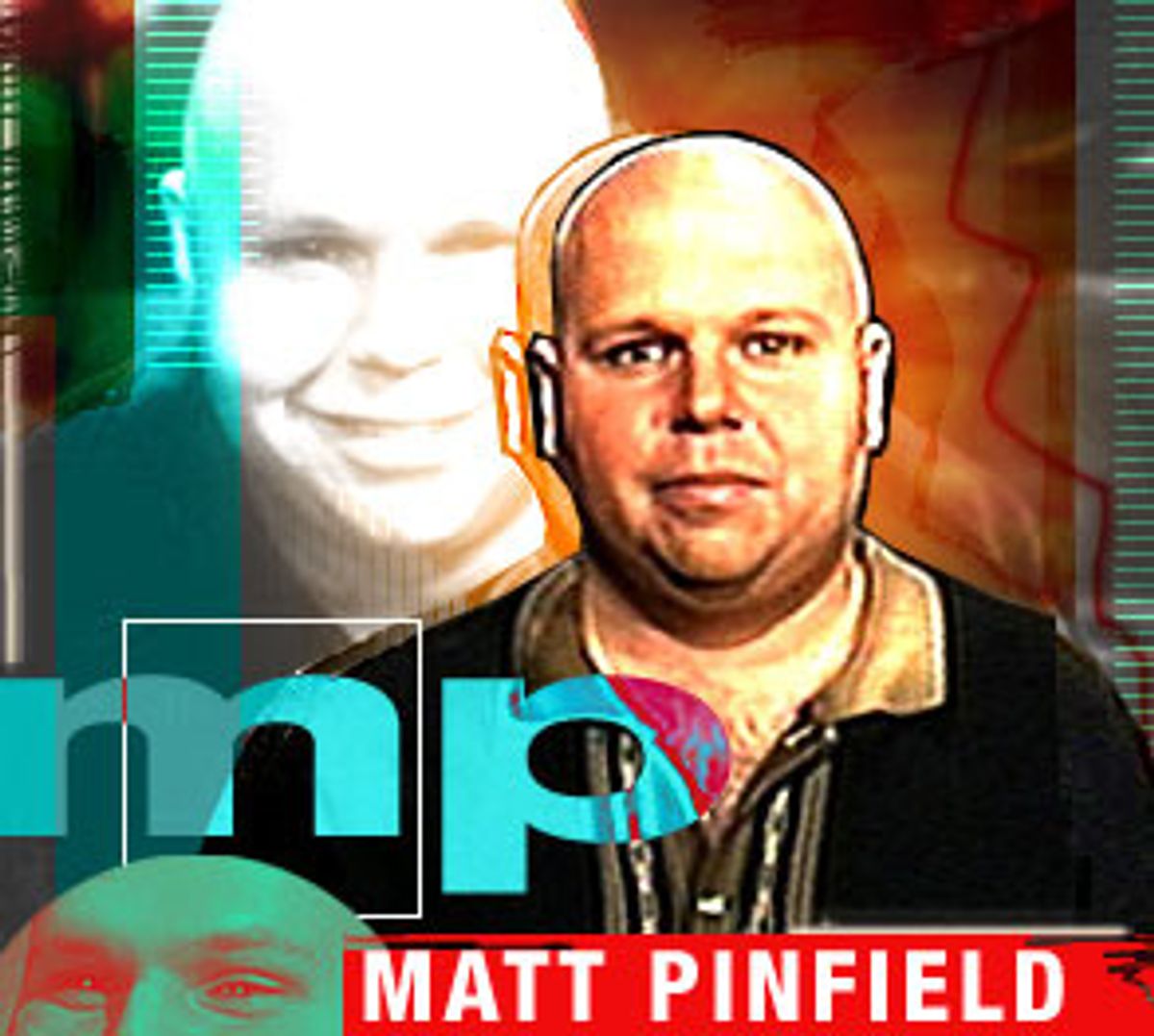

Matt Pinfield, the stocky, bald-headed broadcaster who established his reputation as the station's tough-looking savant and host of MTV's "120 Minutes" show, is starting to seem a lot more like one of those infomercial blowhards. Take a look at his new show, "Jimmy and Doug's Farmclub.com." He used to be gruff and monotone; now he's chipper and overflowing with niceness, his voice a couple of octaves higher. The guy is easy like Sunday morning when interviewing bands, tossing up softballs like "It's cool that you guys are back on the road/in the studio again" for Gwen Stefani or Dr. Dre to hit out of the infield.

Pinfield left MTV last year to join "Jimmy and Doug's Farmclub.com" when it debuted earlier this year. The show is an hour-long music television show cablecast on the USA Network every Friday and Saturday night. It showcases videos and live performances by national talent and aspiring unsigned or indie label superstars, from Beck and Nelly to the Texas band ... And You Will Know Us By the Trail of Dead.

