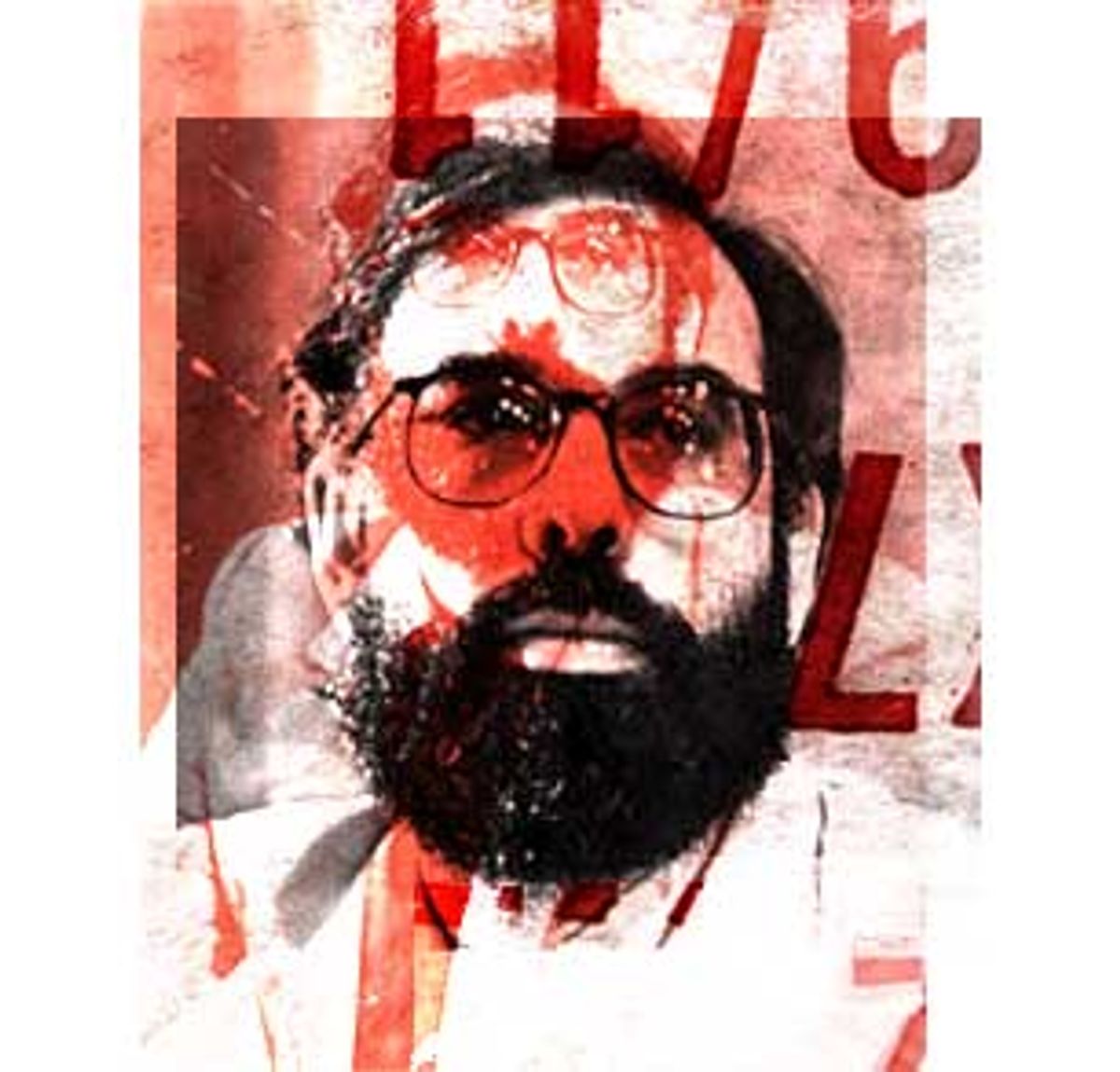

The best glimpse you can get of Francis Ford Coppola comes in

"Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," a 1991 documentary about

"Apocalypse Now" that draws on his wife Eleanor Coppola's film and audio

recordings during the shooting of the movie (in 1976 and '77) and her

marvelous 1979 book, "Notes." Whether you view him as a tortured poet, an

ostentatious showman, a martyr or an ogre, it's impossible not to get caught

up in his drive to overcome disasters -- natural, political and theatrical

-- and to push his movie to the finish line.

