An ambitious voyage into one of America's darkest and most dangerous realms -- real estate -- "House of Sand and Fog" features an astonishing pair of lead performances and one of this year's most impressive directing debuts. If this movie isn't quite the contempo-Greek tragedy it wants to be, it's still a powerful, unforgettable meditation on fate, cultural collision and the morality of renovating a house that isn't really yours.

That said, it's clear that some people are really going to hate this movie. After the New York screening I attended, a middle-aged couple coming out the door ahead of me were complaining bitterly about all the things they could have been doing instead of watching "House of Sand and Fog." Their list included watching "Law & Order" reruns on TNT or shopping for their kids at Toys 'R Us; it's safe to say these folks were unhappy campers.

Maybe that was entirely their problem. I mean, if they were looking for a feel-good holiday picture that would make them happy to belong to the human race, then director Vadim Perelman's adaptation of the best-selling novel by Andre Dubus III was definitely the wrong choice. But as much of a film masochist as I am (and I've sat through both Herschell Gordon Lewis' "Blood Feast" and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg's "Our Hitler," and in some sense enjoyed them) I kind of want to cut those irritated customers a break. "House of Sand and Fog" is a lot to take, and I'm not sure it entirely justifies the tremendous poleaxing -- the journey from bad to worse to worst of all -- that it delivers the audience before it's all over.

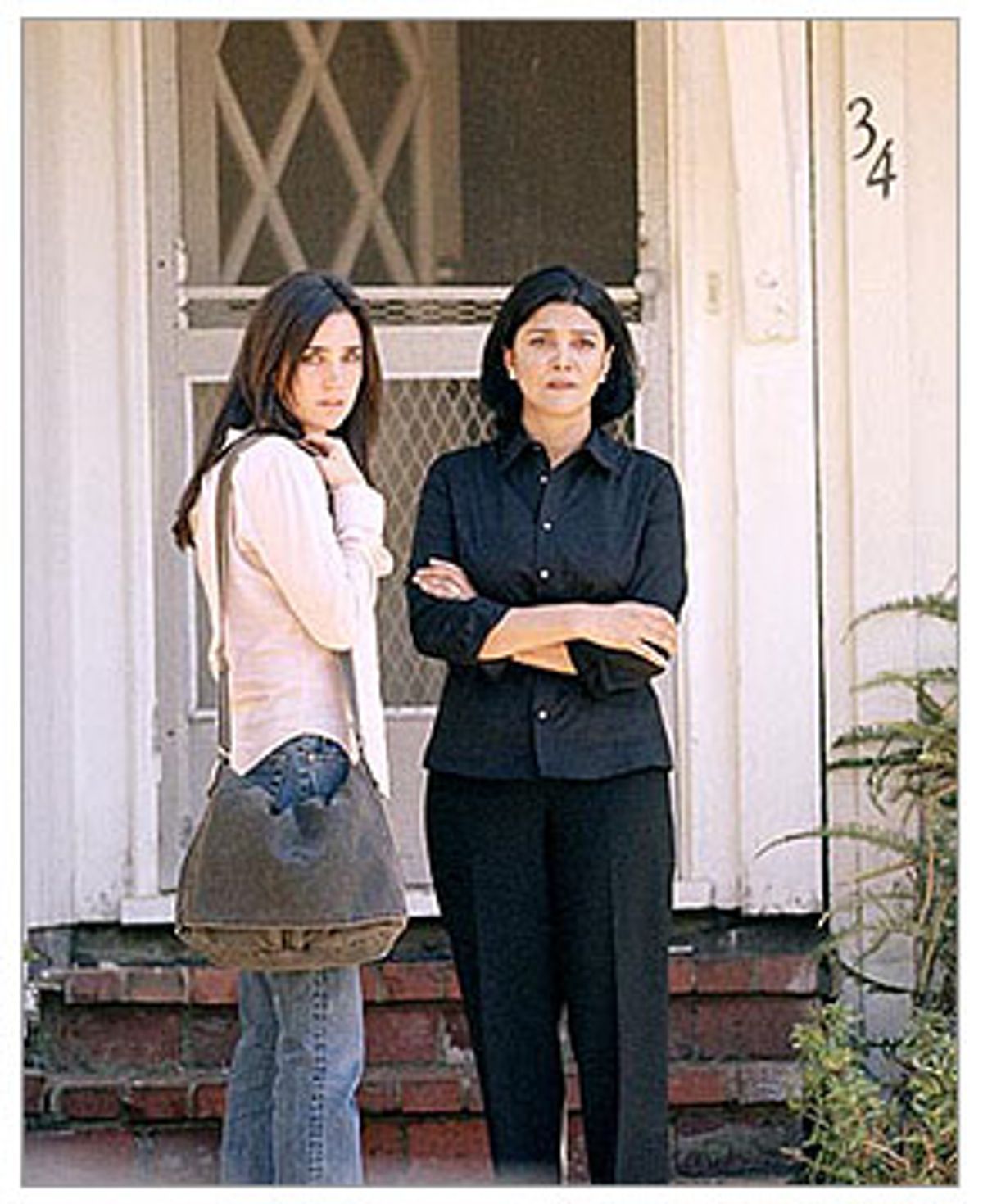

At first, this enigmatic fable about the battle for a dilapidated beach-town bungalow seems to possess the rhythms of a normal Hollywood movie. It's pretty to look at and it starts with one of those immigrant-family wedding scenes moviegoers have seen dozens of times. It has big stars, Oscar winners both, so my enraged friends may have felt comfortable; surely nothing truly awful was going to happen to these characters. Then the sheriff's deputies bust in and wake up depressed, alcoholic Kathy (Jennifer Connelly) to tell her that the house she inherited from her late father has been repossessed and will be sold at auction the next morning. She's out, as in get some cardboard boxes from Safeway and pack your stuff right now.

