. "Even my shrink would rather be with Cindy!" They eventually break up, though he carefully avoids showing any of the actual drama on-screen.

"Guest of Cindy Sherman" arrived at Tribeca wreathed in controversy: Sherman has officially disassociated herself from the doc, even going so far as to apologize to friends who are interviewed in the film for involving them. However, Sherman herself comes off surprisingly well -- whether working in her studio (where we watch her experiment with an endless permutation of outfits and makeup until she finds the perfect amalgam) or chatting with her sister. H-O says that Sherman got something close to final cut (at least as far as her own appearances are concerned). But for an artist whose work revolves around manipulating her own image, and yet who has very deliberately shielded herself from the publicity machine, it must feel like very unwelcome exposure -- by an ex-boyfriend, no less.

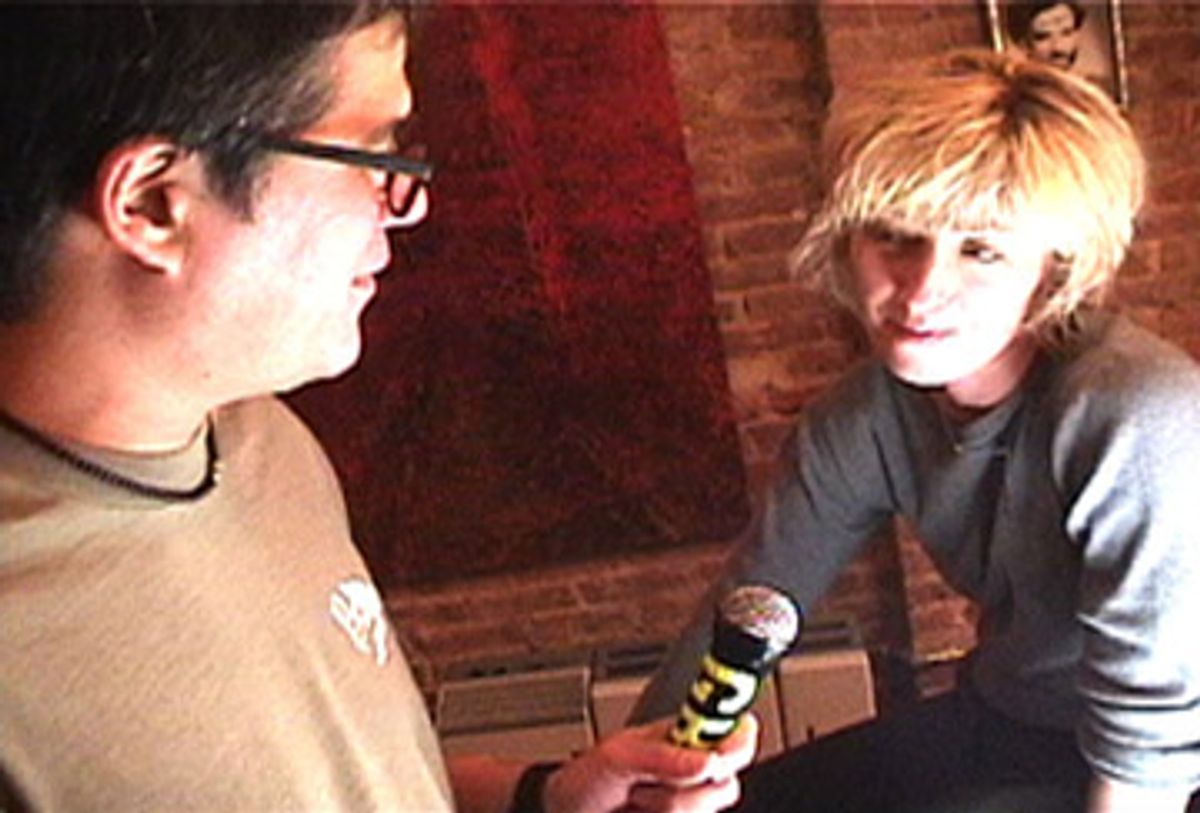

Paul H-O spoke to Salon at the Tribeca Film Festival. Watch video from the interview here:

You started your Manhattan cable access show, "Gallery Beat," in 1993. You and Walter Robinson (then Art in America editor) really were the "Beavis and Butt-head" of the art world. You had a lot of fun with the show.