No matter how desperate his

statements, no matter how eccentric his MO, he's vastly more engaging than

the average precocious millionaire (he was, at the time, in his late 30s).

He's going all out for art, and persuading hundreds of people to take the

plunge with him. The project seems insane because he isn't trying to

fulfill his inspiration -- he's trying to locate it and execute it at the same time. Yet even when his ambition grows to megalomania and his film

begins to fall apart, his zeal and riskiness are as elating as they are

dismaying. He's in the gambling tradition of American entrepreneurs -- there

isn't a single corporate-like censor in his consciousness (or apparently in

his corporation, Zoetrope).

The excitement comes from watching him go out on a limb; the

heartbreak comes from seeing him saw it off behind him. You feel you're

seeing, in extremis, the same creative force that generated the "Godfather"

films and helped shake American movies out of their 1960s doldrums.

Of course, despite his youth (now he's all of 60),

the "Godfather" films had given Coppola the stature of a patriarch. What fans

knew about his life only reinforced that image. Growing up in Queens and on

Long Island, he suffered through polio at age 9 (an episode he alluded to in

his script to "The Conversation") and grew into a high school misfit, living

in the shadow of his confident, intellectual brother August. But once Francis

started directing college theater and film he became a charismatic figure.

With his mushrooming influence in Hollywood he was soon able to employ his father, Carmine -- an ace flutist and frustrated composer -- to write scores for his

movies. And he directed his younger sister, Talia Shire, in her

indelible performance as Connie Corleone in the "Godfather" films. Coppola

was also the father of three children, Gio, Roman and Sofia; he infected

them, too, with the movie bug. (All went on to work in movies, Sofia as a

full-fledged director; Gio was killed in a speedboat accident in 1986.)

"Hearts of Darkness" lets you sample the dumbfounding emotional

arsenal that this premature sage must employ to get his way. You get to

witness the child-wizard flirtatiousness that continues to draw creative

people to Coppola. He has a knack for making himself larger rather than

smaller by revealing his insecurities. Sometimes, the audio track drips with flop-sweat. In "Hearts of Darkness," he says that he knows he's making a bad movie, that

people don't believe him because of what he's pulled off before. (By 1976,

he'd made three classics in a row: "The Godfather" in 1972 and "The

Conversation" and "The Godfather Part II," both in 1974.)

His frankness has a heroic quality. He's totally disarming when he pinpoints the biggest fear of any audacious moviemaker -- that his work won't live up to the subject

matter, that it will be merely "pretentious." He facetiously compares

"Apocalypse Now" to the disaster films of Irwin Allen ("The Towering Inferno," "The Poseidon Adventure," etc.). Are these contradictory ejaculations the mark of a driven artist, a self-conscious impresario or a man trying out alternatives? Of course, he is all three --

that's why at the time of "Apocalypse" he seemed indestructible.

A series of nonstop catastrophes wreaked havoc on the backbreaking

shoot in the Philippines. A ruinous typhoon deluged locations and wiped out

sets. The Philippines armed services were unreliable. Crucial helicopters

were often called away to fight Communist insurgents, and fresh pilots had to

be coached from scratch every day. Coppola fired one star (Harvey Keitel),

shot around the heart attack of another (Martin Sheen) and wrote (and shot)

around the forbidding obesity of a third (Marlon Brando). He encouraged his actors to be their characters: In the documentary, Sam Bottoms talks of

playing a stoned soldier while on an array of drugs himself; Frederic Forrest

-- who's terrific -- reveals just how surprised he was when Coppola sprang a

tiger on him. The 14-year-old Laurence Fishburne is an electrifying presence

off-screen as well as on. There's a glimpse of Dennis Hopper as a

decade-older, strung-out Easy Rider, with melancholy in his eyes and gray in

his beard -- perfect for the role of a freelance photographer too long away

from home. Through it all, Coppola says that the film's meanings will come

into focus partly from the experiences he has making it.

