Can a movie that's twice as long as ordinary movies still be small? Such is the conundrum posed by "Eureka," a seemingly directionless but hypnotic odyssey through contemporary Japan that finally reaches U.S. theaters this week after becoming a film-festival sensation over the last year or so. If you've never seen anything quite like this apocalyptic, sepia-toned road movie before -- writer-director Shinji Aoyama has suggested that it's a remake of John Ford's "The Searchers," partly inspired by the Sonic Youth album "Daydream Nation" -- it nonetheless fits a pattern we might call the indie cinema of globalization.

As mainstream movies all over the world melt together into one smirking, ass-kicking blur, independent cinema is also converging, albeit in a much different fashion. Borrowing both from Hollywood genres like the thriller or the western and from the "village film," directors from literally every continent are exploring the bewildering, dislocating and sometimes liberating effects of global culture on isolated provincial life. So "Eureka," with its vision of Kyushu, in rural southwestern Japan, as a society traumatized by sudden violence, uprooted from the past but not quite Westernized, belongs to a tradition that extends far beyond Japan (although Shoei Imamura's "The Eel," an even more mysterious and elegant work in a similar vein, is a good starting point).

In this sense, "Eureka" belongs on a list with Canadian director Atom Egoyan's "The Sweet Hereafter" (and many of his other films), French director Bruno Dumont's extraordinary "The Life of Jesus" and "L'Humanité," Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami's "The Wind Will Carry Us" and almost anything by Senegal's Ousmane Sembène, the founding father of African cinema. "Eureka" even belongs, to stretch the point a little, with some of the wealth of new films from the Chinese-speaking world, like Edward Yang's masterpiece "Yi Yi" or Zhang Yimou's "Not One Less." (Anybody who tries to tell you that world cinema outside the grasp of the Hollywood empire is weak right now hasn't been paying attention.)

All that said, "Eureka" presents a challenge to the viewer, and its American audience is likely to be even smaller than those for the movies listed above (not counting Sembène, who has never had a film in general U.S. release). This is a movie about a bus kidnapping, in which the crime occurs in the first few minutes, mostly off-screen, and the rest of the film consists entirely of the aftermath. Not to mention that it's in black and white, made by a Japanese director you've never heard of and mostly set either in a trashed suburban house or on a bus trip to nowhere whose passengers are variously depressed, psychotic, dying or searching for something they're unlikely to find. And did I point out that you're going to be in your seat for almost four hours?

Still, you can believe -- as I do -- that Aoyama could have shortened his film by up to an hour without sacrificing anything important and still respect the fact that he is clearly obeying his own instincts, his own sense of rhythm. He wants you to live with emotionally shattered bus driver Makoto (Koji Yakusho, who also played the enigmatic hero of "The Eel") and the motley, de facto family group he assembles around him. We watch them fall asleep in front of the TV set and conduct one-sided arguments about octopus dumplings. We learn how thorough Makoto is in washing wet cement off trowels and shovels, and how Japanese bus drivers navigate that country's narrow roadways in reverse gear (with the aid of tiny video cameras on the back of the bus). In the always-controversial task of making the movies seem like life, Aoyama has succeeded brilliantly; like life, his movie will still be here if you doze off or sneak out for coffee or a bathroom break.

Aoyama has made several previous features, although this is the first to gain international attention, and he is most striking as a visual stylist who combines long, spacious takes, grand vistas of unexceptional scenery and surprisingly economical editing. Cinematographer Masaki Tamra shot "Eureka" in black and white on Cinemascope color film, which results in a severe, coffee-stained look to match the film's tone of emotional muteness. I felt differently about this at different points in the film (and I had a lot of time to think about it); as beautiful as much of "Eureka" is in its contemplation of ordinariness, ultimately I think Aoyama seduces himself into a kind of self-indulgence.

When a demented passenger on Makoto's bus pulls a gun, stages a hijacking and begins to shoot the other passengers, we see the action only in unsettling fragments. The final shootout, in which Makoto survives and the bus-jacker (Go Riju, another young Japanese filmmaker) dies, is filmed from a great distance away, as if we were watching a news broadcast from behind the police lines.

