Terry Kinney may be most familiar to moviegoers as Julia Stiles' jazz-musician dad in "Save the Last Dance." But he's been providing movies with genuine, and genuinely eccentric, acting moments for almost a decade now. He had a memorable bit in "Fly Away Home" trying to con a border guard. In "The Firm," as one of the lawyers at a mob-controlled law office, he had an unforgettable reaction to the news of a colleague's murder. Kinney conveyed the character's grief and fear by playing the scene absolutely still, sitting in his backyard, too dazed to notice the lawn sprinkler soaking his expensive suede shoes.

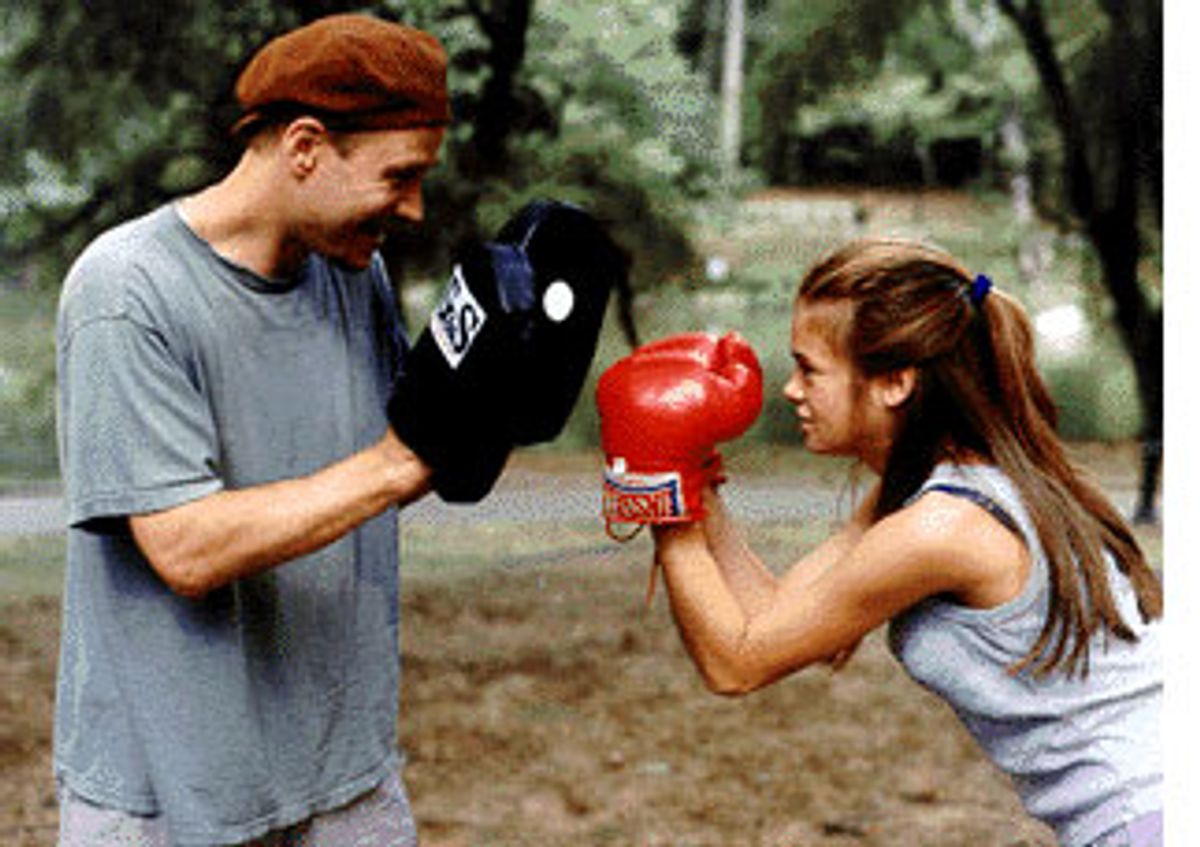

As Hank, a divorced photojournalist dad in James Ryan's "The Young Girl and the Monsoon," Kinney has his first starring role. Tall and lanky with a feathery buzz of hair atop his balding dome and one of those goatees trimmed to perpetually look as if it's about two weeks away from filling in, Kinney walks through the movie with the furrowed-brow look of a worried mutt. He's a man with standards that are not so much exacting as picky and annoying (anyone who's ever lived with a neat freak will mourn for those who share his domicile), and yet he turns his disappointment inward, fretting that he's always about to let somebody down.

It takes until nearly the end for his best moments -- a confessional scene with his 14-year-old daughter (Ellen Muth) in which he reveals that his attentiveness to her was a way to get back at his wife for their failed marriage, and a reconciliation with his young model girlfriend (Mili Avital) in which he manages to play the regret of a man who has let gold pass through his fingers without abasing himself.

They're moments worth waiting for, though until then Kinney is too recessive, too stern. Ryan wants this to be a gently comic portrait of middle-aged confusion and guilt. The problem is that not only does his focus waver (the opening scene leads you to expect that the movie will be from the daughter's point of view) but by presenting Hank's turmoil naturalistically, instead of parodying or exaggerating it, Hank comes off as too much of a pain in the ass.

He's trying to do right by his daughter, Constance, but he's one of those perfectly sensible people whose concern about "permissiveness" causes them to freak out where their kids are concerned. He vetoes the Betsey Johnson gown Constance dreams of wearing to her junior-high prom (does he not notice the way the short shorts and clingy tops she wears show off her cute little figure?) and upbraids her for telling a mildly dirty joke. It's hard to work up much sympathy for a guy who gets huffy simply because a 14-year-old girl is acting like a 14-year-old girl.

And it's hard to empathize with his confusion when he rejects his radiant, open-faced girlfriend, Erin. (Avital is probably best known as the young prostitute Johnny Depp spends some stolen hours with in Jim Jarmusch's "Dead Man"; she's a clearheaded beauty who can act, and why filmmakers aren't clamoring to use her is beyond me.) We can see that he's scared of embarking on another long-term relationship, scared of being rejected by a younger woman. All that's understandable. It doesn't make him less of a schmuck.

Some of the time, I found that my sympathy was more with the teenage Constance, though Ryan never gets below the character's surface. To his credit, however, he hasn't made her charming. Muth is remarkably true to the outward behavior of an impatient, demanding, self-centered teenager who, when it suits her, still wants to act like a little girl. In other words, you want to strangle Constance about half the time. But her gripes and groans are authentic and funny and sometimes refreshing. She's appealing in the way that someone who simply has no time for anything that's boring or uncool can be. (You can almost imagine her growing up to be her father's boss, played by Diane Venora in an attempt at neurotic screwball caricature that's better than the material she's handed.)

This scattershot little movie doesn't have nearly enough going on in it, but every time you're ready to chuck it in, something -- a good line or an actor's moment -- comes along. When Ryan learns more control, and when he picks a subject that will allow him a little more distance, he might develop a pleasing low-key style. His toss-away observations are the best things here -- like the obstinate exasperation of New York street vendors, and the way there's always some civic-minded pill around to ask "Is everything all right?" when you have a public fight with a loved one. And for everyone who remembers slogging through some pointless social studies assignment, Constance's bitching has a point. Aside from Mesopotamians, who cares about the average rainfall in Mesopotamia?

Shares