Clint Eastwood's "Letters From Iwo Jima" springs from an admirable impulse: This companion piece to Eastwood's flawed yet complex "Flags of Our Fathers" sets out to tell the story of the Battle of Iwo Jima from the viewpoint of the Japanese soldiers who fought and died there. Eastwood, working from a script by Iris Yamashita (the story is by Yamashita and Paul Haggis), hopes to humanize these soldiers, showing them as inexperienced young men who loved their families, who were under orders from their superiors to fight viciously, and who were victims of a culture in which dying honorably was considered far more important than preserving life.

The impulse is commendable; the movie isn't. More than 6,000 American soldiers were killed during the 36-day battle; the number of Japanese troops killed was 21,000, which included most of the soldiers defending the island. The Japanese were notoriously vicious fighters. (Firsthand accounts from servicemen who fought in the Pacific arena, like William Manchester's memoir "Goodbye, Darkness," are numerous and remarkably consistent. And the idea of the Japanese as ruthless warriors isn't just a Western prejudice, as the Chinese who survived the Rape of Nanking would tell you.) There's no doubt that Americans at the time of World War II, including civilians, found it all too easy to caricature the Japanese as the "other." Even Bugs Bunny cartoons portrayed the Japanese as something other than human. As Paul Fussell wrote in his essay "Thank God for the Atom Bomb," "Among Americans it was widely held that the Japanese were really subhuman, little yellow beasts, and popular imagery depicted them as lice, rats, bats, vipers, dogs, and monkeys." He goes on to note that "some of the marines landing on Iwo Jima had 'Rodent Exterminator' written on their helmet covers." You could see characterizations like that in movies made during the war, like the 1943 "Bataan."

