"The Aristocrats," Paul Provenza and Penn Jillette's exhilarating documentary about the genesis and continual evolution of one very dirty joke, is less about free speech than about the freedom of speech. And viewing it as a manifesto only detracts from its indelicate, yet delicately calibrated, brilliance. It doesn't matter that AMC has opted not to run the movie in its theaters: That's not censorship but a business decision. (Everyone has the constitutional right to be a numbnuts.) Nor is it particularly meaningful that conservative critic Michael Medved has sniffed derisively at the picture, like a dog who thinks it's above the smell of its own shit. The inherent offensiveness of the joke itself (more on this later) is the controversial sticking point. But the picture itself is so ebullient and celebratory that it practically beams with perverted innocence. It also moves with an acrobat's timing. (I've seen French art house movies that aren't nearly so beautifully made.) All of this is a roundabout way of saying that unlike Medved, I know art when I smell it, and "The Aristocrats" is it.

The joke at the heart of "The Aristocrats" is an in joke among comedians, one they've historically told among themselves but never (at least until recently) in public performance. As at least one of the some 100 stand-up comics featured in the film puts it, the joke is a kind of secret-society handshake, a way for comedians to get laughs from their colleagues, the toughest crowd they'll ever face. The joke is also, as Provenza says in the movie's press notes, "the comedy equivalent of jazz": Like a jazz standard, it's a gag with a predefined structure, or melody, that holds a universe of possibilities for improvisation.

The melody goes something like this: A guy walks into a talent agent's office and launches into a detailed account of his act, which involves himself, his wife and his kids, as well as, possibly, any number of family pets and assorted clever props. (Aunts and uncles, grandpas and grandmas, often join in the fun too.) The description of the act is the body of the joke, a transgressive shaggy dog story that may include, but is by no means limited to, lewd sexual acts of all sorts (incest, bestiality, you name it), plus blood and other types of bodily goo, and, ideally, a great deal of slippery, slidey shit and piss. The object of the joke is to come up with the filthiest, most offensive, most imaginative details possible. The booking agent listens to the windup and asks, in disbelief, "What do you call that act?" thus setting up the punch line: "The Aristocrats!"

While you do need a high tolerance for toilet humor and verbal filth to enjoy "The Aristocrats," whether you find this half oblique, half grapefruit-in-the-face joke funny is beside the point. "The Aristocrats" is an extended riff on an extended riff, a glimpse at the lengths to which stand-up comedians will go to amuse one another. It's also, as any smart anthropologist would tell you, an exploration of the ways populations share stories ("And then Grandma comes out and has an abortion onstage!") and anecdotes ("Pops has taken plenty of laxatives beforehand, so everything is really loose") to affirm their identities. Or, as Jillette so eloquently puts it, "In all of art, it's the singer, not the song."

What's amazing about "The Aristocrats" -- both the joke and the movie -- isn't so much what's in it as how that intentionally offensive content is spun out for the audience's pleasure. Some of the comics featured in the movie tell their versions of the joke (Dana Gould has an Amish interpretation that's particularly ridiculous; Mario Cantone tells it as Liza Minnelli describing her new act, which will begin with her fitting an entire piano up her vagina), while others just ruminate on the pros and cons of its mere existence. Some, like stately snapping turtle Pat Cooper, don't exactly respect the joke, but you can tell they harbor a grudging affection for it. A few, like Eddie Izzard, don't get it at all (fascinating in itself because the "melody" of the aristocrats joke is the very thing that allows other, perhaps more literal-minded, comedians to do the kind of free-form dada that's Izzard's stock in trade). Others, like the exquisitely deadpan Richard Lewis, state outright that the joke is a "piece of shit," and yet, as Lewis gazes soulfully into the camera, we realize that we don't know whether to buy the words coming out of his mouth or the gleam of mischievous appreciation we see in his eyes.

Comics are drawn to the joke like moths to a naked flame, and Provenza and Jillette capture as many outlandish variations of it as possible. George Carlin tells the first complete version of the joke we hear in the film, an opera of scatological intensity and magnificence; "Full House" star Bob Saget tells a version that gets so horrifically grisly in its details that it made me queasy; Drew Carey, that handsome, barrel-chested lug of a guy, adds a dainty, flamenco-style finger snap to his version; Jillette appears with his stage partner, the quizzical imp Teller, whose silent shock and dismay at Jillette's explication of the joke becomes its real punch line; and Eric Mead performs an astonishing version that uses card-trick sleight of hand as a visual aid.

