In Zhang Yimou's 1999 film "The Road Home" a poster for the movie "Titanic" hangs on the wall of an elderly widow's modest home in a rural Chinese village. Even given the worldwide pervasiveness of American pop culture, the passing detail of that poster is startling. You wonder, has the old lady seen the movie? Where? Does one of her neighbors have a VCR? Do movies play in some communal hall in her village? And where did the posters (there are two, actually) come from?

Zhang isn't using the detail to lament the popularity of American culture (though the success of a stinker like "Titanic" is depressing), and I'm not much interested in doing that either. Froth all you want about cultural hegemony, but proposals like the French one of a few years back to limit the number of American movies imported into that country have obvious flaws. Apart from the ugly prospect of censorship (what else do you call a government deciding to withhold certain films from distribution?), the people behind those proposals always conveniently ignore the millions of others who want to see American movies. I'd much prefer it if more people in France (and in America) saw Philippe de Broca's "On Guard!" than "Troy." I just don't think the decision should be made for them.

But I do wish things worked in reverse as well. American culture is unavoidable worldwide, but in the U.S., the pop culture of other countries is almost totally avoidable. Every forgotten Broadway performer who once had a second lead in "Hello, Dolly!" merits an obit in the New York Times, but it took the paper a week and a half to acknowledge the death of Hong Kong pop star and actress Anita Mui. Try to imagine the Hong Kong press waiting that long to acknowledge the passing of Madonna -- because that's the equivalent.

It would be easy to blame that resistance to foreign culture completely on American provincialism. But most people, no matter where they're from, respond more instinctively to their own culture. There's no language barrier, for one thing, and there's a shared pool of references and tradition and convention.

Foreign influences have the damnedest way of working their way into American culture. "The Matrix," for example, is unthinkable without Hong Kong movies (or the New Testament, for that matter). And Middle Eastern rhythms have steadily been making themselves felt in hip-hop.

Still, in the U.S., foreign pop remains a specialized acquisition. Americans who get caught up in some aspect of another country's pop culture are often looking for something they feel is lacking in their native pop. Action-movie aficionados become connoisseurs of Hong Kong movies. Comic book fans may find themselves captivated by manga. (I fell for French pop after I saw Françoise Hardy singing in a 1960s promotional clip on MTV.)

A natural feeling of protectiveness may come over us when we discover a singer or a writer or a movie that only a few other people know about, whether in our own culture or another. The impulse to keep it our cherished secret is understandable, but it goes against the expansiveness of pop culture and the very idea of being a fan: the impulse to spread the word about your discovered passions.

Too often, an unshared enthusiasm -- particularly when it comes to foreign pop -- becomes a p.c. way of trumpeting your superiority. (In movies, that's always been typified by the art-house dandies who wouldn't be caught dead at the multiplex.) The challenge for a critic who champions the pop culture of another country is both to capture what makes it distinctive (and refreshingly different from what we are used to) while also talking about what makes it accessible to audiences beyond its borders.