After two years of post-production, the nearly finished film

screened at Cannes in 1979 and ended up sharing the Golden Palm with "The Tin

Drum." Coppola gave a frighteningly perfervid press conference in which he

said, "My film is not a movie; it's not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam."

There must have been something both lunatic and exhilarating about Coppola at

that press conference, getting carried away with his own metaphor: "We had

access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little, we went

insane."

Of course, "Apocalypse Now" isn't Vietnam; it is only a movie (as

Sheen's wife told him in the hospital). Its reflection of the filmmaker's

despair doesn't deepen its view of the grief in Southeast Asia. John Milius'

original script and Coppola's nonstop rewrites couldn't support the

director's flood of notions; the production was designed at every stage as

the sort of spectacle that overwhelms audiences rather than prods their

understanding -- a movie that blows minds, not a movie that expands them. It

wasn't even an actors' showcase. Only the most stylized performance -- Robert

Duvall's bravura, "Patton"-esque caricature of Lt. Col. Kilgore -- had a chance

to stand up to the physical grandiosity, and understandably won the most acclaim.

Yet the movie has become a contemporary benchmark. How many

reviews of the current "Three Kings" tried to explain that film's combination

of realism and absurdity by evoking "Apocalypse Now"? The lasting message of

"Apocalypse" lies not in the thin, awkward retread of Joseph Conrad's "Heart

of Darkness," with Brando's Kurtz repeating (like his namesake in Conrad)

"The horror! The horror!" No, the message lies in its druggy yet precise,

blazing downer style, which says more about our post-Vietnam attitudes toward

war than it does about war itself.

When I talk to moviemakers about Coppola, "Apocalypse Now" comes

up as often as the first two "Godfather" films or "The Conversation." They

admire its formidable craftsmanship -- the hallucinogenic merging of sound

and image so that you can't tell electronic buzz from animal chatter, or

jungle sounds from the whoosh of helicopters. Or the way palms burn abruptly

with napalm, not with a dramatic burst but as naturally as sunflowers opening

up to daylight, while the Doors' dirge "The End" plays out against the

flames. Coppola has selected "Apocalypse Now" to spearhead his latest cutting-edge venture, American Zoetrope DVD Lab (the wide-screen, Dolby-digital transfer of "Apocalypse" hits stores Nov. 23). And "Apocalypse Now" was picked as the first subject of the Bloomsbury Movie Guide series (Karl French did the study). Reading it back-to-back with Michael Schumacher's dogged new biography, "From the Heart: The Life and

Films of Francis Ford Coppola," I found the "Apocalypse Now" guide more

engaging and illuminating.

Maybe that's because, particularly when viewed in conjunction

with "Hearts of Darkness," "Apocalypse Now" becomes a movie epic that's

really the epic about moviemaking, illustrating all the skills contemporary

filmmakers need when pursuing an original vision on a mammoth scale. Seen

that way it assumes a mad grandeur. There's Coppola's ability to talk a

great movie: When he says that he considers the river journey a trip into

past history, the concept is strong though the proof is weak. There's his

seductive visual sense -- you can see why Eleanor Coppola, in her lucid,

too-little-read "Apocalypse" diary, "Notes," compares watery landscapes lined

with fish traps to "Paul Klee drawings on blue-gray papers." There's his

consciousness of publicity and damage control, especially when he tries to

maintain stability after Sheen's heart attack. And there's his astounding capacity for leadership, not just when he's dynamic and eloquent, but when he's bewildered.