I had been an artist for 25 years, and I'll tell you, I took a real beating from that experience. The art world is extremely psychologically brutal on the psyche of the artist. It's like "Survivor." You come out of art school and, immediately, half of the people just drop off the list of "I want to be an artist" because they just take a look at it and go, "Ah! Not prepared." Almost everybody else is gone within five years.

By 1993, you had been through the insane '80s art world boom and then there was this big bust -- egos weren't running as high.

No, and "Gallery Beat" was just rocking. I shed my artist mask. I could just say, I am done with "the art." Because you know, as an artist, I was just so tired of having to deal with the competition and having to kiss the asses of dealers, collectors, curators. And in a lot of ways, these people are just really boring. Artists are a lot more exciting, interesting, beautiful and sexy.

So "Gallery Beat" really put the focus on the artists, and at a certain point you met Cindy Sherman. What did she represent to you?

I'd been doing the show for quite a few years. And public access [cable TV] is a labor of love. We did have sponsors, but we only made about $10,000 a year. I was a carpenter! So, yeah, Cindy Sherman represented the top of the heap. And mysterious. She was the most famous mystery girl of art. Not only was she the heavyweight, the 800-pound gorilla, but she was also inaccessible. She and her dealers had brilliantly developed this image, which was so smart. And that basically was, "Don't talk to the press."

That was something that she had decided to do?

Well, it was easier for her to do, because she's a shy person. And actually her dealers are pretty low-key people, too, so it was a pretty brilliant plan by pretty brilliant people. You know, "Cindy, don't talk to anybody. Don't even title your work!" Do you know her work's not titled? All of the titles that have been given to the work, "Film Stills" and "Centerfolds," have been given by other people. It's all just untitled with a number.

It wouldn't be so weird, except that her work is so focused on her own image. You start to desperately want to know who Cindy Sherman is.

Well, especially someone who becomes such a celebrity figure within the art world and beyond.

You ended up doing a series of interviews with her [for "Gallery Beat"]. Did you ever discuss with her later why she let you into her studio when she wasn't talking to anybody else?

She liked "Gallery Beat," thought it was a funny show. She thought I was cute, and when I saw her, I thought she was cute, too. I think it was a little bit of love at first sight. At least it was for me.

In the film, you and Walter Robinson discuss her like she's such a babe, which felt kind of weird to me. Even though she is obviously a beautiful woman, we don't usually think of her as a babe, since so much of her work is about camouflage and armor.

Yeah, but some of those pictures are really hot! [Laughter] Come on, the garter belt -- I definitely had fantasies about her years before I'd been exposed to her. And Walter and I enjoyed being guys. We enjoyed being non-p.c.

It's pretty obvious that we weren't taking this stuff seriously, and both of us -- as artists and as media people too -- we were pretty angry. We kind of felt like the system kept us out. We felt a little burned, so there are definitely hints of that skepticism over what goes on in the art world.

The film traces your journey from artist to cable show host to living with Cindy and becoming this kind of art world sidekick. How much did it change your life?

In the movie, I say, "You know my life wasn't like that, and all of a sudden I'm staying in Beverly Hills at the W Hotel." We're in this incredible penthouse suite, and I'm like, Whoa! This is insane. My partner and co-director Tom likes to say that I lost my identity; that's a spin we put out. But it's not that I "lost" my identity. It's just that my identity went into hibernation or was subsumed by this much greater force. That's why I called it "Cindy World." In the old days there were these things called Rolodexes with little cards. Mine had like 10 cards, and hers had 1,000. And, you know, Salman Rushdie would be in hers. Her world was a lot bigger and more powerful than mine.

Your perspective is so personal, and yet there you were with Cindy, who is on a completely different and much more controlled level.

I think "control" is the key term to use. There is so much control that is exercised, not only in her world but in the art world in general. That's why we don't know things about the art world. We don't know that art dealers are paid a 50 percent commission. Nobody in the art world questions that level of a take. They just accept it. And artists are the type of people who don't organize very well. They are all pretty much a bunch of loners just sort of stuck together. The business is strong, and they're afraid of not getting their work seen, of not being able to sell their work.