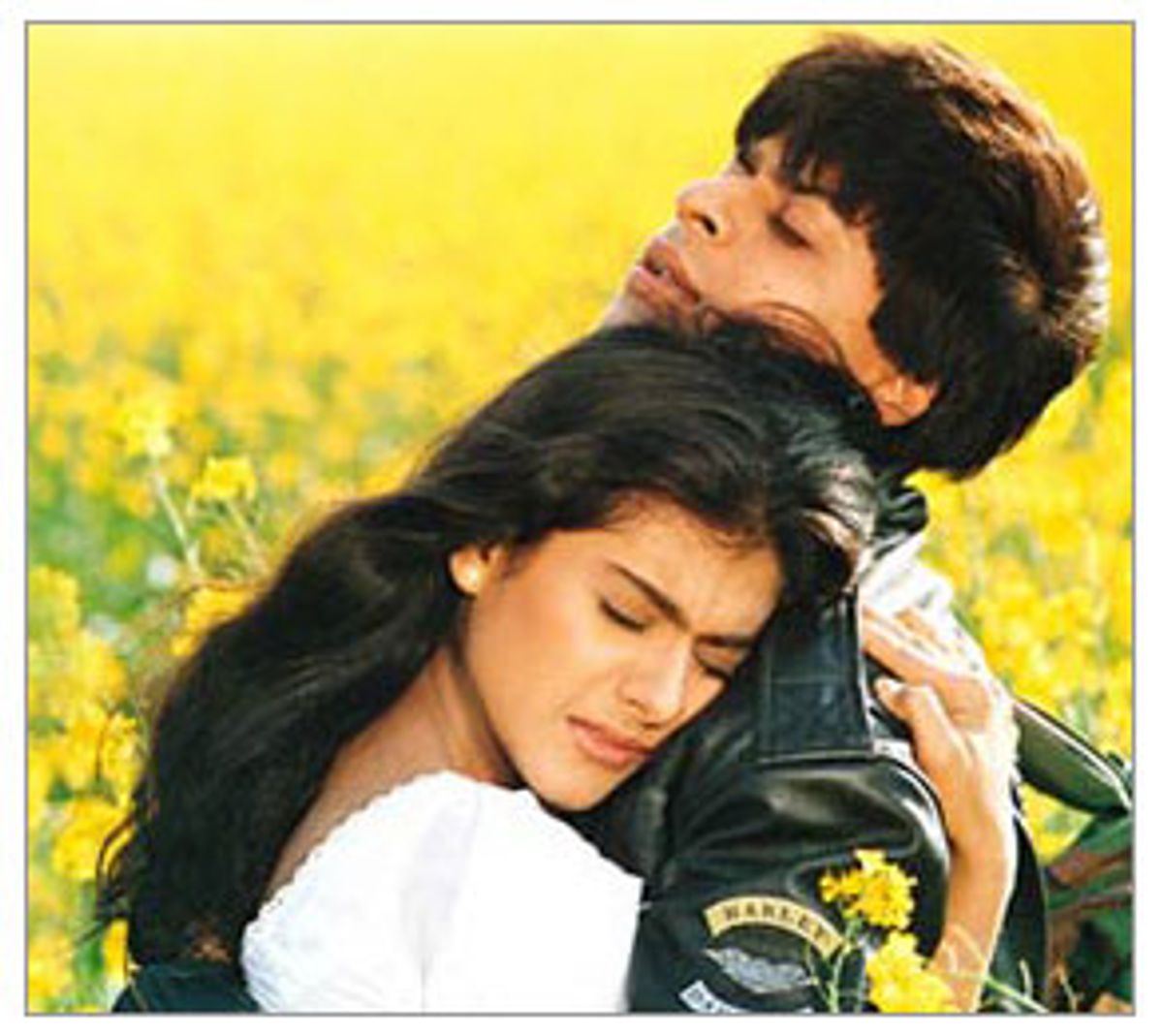

The 1995 Bollywood musical "Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge" ("The Braveheart Will Take the Bride"), the debut film from then 24-year-old director Aditya Chopra, is one of those pieces of pop culture that easily traverses borders. The movie is touring the U.S. through August as part of the Cinema India showcase "The Changing Face of Indian Cinema." (It's also available on DVD.) Released in the same year as "Titanic," "DDLJ" (as it's known to its fans) has had the longest continuous commercial run of any picture in the history of Indian cinema. It opened in October 1995 and as of 2002 (the year Indian film critic Anupama Chopra's smart and useful monograph on the movie appeared) it was still packing a thousand-seat movie palace in Bombay.

"DDLJ" is one of the most successful films in the history of the world's largest film industry. And if you're an American outside of the country's Indian communities, chances are you've never heard of it. Bollywood films get no commercial release in the U.S. and yet the fact that "DDLJ" is unknown is still strange. This is a picture that should be part of our shared experience of movies. It offers the large, unsubtle, overwhelming satisfaction of the best popular entertainment. It's a flawed, contradictory movie -- aggressive and tender, stiff and graceful, clichéd and fresh, sophisticated and naive, traditional and modern. It's also, I think, a classic.