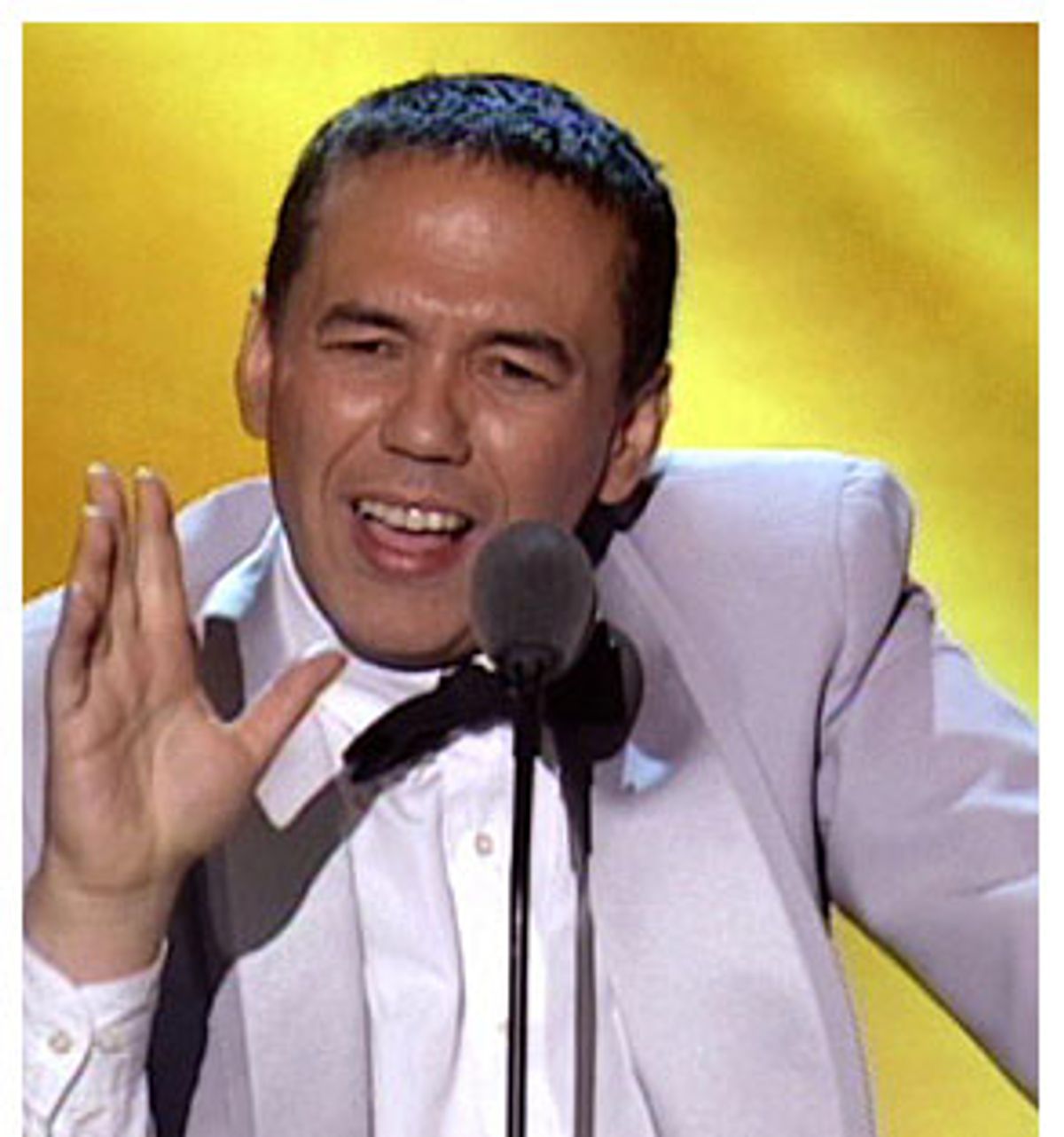

But the movie's centerpiece is the footage of Gilbert Gottfried telling the joke -- perhaps the first time it has ever been told in front of a civilian audience -- at the Friars Club roast (the guest of honor was Hugh Hefner) held in New York a few weeks after Sept. 11. Just before unleashing the joke on his unsuspecting audience, Gottfried had tried a gag about how his flight back to Los Angeles had been rerouted through the Empire State Building; the audience, not yet ready for 9/11-themed humor, booed him. So Gottfried, in a sharp turnaround that amounts to nothing short of comic genius, decided to switch gears and assault them with the filthiest joke they'd never heard. His staccato, crisply enunciated, ear-splittingly nasal delivery turns the joke into a kind of "Mona Lisa" of perfection. (Rob Schneider is clearly visible in the footage, literally tumbling off his chair. In fact, he can't seem to stay in it: He simply keeps falling off it.)

Gottfried's stunt has become the stuff of legend among his colleagues: They're in awe of it, they respect him for it, and, most of all, they find it howlingly funny. "The Aristocrats" opens a secret window into the world of stand-up comics -- into how they relate to one another and compete with one another, but also into how they themselves are never quite sure about what makes a bit funny. With "The Aristocrats," Provenza and Jillette blow the lid off what is perhaps the greatest shared joke among comedians, while respectfully preserving the mystery of what makes the joke -- or any joke -- work. The aristocrats joke is funny because it pushes the limits of what we think we should allow ourselves to laugh at, but beyond that, it defies analysis. Sometimes the profane is sacred.

Shares