The makers of "Hearts of Darkness," Fax Bahr and George

Hickenlooper, placed Coppola in the tradition of Orson Welles, who scored a

sensation with his radio adaptation of Conrad's "Heart of Darkness," and tried

unsuccessfully to helm a movie version before moving on to "Citizen Kane."

They frame the film with Welles' Conrad broadcast, and it's a savvy stroke:

It passes Welles' mantle of ravaged Hollywood genius on to Coppola. But it was RKO

Studios, not Welles, that put the kibosh on his "Heart of Darkness," and Welles

never had the chance after "Citizen Kane" to mount his projects with

Coppola's spectacular pyrotechnics. And if Coppola hocked his own assets to

keep "Apocalypse Now" in production (as Welles poured his own money into his

later films), Coppola's distributor, United Artists, limited his liability by

acting as guarantor for his most publicized loans.

The similarities between Coppola and Welles are illuminating, particularly their

ability to galvanize troops and their experimentation with every element of

film. But so are the contrasts. Welles' "Othello" won the Golden Palm at Cannes, but hardly anyone went to see it. "Apocalypse Now" not only co-won the Golden Palm, but also grossed more than $150 million worldwide. Welles made a living in his later years as the spokesman for Paul Masson wine. Coppola has made a fortune manufacturing his own wine. Coppola's myriad extra-movie interests -- from

publishing San Francisco's City magazine in 1976 to publishing Zoetrope

All Story magazine today; from restoring the Blancaneaux Lodge in Belize to

reunifying the Niebaum and Inglenook wine estates in Napa and expanding his

Niebaum-Coppola wine and food company -- have augmented rather than diluted

his status in the movie game. He's on the board at MGM, and is said to have

his eye on the driver's seat at United Artists, now an MGM subsidiary.

During the chaos of the Philippines, Eleanor Coppola realized that

her husband might have finally found what he wanted: a community of artists.

That longing for connection with other artists and old traditions fueled

Coppola's art from the beginning. Some careers split naturally before and

after landmark movies -- Robert Altman with "Nashville," David Lean with "Lawrence of

Arabia." "Apocalypse Now" has been the dividing line between the untrammeled

accomplishments of early-

carve out an empire of art and efforts to intensify his own artistic acts.

In 1997, before the 25th anniversary celebration of "The

Godfather," Coppola told me, "I think the style of getting together with

other people, in this case young people -- a lot of it came out of my

experience in college. I was a theater major at Hofstra, a school that has a

wonderful theater and theater tradition. We were near New York so we were still

close to the professional theater geographically, and that was the time, when

I was 17 or 18, that I sort of came into my own. And on campus the theater

was in that style of student organization where we students sort of had the

power. Like many people of my age I was influenced by the films of Orson

Welles and Stanley Kubrick, and the wave of great foreign films. So I had one

foot in international film and one foot in an entrepreneurial sort of

theatrical tradition." After Coppola graduated from UCLA film school, "It was

natural for me," he said, "to try to be close to friends and people I admired, such as Carroll Ballard and John Milius and George Lucas, and with them try to launch something independent and something American that was really related to cinema. It was like doing in a second installment what I had liked doing in college."

As far back as college and film school, Coppola was willing to mix the image of an artist with that of a go-getter. Peter Bart, the journalist-turned-Paramount executive (now editor of Variety) who approached him to make "The Godfather," told me that he remembered Coppola in film school as "already a great rewrite man; I'd written a story for the

New York Times about him as an up-and-comer. I wasn't sheltered -- I had

been a writer for both the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, I

had covered the Supreme Court and the Watts riots. Yet what was astonishing

me then was that so many young filmmakers were really impressive. It was 15

years later that I realized that there was this amazing incursion of talent

into the industry -- Hal Ashby, Martin Scorsese, Lucas -- that hasn't happened

since. And Coppola was perhaps the brightest."