This film has caused a lot of problems for me and for people in the art world who may have something to do with the film and are worried about what the effect is going to be. I've been excommunicated, basically, from that whole level of the art world.

And Cindy has dissociated herself from the film.

Absolutely. I mean, she produced an edict, a disclaimer that she had nothing to do with the film. And I find it very curious.

She knew it was filming the whole time?

She's involved in it! She was there at the inception. She was very much part of the production. I mean, we can't use her art without permission. She liked the idea. And she went on record in the Financial Times in 2006 -- she talks about the film. She does discuss her ambivalence, but she also says, You know, if there's anybody who can make the film it's going to be Paul. I trust him to make a good film, and I think it's going to be good.

What did she think the film was at that point? Did it change?

No, it didn't change. The thing about the Cindy Sherman thing is, I'm a guest of Cindy Sherman. And what I discovered about that life with her is that I just became a component in that life. I categorically became "the boyfriend." My influence as a partner didn't really extend beyond that. And I'm not satisfied in that position. I don't like to be pigeonholed, and I never sold myself as something else.

I'm being seen as sort of an identity pirate right now. But you know what? I never changed what I was doing. I was that guy, the "Gallery Beat" guy who would say things and ask questions that other people were reticent to ask. I would ask someone like Alex Katz, "What does this mean?" And you know, the guy would look at me cross-eyed, like, "I'd like to bop you one, dude." But regular people should be entitled to understand this contemporary art. That was our whole point. We can show people what's funny, what we think, what's good. I rarely was critical of the art. I was critical of the business.

You finished the initial documentary on Cindy that you did for "Gallery Beat" many years ago, and you continued to film. Her art is all about producing images and alter egos of herself. That must have been incredibly difficult for her -- to cede control over her image to somebody else -- although she comes off very well in the film, really.

I'd say so. Talk about control -- I mean, she literally had a lot of the scenes and clips removed.

So she had final cut?

In effect. I mean we could have defied that, if we'd wanted to. But the point is not defiance. The point is that this is a story, and it took place, and we are who we are. I mean, I think her anger at the film right now is an indicator of her frustration at not having control over this thing. I know there are people who work for her -- the dealers -- who are very much against [the documentary]. They always were. Somehow they've taken it upon themselves to be the guard dogs, the protectors, the spinners.

You interviewed a huge range of art world people and celebrities. Did you end up having to pull people out of the film?

No. We always presented the film accurately in the 10-minute trailer that we had produced and that everyone was aware of. And we actually used the trailer as the infrastructure of the film. We basically just took this 10-minute trailer and we made it bigger. I did a monologue, which essentially laid out the story line, and I tried it on an audience of people I had put together. People loved the story. Essentially it's the same one we have in the movie. We just didn't know what the ending would be.

Toward the end of the film, you talk to a number of other "plus ones" who talk about being partners of celebrities. And then somebody in the film asks you, "What's so terrible about it?"

Yeah, I had said, "I know what it feels like to be a wife that no one pays attention to." Afterwards, I was going, "Why did I say that?? Jesus Christ!"

For centuries women have gotten used to being the second fiddle.

I know. I know what it's like to be second fiddle, and I acknowledge my inferiority to the greater body. But then, I got tired of it. I'm sick of fabulous people. It's just a bunch of gas being blown up everyone's skirt. If Sean Penn doesn't know who you are, he's not going to blow smoke in your face, but I don't have anything to say to him, either.

So you're going to all these events and no one's talking to you, because you're not an art star or a celebrity.

I think the deal here is: Good manners never go out of style. If you have a partner, take care of your partner, you know? That's the story with Elton John and David Furnish. It was just by happenstance that I ended up sitting next to David at one of these big benefit dinners, and we were trading stories about getting shafted, you know? And I said, I'm making this movie, and he was like, I'm there.

So watch out for the place card. Be careful of who you invite. And be conscientious, because it can really bite you in the ass.

Shares