The closest thing to entering a dream state at the movies right now is watching "Last Life in the Universe," the fourth feature from Thai director Pen-Ek Ratanaruang. The rhythms of the film are so lulling (which is not a synonym for boring) that when Pen-Ek pulled the Buñuelian trick of substituting one actress for another in the midst of a scene, it took me a minute to register the switch.

What's on screen is seamless -- the muted palette that master cinematographer Christopher Doyle employs, the unobtrusive precision of his framing (a shot of a rose and an extension lamp suggests the sort of still-life Pierre Bonnard might have done had he been forced to live in the age of modernist, minimalist design), the wave-lapping shifts of Patamanadda Yukol's editing, the barely there score, by Small Room and Hualongpong Riddim, that feels as if it were drifting in from an open window. Walking into "Last Life in the Universe" off the hot summer streets, you enter a relaxed, alert state.

I'm damned if I can say what "Last Life in the Universe" is, aside from a melancholy, deadpan comedy about the irony of fate and how living in the world entails emotional messiness. When a director refuses to force the meaning of scenes, or even the performances of his actors, it's easy to feel as if you're missing something. Perhaps Pen-Ek is too subtle at times. But "Last Life in the Universe" didn't make me restless or impatient. The movie is a lovely thing. Even when violence disturbs the quietness, it doesn't feel as if leaden irony has entered the picture. It's perfectly natural here for a yakuza, stepping over the body of a man he has just killed, to say "Excuse me."

It seems to take forever before we get a look at the face of Kenji, played by Tadanobu Asano, the star of Takashi Miike's notorious cult hit "Ichi the Killer" (Miike himself shows up as a yakuza boss). Kenji is a young Japanese librarian living in Bangkok. His mop of hair hangs down over his features, giving him the air of a turtle trying to withdraw into his shell. There's a careful precision to Kenji's polite interactions with his boss, and especially to his immaculate apartment done in shades of off-white and gunmetal gray. Putting a six-pack of beer into the fridge, Kenji makes sure to line up the cans perfectly and turn the labels to the outside. The chaos Kenji is holding at bay is suggested by his frequent flirtation with suicide (in the opening scene, he hangs a noose from the ceiling and leaves a suicide note reading "This is bliss") and the sudden appearance of his gangster brother. When this guy shows up, you know it's only a matter of time before Kenji's ordered life will be shot to hell.

When it is, he winds up on the outskirts of the city, sharing the house of Noi (Sinitta Boonyasak), a girl whose sister has just been killed in a car accident. If Kenji's apartment is a neatnik's dream, this place is the nightmare. Magazines and DVDs spill across the floor, the sink overflows with dirty, food-encrusted dishes, detritus of all sort litters the floor. And still Kenji stays there, he and Noi establishing a tentative rapport, because he can't return to his own life.

The contrast Pen-Ek sets up should be obvious from that description -- Noi represents the chaos of life that Kenji has tried to escape. Essentially, it's a screwball-comedy setup. Noi is the kook who brings a repressed man back to the world. Pen-Ek doesn't use the conventions of a genre here as much as he evokes the ghost of a genre. He did something similar in his previous film, "Mon-rak Transistor," a musical about the travails of a country boy in the bad city. At times, watching it felt like seeing some forgotten '30s Hollywood musical that was being simultaneously translated into a foreign language.

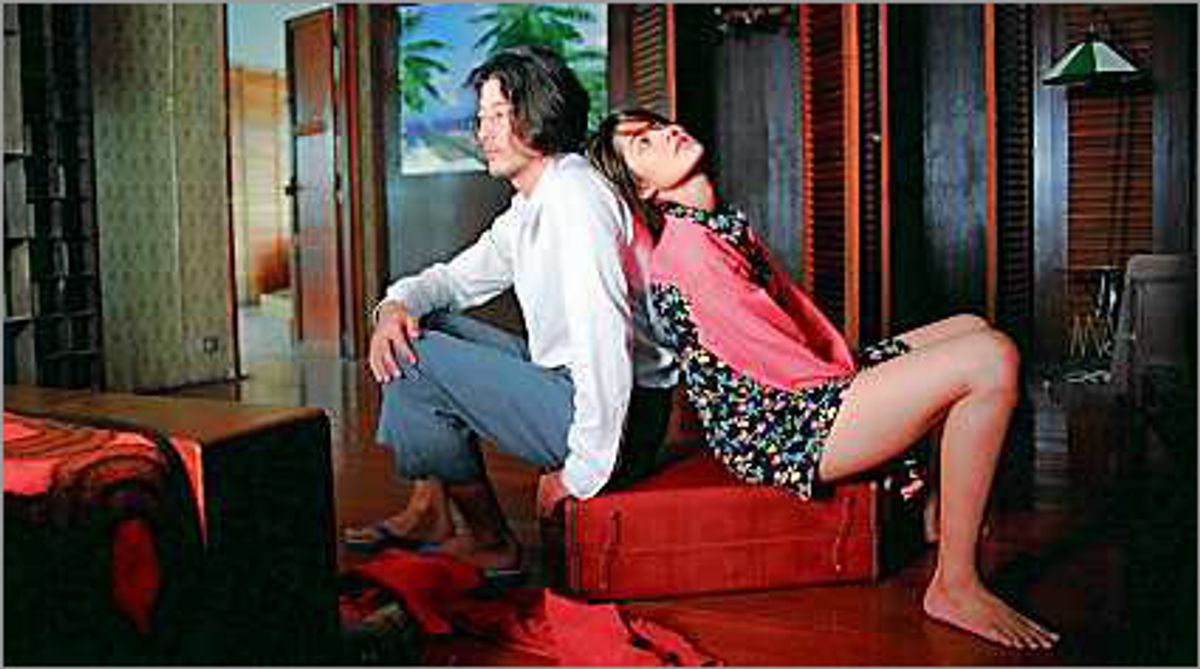

But "Last Life in the Universe" isn't tied to any rules. There's nothing predictable or programmatic about the way the movie proceeds. Kenji isn't an object of derision for the movie, the way the uptight male heroes of screwball comedy are. He isn't forced back into the world. He's left to disturb the waters slowly, one toe at a time. And Noi isn't totally the life-force free spirit. She's a bit of an aimless soul, clamping down the grief she feels over the loss of her sister in the waspishness that comes over her from time to time. Yes, they're a mismatch, the neat freak and the girl who can't be bothered to pick up her shoes. But I've known marriages that work from pairings like that. Asano and Sinitta manage to give delicate performances while providing enough weight so that there's something at stake in whether these two will get together.

I don't want to say any more about the specifics of "Last Life in the Universe," the turns of plot, the way Pen-Ek plays with the intermingling of desire and reality, the small, resonant ironies that really are ironies and not just cheap cynicism, a scene that plays like an unexpected homage to "Mary Poppins." Much of the pleasure of the movie is the way its mood lingers with you afterward. From the manner in which "Last Life in the Universe" feels its way along, Pen-Ek might seem a quirky filmmaker, not one to get excited about. Who knows yet if he has a large-scale vision? But he's an original, and original in a way that doesn't suggest affectation. You might have to fiddle your dials a bit to tune into his wavelength but what comes through the occasional ebbing of the signal is a melody worth hearing.

Shares