Chopra has no compunction about indulging in clichés and conventions. He allows his actors to mug shamelessly, and he employs sudden spikes of music like an unwelcome jab in the ribs to underscore the movie's dramatic revelations. Yet he's been blessed with the ability to transcend cliché. You can laugh when the hero, Raj (Shah Rukh Khan), picks up a wounded dove and heals it by rubbing it with the soil of his native Punjab. Or you can be moved by the conviction in the moment, the love Chopra reveals for India in the scene, and his braveness in not worrying about whether the scene was realistic (it isn't -- so what?). Chopra is that rare mix in a popular entertainer, both shrewd showman and true believer. (And apparently, something of an eccentric. According to Anupama Chopra -- no relation -- he gives no interviews and refuses to allow himself to be photographed, believing that if he loses the ability to attend movies anonymously with a regular audience, he will lose his ability to make movies for them.)

At 189 minutes, a length that audiences for Bollywood films are used to, "DDLJ" may seem long to Western moviegoers (though I wasn't bored for a minute). And, for roughly the first 70 minutes, the movie is unaccountably broad (Shah Rukh Khan, who settles down in the second half, sometimes seems the offspring of John Stamos and Jerry Lewis). Throughout the movie, the interiors sometimes have the anonymous flatness of the deadest Hollywood movies of the '50s and '60s. But even during the uncertain patches, Chopra reveals himself to be a whiz at the expressive use of color and landscape. (It's a pity that the DVD transfer renders some scenes dark, depriving the colors in Manmohan Singh's cinematography of the brightness they have on-screen.) The opening scene contains a lovely cut from the heroine's father feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square and speaking of his longing for his homeland to him feeding the birds in Punjab while dancers with colorful silk veils emerge out of mustard fields behind him.

You can laugh at the stylization of a touch like that (although if "realism" is your standard of achievement, why are you going to the movies?). Audiences who are used to classic Hollywood musicals may have trouble getting used to their Bollywood equivalents. The song-and-dance numbers jump from place to place and even season to season while the performers go through four or five costume changes in the course of one song. The rhythms are created by the camera movements and the need to take in the picture-postcard background, rather than by the movement of the dancers' bodies. Hollywood has taught us that the best way of shooting a musical number is to show the dancers from head to toe without cutting away. Often it is -- if you're looking at Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly or Michael Kidd or Gregory Hines. The numbers in "DDLJ" aren't of that type; there's something refreshing about the artificiality of Bollywood style. For one thing, it's an implicit refutation of that idiot notion that song and dance should grow "organically" out of the story. (Why -- so we can have more dreck like "Oklahoma!"?) And in the case of "DDLJ," the numbers are so colorful, and the songs (by the brothers Jatin and Lalit Pundit, who work as Jatin-Lalit, and Anand Bakshi) are so catchy, that you'd have to be a bit of a stiff to resist them.

None of this is to suggest that, for Western audiences, "DDLJ" is enjoyable chiefly as a novelty. The key to the film's power and to the enormous satisfaction that it gives is that it has behind it both the traditions of popular movies and the traditions of Indian culture. I'm no expert on that culture, but I don't think you have to be to feel Chopra's deep respect for tradition, though with its connotations of something musty and antiquated, "tradition" might be a misleading word. Tradition is a living thing in "DDLJ." The characters feel the weight of its presence in every moment of their lives. Chopra's accomplishment here is to show, simultaneously, how that link to tradition strengthens them and how it comes close to suffocating them.

"DDLJ" is essentially a simple story of lovers overcoming obstacles to be together. Simran (Kajol) is the oldest daughter of Baldev (Amrish Puri), a Punjabi shopkeeper who has lived in London for 20 years but longs for home. Raj (Shah Rukh Khan) is the wastrel son of a happily assimilated millionaire (Anupam Kher). The two meet when they each take a Eurail trip around the continent with their friends. At first Simran can't stand the joker Raj, which, in the conventions of romantic movies, tells us that they are perfect for each other. By the end of the trip, they've fallen in love -- without quite admitting it to each other. The trouble is that Simran is engaged to a man she's never met, the son of Baldev's boyhood friend, as the result of a pact Baldev made with his friend years before to bind their families together. When Baldev hears Simran confessing to her mother, Lajjo (Farida Jalal), that she's finally found the man she dreamed of, he fears his daughter has become too used to Western ways and immediately moves the family back to Punjab so that Simran's wedding can take place.

