Jesus' Son

Directed by Alison Maclean

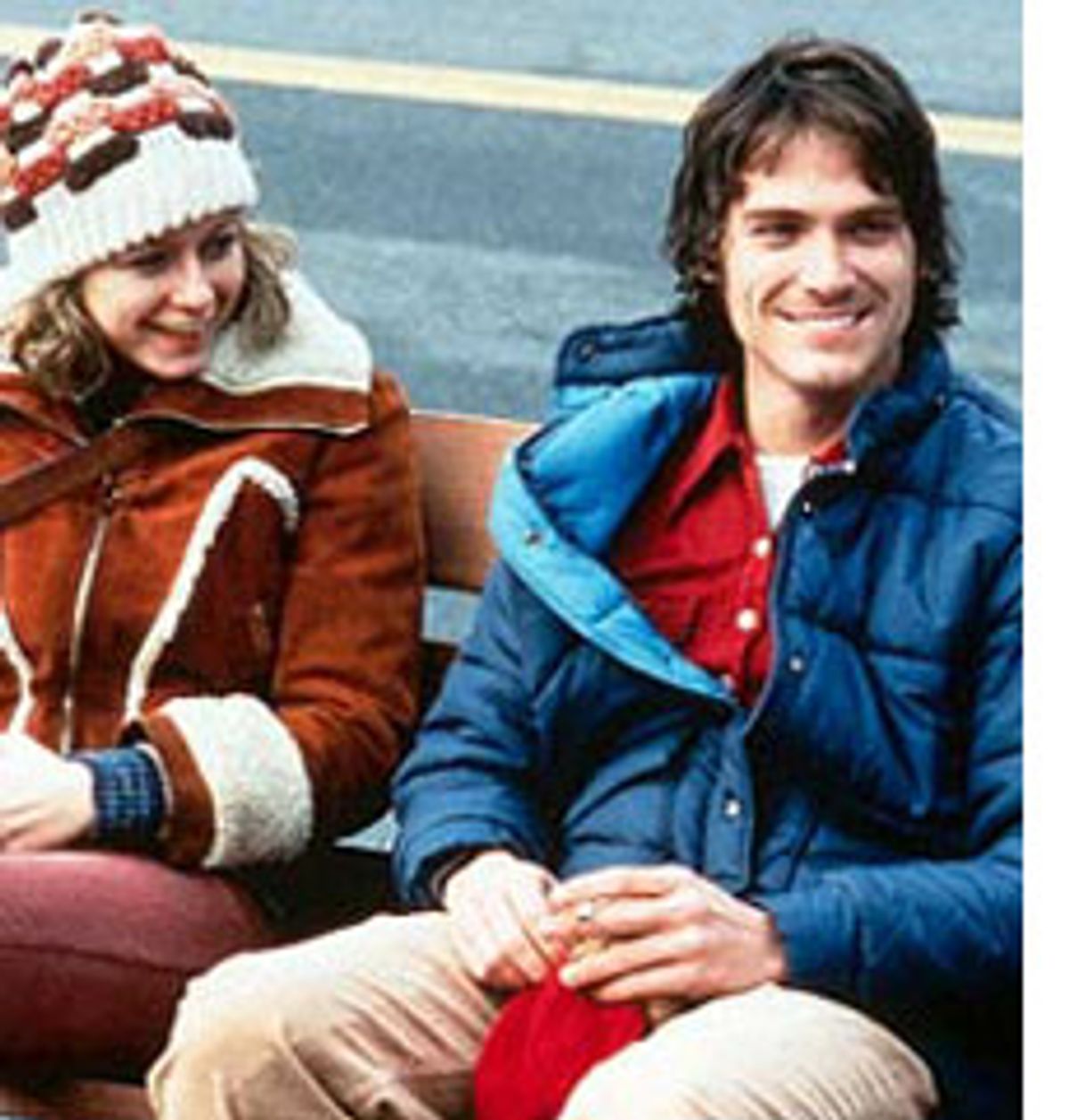

Starring Billy Crudup, Samantha Morton, Holly Hunter, Dennis Hopper, Jack Black and Denis Leary

Fans of the terse tales of American deadbeat culture gathered in Denis Johnson's 1992 collection "Jesus' Son" have probably wondered how that memorable little book, with its vast internal world of despair and lambent ecstasy, could ever be translated to the movie screen. After seeing the honorable little film produced by Alison Maclean and her dream cast of offbeat Hollywood talent, I'm still wondering.

It's not that "Jesus' Son" is a bad movie; in fact it has a nobility and modesty, along with a refreshing lack of cynical attitude, that you rarely find in independent films these days. Maclean (whose only previous feature was "Crush," a New Zealand oddity starring Marcia Gay Harden) is an exceptionally talented maker of images, shooting people and their surroundings with an unphony clarity she didn't learn in film school. She and cinematographer Adam Kimmel stick to a pale palette of rainy-day and early-morning colors that gracefully capture both Johnson's depresso-Americana settings and his governing emotional tone. Surrounded by indie-film legends, the brilliant Billy Crudup -- even if he does seem to be channeling the mid-'80s weirdness of Crispin Glover -- more than holds his own as Johnson's narrator, the ruined, almost angelic boy known only as Fuckhead.