He was also readier than any of his peers to pay his dues, whether that meant patching together a shoestring nudie film ("Tonight for Sure," 1961) or doing odd jobs and a quickie horror flick for Roger Corman ("Dementia 13," 1963, when he married Eleanor), or signing up as a screenwriter-for-hire for Ray Stark's company, Seven Arts. Coppola's first

"personal" movie, the 1966 youth comedy "You're a Big Boy Now" (developed on

his own dime), is the work of an exuberant young showoff. What's most

entertaining is the quicksilver location shooting and editing. Along with the

Lovin' Spoonful music on the soundtrack, the film turned New York into what the

city's PR campaigns called "a summer festival."

Coppola confessed to me that he made his next film, "Finian's

Rainbow" (1968), because "musical comedy was something that I had been raised

in with my family and I thought, frankly, that my father would be impressed

if I were suddenly directing a Hollywood musical comedy -- because he had

wanted to break into that Hollywood area." Coppola portrays

"Finian's Rainbow" as a "move against my main direction of doing original

films -- a left turn" meant to pay off a psychic debt to his dad. But what

makes the film affecting is Coppola's yearning to connect with Broadway and

Hollywood's musical-comedy legacy. Enough bubbles of spontaneous lyricism

erupt to keep the creaking fantasy afloat -- especially in the opening-credits scenes of Fred Astaire and Petula Clark, as an Irish rover and his daughter, traveling through magical landscapes on their way to "Rainbow Valley, Missitucky" (Carroll Ballard shot this footage). And on this film Coppola befriended a former acquaintance, USC film school legend George Lucas, who was observing the production on a scholarship from Warner Bros.

Brainstorming with Lucas about making unconventional movies

outside Hollywood rekindled Coppola's dreams of spearheading revolutionary

theatrical enclaves. "I wanted to be with friends in a 'La Boheme'-style

fraternity," Coppola confirmed. "It's true, the stimulation you receive

from hearing what so-and-so is writing, what they're doing; the admiration I

had for these other filmmakers was self-empowering, and stimulating for my

own work. And that has been true more generally. You ask why there are

movements in movie history -- why all of a sudden there are great Japanese

films, or great Italian films, or great Australian films, or whatever. And

it's usually because there are a number of people that cross-pollinated each

other." When I mentioned Bart's feeling of being stunned that all these

"brilliant" filmmakers seemed to be swarming around him, Coppola replied, "I

don't know how brilliant we were, but we were very enthusiastic about movies

and the chance to make them."

The idea of escaping from Hollywood chores and bringing a

generation with him fueled his determination to make his next film, the

offbeat road movie "The Rain People" (1969). He plowed his own money into

mobile equipment and began shooting flashback scenes at Hofstra before he

landed financing for the movie. Working from his original script about a

pregnant Long Island housewife (Shirley Knight) who leaves her husband and

hits the highway, Coppola surrounded himself with key collaborators,

including Lucas, editor Barry Malkin (billed as Blackie Malkin), "sound

montage" expert Walter Murch and actors like Robert Duvall and the

top-credited James Caan, playing a brain-damaged college football player.

The film is simultaneously a mood piece and a period piece -- it evokes an era

when personal disintegration echoed the fraying of society at large. So three

decades later, even its arty self-importance seems expressive. More

significant, with Murch wedding aural poetry to the moody cinematography of

Bill Butler, the film showed one of the first creative trademarks of the independent company whose name would end the credit roll: American Zoetrope.

Shortly after finishing up "The Rain People," Coppola led his exodus

of tyros from Hollywood to San Francisco and established American Zoetrope

as a studio where a hundred visions could bloom. "He infused everybody with

this great indomitable spirit," John Milius told me. "He was the rebel envoy.

He hired four or five people from my class in USC, and he was our leader."

(Milius went on to direct such films as "Dillinger," "The Wind and the Lion"

and "Conan the Barbarian.")

Yet Coppola nearly lost his dream with the first American Zoetrope

production, Lucas' Orwellian fable "THX 1138" (1971). After viewing the

rough cut, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, which had sunk development money into

Zoetrope's slate, decided to oversee the final editing of the film, reject

Zoetrope's future projects and demand repayment of their seed money.