It's here, according to Anupama Chopra (in her book published as part of the British Film Institute's BFI Modern Classics series), that Aditya Chopra broke with a major convention of Bollywood films. Instead of eloping with Simran (as in the traditional Bollywood move), Raj tells her he will not marry her until her father himself gives him her hand. He follows Simran to her family's Punjabi village, insinuates himself into the household of her bridegroom-to-be and, without seeming to do much more than being charming and trusting to fate, realizes his dream.

"DDLJ" should be completely accessible to Western audiences, particularly to audiences raised on classic Hollywood movies. They both, in essence, represent traditional art. The great strength of art that's traditional in both the form it takes and in the values it espouses is that it gives weight to the challenges that arise to those values. In his brilliant essay on the Anglo-Bangladeshi novelist Monica Ali's "Brick Lane" (included in his new collection "The Irresponsible Self") the literary critic James Wood writes, "Traditional societies, with their ties of marriage, burdens of religion, obligations of civic duty, and pressures of propriety [restore] to the novel form some of the old oppressions that it was created to comprehend and to resist and in some measure to escape."

Essentially, Wood is saying that rebellion is not possible unless there's something to rebel against. On a subtler level, he's acknowledging that most of us are not rebels and that, in novels and movies, the burdens of traditions that are foreign come to seem a stand-in for the responsibilities we're burdened with, responsibilities we may dream of escaping even as they form an inextricable part of what we are. And it is the inescapable duty those responsibilities entail that give our longings the disruptive power they hold over us.

"DDLJ" doesn't have the depth or the subtlety that Wood finds in "Brick Lane." But it shares with Ali's novel and with Jhumpa Lahiri's fiction an awareness of the poignance of the diaspora -- the simultaneous longing for the reassurance and continuity of tradition and for the freedom of the new world. Anupama Chopra points out that the assimilated Indian has long been a stock villain in Bollywood films, held up as proof of the corrupting influence awaiting outside Mother India. Aditya Chopra's sly switch is to make Raj, living the life of a spoiled rich kid in London, a rascal with deep respect for Indian tradition and to make Simran's fiancé Kuljeet (Parmit Sethi), the Indian who has never left home, the villain. Chopra overdoes it. Kuljeet is a leering bully who plans to keep Simran at home while he travels to London and samples the girls there. But the point is made: No culture offers a guarantee against corruption.

"DDLJ" is about how the lovers balance the responsibilities to family and tradition with the longing they feel for each other. You could say that by devising a solution that satisfies both tradition and romance, Aditya Chopra is trying to be all things to all people. But reaching for a broad audience is not the same thing as kowtowing to a focus group. To satisfy a wide audience, you have to have breadth, daring and confidence. Chopra pulls off something incredibly tricky in "DDLJ." Within the most idealized of contexts -- the movie musical -- Chopra insists on the unidealistic truth that life is never one thing or the other. He finds a way to honor romance while acknowledging the compromises that life inevitably demands.

Presumably, the Indian audiences who have flocked to the movie have had no trouble understanding what Chopra was up to. But audiences we think of as educated (or at least who think of themselves that way) often have a problem getting beneath the surface of movies that don't dismiss tradition or social niceties they have no use for. That's what happened when I saw "DDLJ" a few weeks back, when it was shown at the American Museum of the Moving Image in Queens as part of the Cinema India showcase. In one sequence, Simran and Raj get separated from the friends they are traveling through Europe with and have to share a room for the night (I warned you Chopra has no compunction about using old convention). The next morning, Raj momentarily fools her into thinking they've made love. Completely distraught and believing she's been "ruined," Simran must be comforted by Raj who tells her, "I'm not scum. I'm Hindustani. And I know what honor means to the Hindustani woman." Late in the film, when it appears that Raj will lose Simran to her arranged marriage, Shah Rukh Khan delivers an impassioned speech where he tells Simran they must obey her father. "All our lives, they [our parents] have brought us up," he says. "They gave us so much love. About our lives, they can decide better than we can. We have no right to make them sad for the sake of our happiness."

At AMMI, the largely white, presumably liberal audience hooted at those scenes. It was as blatant an example of Ugly Americanism as I've ever encountered at the movies. The audience, which would have blanched at someone laughing at, say, a Kabuki performance or at the opera, had to make its little show of demonstrating that these values were not their values. If they had been just a trifle more observant, they might have had reason to question whether they were even the values of the movie they were watching.