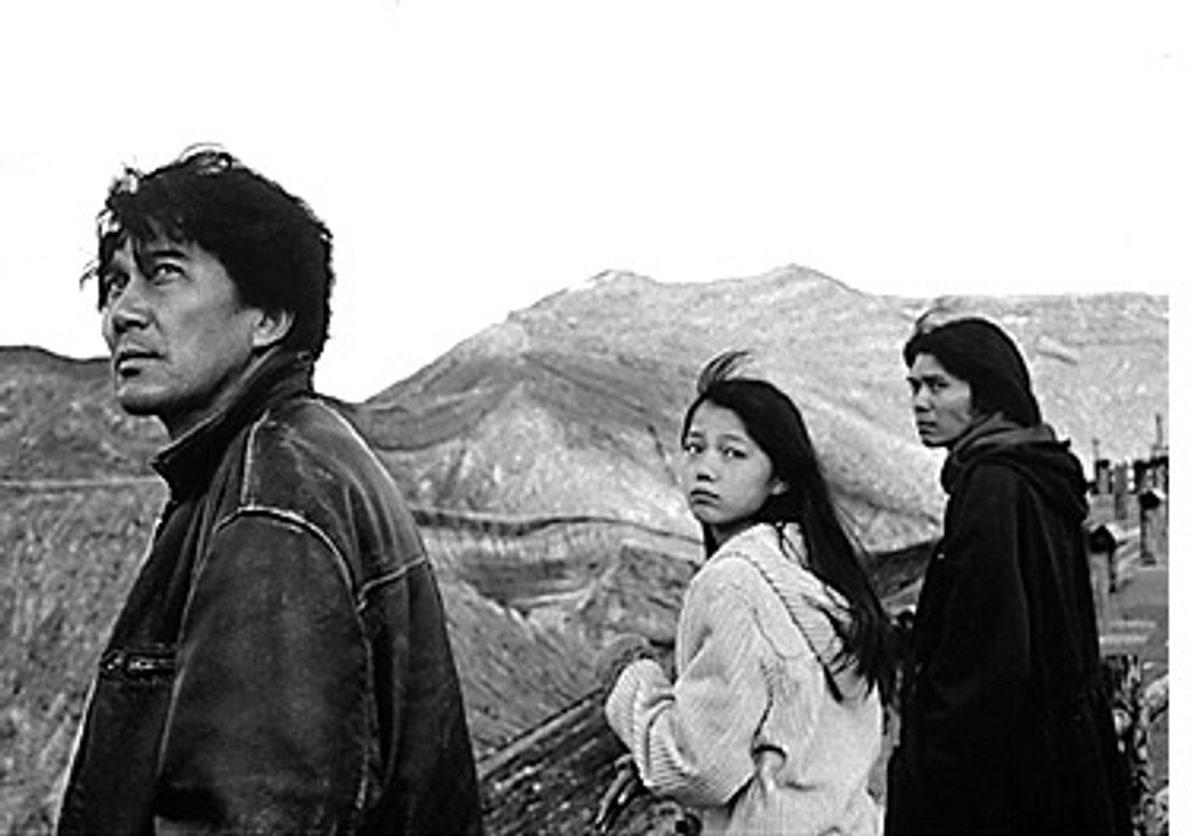

This event, which would be the climax of an ordinary movie, is only the prelude to "Eureka," which picks up again two years later when Makoto, divorced by his wife and thrown out by his family, shows up on the doorstep of Naoki and Kozue (real-life brother and sister Masaru and Aoi Miyazaki), teenage siblings who also survived the hijacking. Although the film's events are presented in a strictly realistic mode, Naoki and Kozue's situation is clearly symbolic: They don't speak, their parents have died or disappeared and they live by themselves in a fussy, Western-style house piled waist-high with dirty dishes and fast-food containers. I have no idea whether this is consciously intended as an allegory about Japan's current predicament, or would strike Japanese audiences that way, but the parallel seemed irresistible to me.

Beneath the leisurely progress of "Eureka" is an ominous undertone that never quite dissipates but also never quite crystallizes on the movie's surface. When we first meet Kozue, she foresees a tidal wave that "will sweep us all away"; Aoyama's camera lingers on the milky sap oozing from the tall weeds around the house after Naoki walks through them, expressionlessly slashing them with a knife. A string of unsolved murders follows Makoto around, and we can only agree with the laconic local police detective (Yutaka Matsushige) who tells him that he is the logical suspect. Only Akihiko (Yoichiroh Saitoh), Naoki and Kozue's jive-talking hipster cousin who has returned from college in Tokyo to look after them, seems free of the film's existential black cloud, but he has his own (rather too formulaic) reasons for joining their impromptu clan.

By the time Makoto buys an old bus and decides to take his foursome on a road trip aimed at exorcising their evil memories, you'll most likely have figured out where they're headed. (It's the same destination as all human voyages, actually.) Still, the delight and the exasperation of "Eureka" come from the same source: its willingness to take its time and explore every detour. Makoto's ex-wife turns up to call him a monster, Akihiko reveals his secrets and briefly adopts a stuffed bunny, two different characters spend time in jail, a beautiful dead woman is apparently reincarnated and Makoto, while suffering from a horrible cough, leads his charges through a blasted volcanic landscape and out the other side into a breathtaking final scene, like some tubercular Virgil. Take off your watch and drink a little coffee (not too much!) and you'll just about make it. You may find yourself spellbound or colossally irritated; it's a close call either way.

Shares