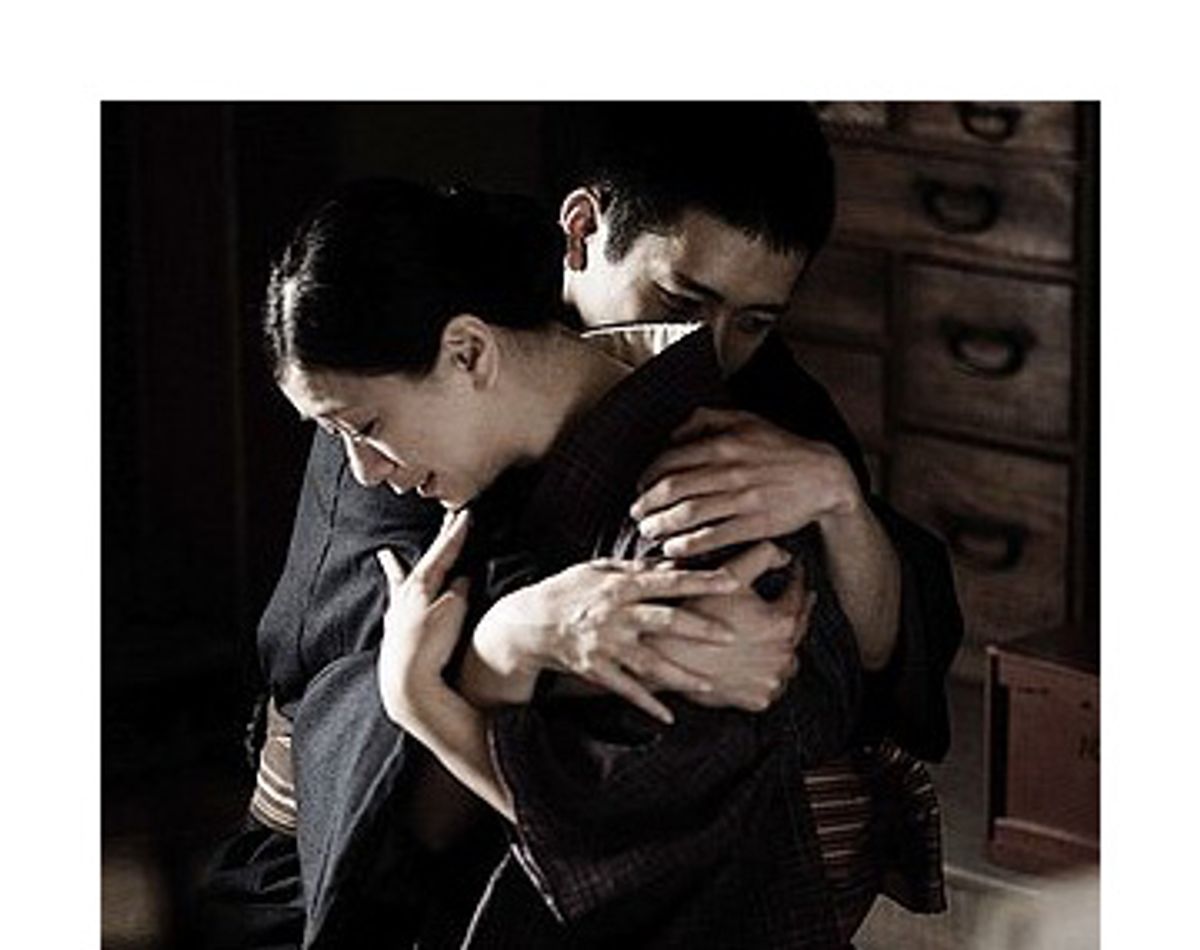

So it's easy to understand why Eastwood would want to make a movie like "Letters From Iwo Jima" -- its dialogue is in Japanese, with English subtitles -- which focuses on the experience of several young Japanese soldiers, chief among them Saigo (Kazunari Ninomiya), and their relationship with their superiors. "Letters From Iwo Jima" shows us these young, untested men -- the Japanese counterparts of the touchingly green youngsters Eastwood shows us in "Flags of Our Fathers" -- being ordered to dig miles' worth of tunnels on the island. They face starvation, exhaustion and disease. And they're trained to fight ruthlessly for the honor of their nation -- and to kill themselves rather than face defeat. One sequence in particular gives a good sense of the cultural attitudes that have been ingrained in these young men: In a flashback, we see Saigo answering a knock at the door and learning that he's been called up to serve, which means he'll have to leave his young, pregnant wife. Neighbors flutter around the couple, congratulating Saigo for having received the privilege of being asked to fight, oblivious to the dismay and apprehension on their faces.

Eastwood's sympathy doesn't stop with the young soldiers: He shows Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi (played by Ken Watanabe, a wonderful actor who's far too limited by the roles he's usually given), who led the Japanese defense and was greatly respected by American generals as well as his own men, making little sketches, based on happier times, to send home to his son. (In real life Kuribayashi's drawings survived, almost miraculously, and have been collected in a book, "Picture Letters From Commander in Chief," which is one of the sources for Eastwood's movie.)

But Eastwood is so busy humanizing Japanese soldiers that he ends up rewriting history. Early in the movie, before the battle has begun, we see the Olympic champion show-jumper Baron Nishi (Tsuyoshi Ihara) arrive on the island with his horse; when the fighting starts, he's going to lead the men, on horseback, in the charge. The sequence is intelligent, and somewhat touching, for the way it suggests an ancient, civilized (as much as war can ever be civilized) approach to battle. But in a very brief later scene, we see another officer showing his men the red cross displayed on the bags of American medics, urging them to kill these men whenever possible.

This is one of the few instances in the movie where Eastwood faces up to the more vicious tactics of Japanese soldiers: Mostly, we see young Japanese men fearing for their lives, coming close to starvation and knowing they're fighting a losing battle. They clutch pictures of their families and loved ones, a convention that's been used in war movies for years, sometimes badly and sometimes well, to underscore the humanity and innocence of American soldiers. Of course, Japanese soldiers felt those things, too. It's terrible when a soldier, any soldier, has to leave his children. But using a person's ability to procreate as a way of making the case for his or her basic human decency will only take you so far. (In 50 years are we going to be seeing movies like "Lynndie England: Misunderstood Mommy"?)

Near the very end of the picture, some American soldiers encounter a corpse, and the commanding officer warns them that it may be booby-trapped. It's the first mention of booby-trapped corpses in the movie, an afterthought that's never explained, as if Eastwood were hoping to slip it in without our noticing -- as if he'd hoped we wouldn't leave the movie wondering which one of these fresh-faced young Japanese kids might have booby-trapped a dead body.

Eastwood knows, as we all do, there were atrocities committed on both sides, not just at Iwo Jima but throughout the war. (I shiver every time I see, in Paul Fussell's "Thank God for the Atom Bomb and Other Essays," a '40s-era Life magazine photo of a nicely dressed American blond contemplating the human skull before her on her desk -- the skull of a Japanese soldier, sent to her by her GI sweetheart.) But Eastwood can't bring himself to deal with any genuine complexity here. He wants to make the case that in wartime, people who are essentially good can do horrible things. But downplaying the horror of atrocity has the unintentional effect of making it seem almost reasonable, a way of saying, "See? People sometimes have a reason for doing very bad things." It's a reduction that absolves humans of responsibility rather than challenging them to accept it.

The bitter truth is that "Flags of Our Fathers" -- a picture in which Eastwood actually gives some thought to the way we consider the young men (and now women) who fight our wars to be disposable -- made barely a blip on our movie-awareness radar when it was released last fall. (The movies were filmed back-to-back, partly on location on Iwo Jima, although they have completely separate casts.) But "Letters From Iwo Jima," a far more forced, unshaped picture, has already received far more attention, and just a few weeks back, the Hobbits at the National Board of Review sent a scroll from Middle-earth decreeing it their movie of the year. The suggestion seems to be that, at last, we're ready to accept our former enemy as human. They deserve a better -- and a tougher -- movie than this one.

This story has been corrected since it was originally published.

Shares