On one level, of course they are. But Chopra never lets us forget the price tradition extracts. Because it deals with heightened emotion, romantic melodrama has often been described -- and derided -- as a woman's genre. But melodrama has often served to express women's experience, and because melodrama is essentially aggressive (which is what gives the form its redeeming honesty), it has expressed that experience forcefully. Throughout "DDLJ" tradition blinds men to the emotions of the women they love. Simran finds out about her engagement when her father gives her a letter from his friend. Reading it, she learns she is to be married to a man she's never seen; she runs out of the room in tears. Baldev's reaction is pride that his daughter is still modest. He literally does not see the tears, just as he doesn't see (or pretends not to see) how distracted and unhappy Simran is when the family returns to Punjab. It's Baldev's elderly mother who notices Simran's unhappiness and points it out to her son, who dismisses it.

The movie's most extraordinary moment -- and I think one of the most extraordinary moments I've ever seen in a popular movie -- is a scene between Simran and her mother. It's one of those scenes, like the scene in "The Best Years of Our Lives" where Teresa Wright announces to her parents that she's fallen in love with a married man and intends to break his marriage up, where a traditional work suddenly gives expression to feelings that threaten to smash tradition to the ground. And because those feelings appear in the context of a mainstream movie, they seem riskier, more daring. (Works for specialty audiences rarely threaten that audience's entire value system in the way that a mainstream work can.)

Lajjo finds Simran sitting by the window in her bedroom. We hear a lonely sound of wind whistling through the trees and, when the camera moves around, a painted backdrop of trees against the blush of an evening sky. Lajjo tells her daughter about her own childhood, how her father told her that women have the same rights as men. And she talks about how that promise was denied her at every turn, how she was expected to sacrifice her own happiness again and again as a sister, a daughter, a wife and a mother.

Simran, who has been gazing out the window, averting her eyes from what she has every reason to expect will be a speech about how she must do her duty, is suddenly startled enough to turn her eyes to her mother. This is a woman she has described to Raj as more like a friend than a mother, and yet the expression on Simran's face (Kajol doesn't utter a word in this sequence -- she doesn't need to) tells you she's never heard Lajjo talk like this, has never even imagined she would.

"Once you were born," her mother continues, "when I held you in my arms for the first time, I made a promise, never to let happen to my daughter what happened to me." A flicker of hope enters Simran's eyes -- which makes what follows all the crueler. "I had forgotten," her mother tells her, "that a woman hasn't even the right to make promises. She is born to be sacrificed for men. For their women, men will never make sacrifices." And she follows this with an even more amazing line: "Therefore I, your mother, come to take from you your own happiness."

The power of the scene isn't in spite of the melodrama but because of it. The heightened, even "corny" (a phrase I detest) cadences of the language intensify the emotion so that Lajjo's bruising candor takes your breath away. There's a horrible irony at work in the scene. Lajjo talks to Simran as the friend Simran always described her as; who can imagine a mother offering such a bleak future to her own child? And just when you think the scene can't go any further, Lajjo delivers one of the most damning lines any spouse has ever spoken about another on-screen: "Your father won't care for your tears."

Of course, Baldev has to learn to care for Simran's tears, and he holds on to his daughter by -- literally -- letting go of her. To pull that off, you have to have not just breadth -- the confidence that you can meld two contradictory impulses into a seamless whole -- but generosity. You have to be willing to allow, as Aditya Chopra is, that a character like Baldev, who comes close to being the movie's villain, has the capacity to change. There's a flash of this in an earlier scene, a musical number during the celebration of Simran's engagement. Lajjo has joined the dancers and suddenly the crowd parts to reveal Baldev standing there watching her. Everyone freezes, expecting him to chastise his wife for making a spectacle of herself. She starts to move off the dance floor and is stopped by her husband singing, "O my precious one ... I could still die for you my love." You can call it obvious, but it's these obvious moments, full of unexpected, expansive emotion that we go to the movies for. Like everything else in "DDLJ" it's a simple gesture given weight by the bigness of the emotion and the CinemaScope screen.

I'm not giving anything away by revealing that Raj and Simran wind up together. The beauty of Chopra's conception is that we are watching a myriad of unions. It isn't just the hero and heroine who are wed, it's male prerogative and female persistence, tradition and innovation, the home and the world.

Shares