"Warner Bros. did not in any way make us a loan," Coppola told me, still

seething decades later. "They never even said it was a loan." It was Lucas,

the director of problem child "THX 1138," who pointed the way out of

dire straits and urged him to direct a big bestseller for Paramount. "It's

true, George is very practical," Coppola said. "He really wanted me to do

'The Godfather.'"

The making of "The Godfather" is now cemented in movie history as

a renegade movie victory on the scale of "Citizen Kane." Coppola used all his

theatrical and Machiavellian powers, starting with a mock epileptic fit, to

secure casting choices like Brando and Al Pacino, maintain a stately pace and

an intricate lighting scheme and preserve the Italian-opera flavor of

Nino Rota's score. The saga has been retold many times -- including once by

me (in the March 24, 1997, New Yorker). And yet what I think has gone unstressed is how Coppola worked by magnetizing others. Although "The Godfather" was a Paramount picture, not a Zoetrope film,

Coppola made a host of creative choices with his once and future Zoetrope

cohorts.

"At least a year before 'The Godfather,'" casting guru (and producer) Fred Roos recalled, "we would schmooze about various actors and exchange opinions on who was interesting coming up. I knew Talia; she may have talked to him about me. Then he called me on 'The Godfather' and asked if I wanted to work on this." One of Roos' personal coups was finding John Cazale in New York and realizing that he'd be the perfect Fredo. (Cazale

would also appear in "The Godfather Part II" and "The Conversation"; he died

in 1978.)

The late Mario Puzo told me two years ago that when he visited Coppola in San Francisco at the time "The Godfather" was being made, he was impressed with the Coppola group's "high schoolish team spirit." One of the most important members of that group was Murch, who was officially functioning as

the sound effects supervisor on "The Godfather" but was always involved in

Zoetrope projects as a top-flight film mind. (He had co-written

"THX 1138.")

"From my perspective," Murch told me, "Francis would never have

made the 'The Godfather' had the crisis not happened between him and Warner

Bros. When the studio said that the $300,000 they had fronted Zoetrope was a

loan, Francis was deeply in the hole and had no prospects for getting out

until Peter Bart made the call for 'The Godfather.' On one level, he needed the

money; there was also something about the material that deeply resonated in

him. He was even ambivalent about that until he really got into it.

Obviously, he was able to tie it into his life as a member of an Italian

family and also as someone who'd experienced the movie business as Big

Business. The fusion of the two was what was new about the film. It gave us

IBM or AT&T with a human face. Rather than seeing a corporation as thousands

of faceless people, Francis got it down to five faces, each a psychological

type, the father and four brothers.

"Aside from the fact that the role of the

Godfather was a comeback for Brando, who'd been exiled to the outhouse for

sins against the studios, it was a stroke of genius to cast four New York

actors [Pacino, Caan, Cazale and Duvall as the adopted son, Tom Hagen], who

had all become actors because Brando had inspired them," Murch continued. "Each one was trying to impress dad with some aspect of dad that he had honed himself. So there

were all these harmonic resonances of Francis and the material, and Marlon

and the material, and the actors -- the sons of the acting mafia of which Marlon Brando is the Godfather."

"Francis fell in love with the actor who played Fredo," Puzo

said, "and changing Fredo's character was Francis' doing." Coppola put

Puzo on his side early on -- a wise move, since Puzo was both his font of

Mafia lore and an astute storyteller in his own right. "On 'The Godfather

Part II,'" Puzo said, "when Francis wanted Michael to murder Fredo, I told

him not to do it. But Francis was adamant. Then I said, All right, but you

can't let Michael do it until their mother dies, and it turned out to be the

right decision -- it even added tension to the funeral scene."

To Puzo, "Francis had to do all the fighting, and I've always felt that's where all

the credit should go."

But Puzo took his own proprietary pride in their shared decisions: "I know Diane Keaton hated that role [as Michael Corleone's wife], and yet she never realized that we picked her because she had a sunny face with all those grim mugs; she represented innocence in the midst of all that corruption, even though it might not have called on all her talent.