But for all its beauty, there's a contradictory, almost intangible, sense of failure about this film: It's simultaneously too faithful to Johnson's book and not faithful enough. With its cut-up, back-and-forth structure and downscale 1970s environments, "Jesus' Son" in its weaker moments suggests a barbiturate-driven version of "Pulp Fiction," in which the guns misfire and the cars don't have brakes. Maclean and her triumvirate of screenwriters (Elizabeth Cuthrell, David Urrutia and Oren Moverman, all of whom also helped produce the film) have set themselves an essentially impossible task. They've tried to shape Johnson's disjointed episodes -- which hang together mostly through the associative imagery and repetitive phrasing of dreams or memories or schizophrenia -- into something resembling a feature film plot, while retaining as much of the author's language as possible.

Crudup, in fact, spends so much time reading Johnson's prose out loud that "Jesus' Son" approaches becoming an illustrated audiobook rather than a film adaptation. I don't have a big problem with voice-over narration, which is now so widespread I think audiences have grown accustomed to it. But it works best in small doses, and the indigestible literary slabs we get here have the paradoxical effect of slowing the film down and making it feel less like the shape-shifting, insomniac world of Johnson's stories.

To create a sense of narrative coherence, and perhaps to create a female leading role, the screenwriters have boiled down most of the numerous and often nameless women of Fuckhead's odyssey into one frizzle-haired, gamine junkie named Michelle (Samantha Morton). As usual, Morton is almost supernaturally convincing as this damaged, destructive, peculiarly sexy girl in horrible bikini underwear. If you've had actual experience of pathetic netherworlds like Fuckhead's Iowa City apartment, circa 1971, you may feel the ghosts of forgotten highs creeping over you as you watch Michelle shoot up in the breakfast nook while the TV plays cartoons and Fuckhead eats Frosted Flakes.

This amplified version of Michelle (who appears in the book only in "Dirty Wedding," a grim fable about a Chicago abortion) strikes me as a mistake. Her relationship with Fuckhead goes nowhere and ends very badly indeed, so the payoff for the moviegoer who hasn't read the book is minimal. And her presence subtly but persistently weakens the fabric of the story; Johnson's Fuckhead is so lost in a terrible fog of addiction and self-absorption he can't remember where he is or tell his wives and girlfriends apart half the time. Other people are spectral presences to him, always on the verge of leaving the world and taking him with them.

"And with each step my heart broke for the person I would never find, the person who'd love me," Fuckhead reflects in the story "Out on Bail." "And then I would remember I had a wife at home who loved me, or later that my wife had left me and I was terrified, or again later that I had a beautiful alcoholic girlfriend who would make me happy forever."

The fine cast around Crudup provides Maclean with many delicate moments as Fuckhead drifts from Iowa to Chicago to something approaching redemption in Phoenix. Denis Leary is Wayne, a booze-soaked criminal at the end of his rope, without a trace of the actor's usual smirk; Jack Black is Georgie, the drug-addled hospital orderly who takes Fuckhead on a hallucinatory all-night voyage (in the story "Emergency," probably the heart of Johnson's book); and Holly Hunter is Mira, the radiant, disabled woman who becomes the first lover of Fuckhead's sober life.

But throughout it all I kept feeling that Maclean's cautious, tactful, obsessively loyal handling of Johnson's material is misguided, that she never reaches near the book's terrifying lows or giddy, out-of-body highs. When Fuckhead tells us that his day stripping copper wire out of an empty house with Wayne was one of the best of his life we have no idea why, and Fuckhead's outrageous visions -- heavenly angels at a drive-in, a homoerotic Jesus in a laundromat -- are depressingly literal-minded. "Jesus' Son" cries out for a vivid and daring translation into film, not a conscientious transcription. A director like Quentin Tarantino or Gus Van Sant, although I have serious misgivings about both, would have understood the need not just to condense "Jesus' Son" but to remake and reimagine it.

As an interior narrative of a psychological voyage into the abyss of the self and back out again, Johnson's "Jesus' Son" belongs to a tradition that includes Dostoevski's "Crime and Punishment" and Jim Carroll's "The Basketball Diaries." The former has never been filmed with much success (we'll see about the upcoming "Crime and Punishment in Suburbia") and the latter resulted in a lamentable Leonardo DiCaprio vehicle that will only be remembered as an alleged inspiration to the Columbine High School killers. I don't feel great about adopting a condescending tone toward a director of such evident and genuine talent, especially when movie theaters are full of mendacious crap. Maclean is likely to make much better films, and "Jesus' Son," with all its flaws, is worth one or two viewings. But maybe what it tries to do simply can't be done.

Shares