And that's not the half of it. The other side of this movie's equation is Massoud Behrani (Ben Kingsley), a ramrod-straight former colonel in the Shah's air force who now has his family ensconced in a fancy high-rise apartment in San Francisco. But Behrani's Mercedes-Benz and tailored Italian suits are nothing more than an elaborate facade. Unbeknownst to his wife (Shohreh Aghdashloo) and teenage son (Jonathan Ahdout), Behrani works days in construction and nights at a convenience store, struggling to maintain them in something like the lavish style they've come to expect.

In fact, we first see Behrani in a troubling but unexplained old-country flashback, as he stands on a terrace, wearing his fruit-salad uniform, and watches workmen cut down the pine trees behind his family's former beach house on the Caspian Sea. His wife is horrified at the loss of these stately old trees, and the whole episode is like a muddled premonition of the physical and emotional devastation that is to follow.

Back in the present tense (which is 1991), it turns out that Kathy's house has been seized because of a bureaucratic error -- she is believed to owe $500 in business taxes, but has never actually owned a business. By the time anybody figures that out, the house, which sits on a bluff not quite overlooking the ocean in a fictional Northern California county (the geography is purposefully vague), has already been sold off at a discount price. The buyer, of course, is Behrani, who has been eagerly scouring the classifieds for just such an opportunity and seizes the moment -- as any good immigrant would -- to convert his dwindling savings account into a juicy slice of the American middle-class pie.

Connelly and Kingsley are nothing short of astonishing, and Perelman switches the film's point-of-view -- and the audience's sympathies -- back and forth between them so deftly you're likely to get narrative whiplash. With her freckled, pellucid skin and her bottomless eyes, Connelly is a distractingly beautiful presence; at first I wasn't sure I could believe her as Kathy, who seems to embrace downward mobility with a passion. But this is a subtly impressive performance. Kathy drifts through the movie like a sad, wounded, spoiled ghost, drifting from one deadbeat motel to the next, working housecleaning gigs, all without quite registering the reality of the world around her.

What has happened to Kathy isn't precisely her fault, but she could easily have prevented it -- for example, by responding to some of the delinquency notices that have been piling up among her unopened mail. Her self-destructiveness is bitterly galling, but we never quite believe she's a bad person, and every false step she takes will make you wince. Should she really go out with that beefcake deputy (Ron Eldard) who helped evict her -- the one who's wearing a wedding ring and who likes to drink wine? (Remember, Kathy's a recovering alcoholic.) Should she really start smoking again? Should she really buy a dozen of those little airplane-size bottles of José Cuervo and then go for a long late-night drive? (Well, nobody should do that -- the larger bottles are much more economical.)

On the other hand, Behrani is somebody who has done everything right, without quite managing to do the right thing. Kingsley is justly renowned for his chameleonic ability to play any ethnicity, and here he comes off as the very embodiment of Persian aristocratic pride. He loves his wife and son, and can be tender and generous to them, but does not tolerate any questioning of his authority. His contempt for the laziness and fecklessness of Americans like Kathy -- "They have the eyes of small children, forever looking for the next distraction," Behrani tells his son -- is only worsened by the ignorance and casual racism with which they treat him. Not that he is altogether innocent of such attitudes himself; early on, he rages at his wife: "I did not come to America to work like an Arab! To be treated like an Arab!"

Behrani's pride won't let him smile over the mistake, take his money back and move his family out, and Kathy's combination of wounded arrogance and sheer desperation won't allow her to leave the Behranis alone. By the time Behrani decapitates the top of her house to install a "widow's walk" from which to see the ocean (it's actually a good idea), and Kathy winds up in their bathroom with a nasty puncture wound in her foot and Mrs. Behrani making her tea, "House of Sand and Fog" begins to feel like a comedy of errors that isn't one bit funny.

Perelman and his co-writer, Shawn Lawrence Otto, handle one of the central (and unanswerable) questions of Dubus' novel -- the question of how justice can ever be rendered in such a botched situation -- with great delicacy. As Kathy marvels to her lawyer after her semi-accidental return to the house, the Behranis are "already more at home there than I ever was." In his autocratic, often maddening fashion, Behrani has invested this ramshackle house with something very much like love, an emotion of which Kathy seems frankly incapable -- but the fact remains that his ownership of the place is only a fluke of fate.

As "House of Sand and Fog" grinds toward a devastating collision, the careful balance between its characters finally falls apart. On one hand we have Kingsley, the luminous Aghdashloo (a grande dame of the Iranian expatriate community) and the sweet and serious Ahdout, a family that for all its old-fashioned sexism and dysfunction is based, at least in theory, on dignity, love and mutual respect. On the other, we have Kathy, spiraling back into the bottle and clinging -- because she has nothing else -- to the demented schemes of Eldard's unhappily married deputy, who's as bent on self-destruction as she is. I guess his character is supposed to be a cipher, but the part is undercooked to the point of rawness, and Eldard's male-model blankness makes him seem more like a leftover cyborg from "Terminator 3" than a plausible loose-cannon cop.

Memorably photographed by Roger Deakins, one of our era's great cinematographers, "House of Sand and Fog" is a dizzying, nightmarish plunge into the atavistic cruelty that lies beneath the surface of everyday American life. The house of sand and fog in Dubus' title is not that perky little bungalow with the crooked shades but the nation whose ideology of mutual self-interest (and whose bureaucratized, impersonal society) creates disasters like this one. For Vadim Perelman, this marks the beginning of an auspicious career. Ben Kingsley is likely to rack up more awards nominations, and if Connelly doesn't follow suit, it's only because her role isn't as showy. But for some moviegoers -- most, actually -- reruns or Toys 'R Us might be a safer bet.

Shares