People never talk about Keaton's role, but she's the reflection of the real

world opposite the Mafia world -- that was my intention, anyway."

The greatness of "The Godfather" emerged both from its "harmonic

resonances" and from its dissonances. Coppola didn't just go to war with Paramount

during the making of the movie; he also engaged in tooth-and-claw combat with

his celebrated cinematographer, Gordon Willis. Even though they and production

designer Dean Tavoularis had agreed on the film's tableaux style, achieving

it became an agony for Coppola and Willis. It's a measure of Coppola's

confidence and clarity at this creative peak that he rehired Willis to do

"The Godfather Part II."

Under pressure to repeat the success of the first film, Coppola

achieved an unprecedented American urban epic. What the two films said

together was that for the immigrant groups that have become this country's

backbone, the American Dream was always limited by the burdens of poverty,

unsettled Old World scores and insular cultures. As in the old countries,

immigrants were prey to powerful economic and political forces; but here

these forces took more various, insidious forms. Many post-Vietnam movies

told us that America was evil, but "The Godfather Part II" told us that in

America the evil sleeps with the good. The same Senate committee that exposes

the Corleones includes a politician in the family's pocket -- one of many

who have paved the Corleones' road to criminal ascendancy.

In between the "Godfather" films came the precious gem "The Conversation," which once

again displayed Coppola at his pinnacle -- synthesizing influences,

reconciling conflicts and shrewdly delegating responsibility until he created

a masterpiece. It was fellow filmmaker Irvin Kershner ("The Empire

Strikes Back") who nudged Coppola to check out the world of electronic

eavesdropping. Under the influence of Antonioni's "Blow Up" (and Kurosawa's

"Rashomon"), that hint grew into a tour de force of suggestive filmmaking

about a hermetic, guilt-wracked bugging master named Harry Caul (Gene

Hackman) who believes he hears intimations of murder on surveillance tapes.

Once more, Coppola found himself and his production designer (Tavoularis again) at loggerheads with a renowned cinematographer (Haskell Wexler) during filming; this time, he fired Wexler and continued with Bill Butler, the veteran of "The Rain People." More important, he entrusted the working out of the intricate audio clues (and ultimately the clinching of the plot) to Murch, who for the first time was also made supervising editor. When the film premiered, the technological tricks and sleek corporate backdrop

evoked Watergate. Thanks to Murch's uncanny instincts and Hackman's uniquely

clammy, subtle performance, the movie captures a more elusive and universal fear -- losing the power to respond, emotionally and morally, to the evidence of one's senses.

The influence of Coppola's first two "Godfather" movies and

"Apocalypse Now" has been epochal, from their catch phrases ("I'll make him

an offer he can't refuse," "I love the smell of napalm in the morning") and

divergent techniques to their expressions of contemporary confusion. But "The

Conversation" has had its own lingering aftereffects -- most notably last

year, when screenwriter David Marconi, who worked as a gofer on Coppola's

"The Outsiders," penned the sizzling high-tech thriller "Enemy of the State,"

in which Gene Hackman co-starred (with Will Smith) as a grizzled, more ornery

version of Harry Caul. With each passing decade, "The Conversation" seems

more prophetic in its demonstration that the more technology advances, the

more it leaves us feeling existentially stripped.

In the seven years between the releases of "The Godfather" and "Apocalypse Now," Coppola produced "American Graffiti," launched Carroll

Ballard's feature career with the Zoetrope production of "The Black

Stallion" and saw Lucas and many of the younger producer-director's friends

veer off into their own company, Lucasfilm. When he didn't know how

successful "Apocalypse Now" would be, he streamlined Zoetrope into a company

mostly meant to service only himself; when "Apocalypse Now" became a hit, he

tried to expand it again with the purchase of an actual physical plant (the

creaking Hollywood General Studios) in Los Angeles. "I saw him a lot then,

during the Hollywood thing," Milius told me in 1997. "It was his last great

act of rebellion. There were grand ideas, like doing 'One Hundred Years of

Solitude' or 'The Killer Angels.' He was going to get Werner Herzog $20

million to do 'The Conquest of Mexico.'"

But the ambitious studio plans didn't survive the fiasco of Coppola's

exercise in nouveau back-lot style, "One From the Heart" (1982). Milius

insists, "Like I say about the American Indian, or the mob in Vegas -- I

think he gave in too easy. But I think he just got worn out after 'Apocalypse

Now,' and it changed him forever."

The '80s and '90s saw the emergence of several new and barely

recognizable Coppolas: the nostalgist of "The Outsiders" (1983), "Peggy

Sue Got Married" (1986) and "Tucker" (1988); the overactive visual virtuoso

of "Rumblefish" (1983), "The Cotton Club" (1984) and "Bram Stoker's

Dracula" (1992); the kiddie filmmaker of "Life Without Zoe" (his segment of the 1989 trilogy "New York Stories") and "Jack" (1996). When he consented to extend his greatest triumph with "The Godfather Part III" in 1990, the result was a fascinating misfire (and a suitable subject for a running joke on the part of TV's "Godfather"-loving mobsters

in "The Sopranos": "What happened with 'III'?").

Yet every so often, passages in

a Coppola film will show signs of his old warmth and fullness, as in the

marvelous funereal rituals and the "Old Guard" camaraderie of James Caan and

James Earl Jones in "Gardens of Stone" (1987), set in Arlington National

Cemetery during Vietnam. And, in general, there's no sign that Coppola has

merely become cynical or hackneyed or malicious. I was not a fan of "John

Grisham's The Rainmaker" (a minority position when it premiered in 1997), but

the problem was that Coppola, as the writer-director, had given himself over

to Grisham too completely; he showed flair with the extensive supporting cast

of slickers and slimeballs (particularly Danny De Vito's self-described

"para-lawyer"), yet was paralyzed into sentimentality by Grisham's bright-eyed

legal-beagle hero (Matt Damon).

I interviewed Coppola about "The Godfather" when he was working

on "The Rainmaker." He mentioned that a tool from his theater background

that he used consistently in movies was a notebook like the one Elia Kazan

put together while directing "A Streetcar Named Desire," in which he

"provided the core to every scene. When I did 'The Godfather,' I took a lot

of time and annotated the novel very carefully, trying to extract absolutely

everything that I thought pertained, and put it in the form of a big

loose-leaf book. I made a synopsis of each section and described the time,

the period, the era, and outlined the pitfalls. And then I actually directed

from that book. I find when I do a novel, I don't really use the script, I

use the book; when I did 'Apocalypse Now,' I used 'Heart of Darkness.' I find

that novels usually have so much rich material it's better to look through it

and base the film on that."

Although Coppola has always declared his desire to make original

movies, the fact remains that most of his major work has derived from

fiction; even Harry Caul's character in "The Conversation" was rooted in

Hermann Hesse's "Steppenwolf." Viewed in that light, the fluctuations in his

directing career are rooted in the varying quality of his sources, from Puzo

to Grisham. Just like his magazine Zoetrope All Story, which "purchases both first

serial rights and film options on the short stories and one-act plays

published here-in," Coppola's ongoing effort to gain control of studios and

production companies, with UA as a possible next goal, may derive from an

ambition to acquire massive and diverse amounts of material the way Old

Hollywood did.

Coppola is only 60. He may also want to reestablish the communal

dream he banked so much on achieving and never fully abandoned. Were he able

to assemble a millennial team as strong-minded and challenging as his old

one, who knows what wonders he could still pull off. "Geronimo, Sitting Bull

-- a lot of those great Indians went off the reservation in one great spark

of rebellion," Milius told me two years ago. "Francis may have that kind of

gesture and vision left in him; and if he ever really wants to do it he can

count on my sword, too."

Shares