The show looks and sounds good -- sort of like MTV when it still played music. But MTV in its 1980s prime, for all of its faults, was essentially an independent media outlet. As such, it chose the videos it would run and often angered the major labels that it depended on for music and videos. Early on, Columbia is said to have browbeat MTV into playing Michael Jackson. The roles reversed once the station had more power. At one point, the biggest record labels were so irritated with MTV -- especially because they had to give the station their videos for free -- that they even considered boycotting the music channel. Yet MTV was too strong, and the labels could never agree to work together. Sure, MTV has sucked up to the biggest stars countless times since its inception, but it has remained essentially independent of them.

That's hardly the case with "Jimmy and Doug's Farmclub.com." Hosts Pinfield and pinup Ali Landry provide the first clue that something is amiss. Both refer to the company's Web site and record label (Jimmy and Doug's Farmclub.com) more often than infomercial maven Ron Popeil employs the term "rotisserie," and Pinfield has transformed from the cerebral band geek from MTV into a kinder, gentler and dumber Mad Matt -- a glorified pitchman for "Farmclub.com," its record label and its Web site.

But there's another problem with the show that runs a bit deeper than all of Pinfield's cross-promotional pitches. At its core, "Farmclub.com" is simply an extended commercial for the biggest record label in the world, presented under the guise of wholesomely unwholesome pop-culture entertainment. For starters, the show is a block of paid programming, like an infomercial, which means that "Jimmy and Doug's Farmclub.com" buys airtime from USA outright, and then sells the commercial time itself.

Now here's where it gets good. Guess who's collecting that money? It's the USA cable channel, which is 43 percent owned by Seagram Company Ltd., which also owns Universal Music Group and "Jimmy and Doug's Farmclub.com." Of course, it's not like anyone at Universal or Seagram is trying to bury their involvement with the show, which is, after all, named after "Jimmy" Iovine, co-chair of Universal's Interscope label, and "Doug" Morris, CEO of Universal Music.

Every week, "Farmclub.com" hosts performances by three or four bands. And guess which artists are given major play on the show? Universal artists, of course: Nearly every week, since the first show on Jan. 31, at least one of the performers has been affiliated with Universal. That's airtime for more than 20 Universal artists (and for the members of Staind, who while not being connected with Universal directly, are friendly with Fred Durst, vice president at Interscope and lead singer of Interscope recording artists Limp Bizkit).

In return for providing some cool content, some performances and interviews, Seagram (via its record labels) receives a few enviable benefits. First, the conglomerate gets the opportunity to build an alliance with consumers, making them feel as if they are part of a faceless industry. Surfers can log on to the Farmclub.com Web site, listen to audio files by unsigned acts and cast votes for which artists will appear on upcoming programs. The band-o'-the-week winner gets a visit from Pinfield, shiny-happy mug and cameras in tow. The procedure manages to make Seagram look like it actually cares about been-nowhere garage bands. Meanwhile, the Universal A&R team gets a ready-made test market.

Take, for example, Tampa Bay DJ Sonique. Her song "It Feels So Good" first appeared on the Farmclub Web site. By receiving votes from Web surfers, she won a spot on the show. After the performance, the Farmclub.com label made Sonique's "Hear My Cry" its debut album. In March, Sonique landed in the Top 10 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock chart; then she jumped up to No. 85 on the Top 200, selling 20,000 records a week, and eventually went gold. Four other acts have also been signed to the Farmclub.com label, and are receiving big PR pushes and distribution help from Universal. No other media outlet has offered so many little-known bands such major airtime.

Universal also gets two hours' worth of primo advertising space for its already signed artists. According to the Nielsen ratings, the show earns about 1 million viewers per episode. Of course a large portion of those numbers came as a direct feed from the prior hour of television, USA's well-viewed WWF wrestling. It's too early to see what will happen since the show switched to Fridays, but it doesn't exactly matter: The show, ratings be blessed/damned, has reserved time slots and will continue running until April 2001. (Vivendi, which is acquiring Seagram, has mentioned separating music and liquor, but it's hard to tell how that would affect "Farmclub.com.")

The only thing stopping Farmclub.com from being a beginning-to-end commercial for Universal acts is credibility. "Universal is the source of our funding," says Farmclub.com president and COO Andy Schuon. "We don't try to hide it, we're not ashamed of it and Universal has the largest market share, so naturally, you're gonna see Universal bands. [But] for us, credibility is important. We need to establish relationships with every label. We have to operate independently. You can't have credibility that way."

It's hard to take Schon's point seriously if you believe that there is a difference between advertising and media exposure. Advertising, of course, is a marketing tool that anyone or any band with access to a small business loan or a wealthy financier's checkbook can use. Media exposure (e.g., entertainment programming), by contrast, is ideally a phenomenon of selectivity. Producers and editors at media outlets such as "SNL," MTV and even the "Today" show rely on their personal tastes (and, sure, focus groups) to invite the bands with appeal and talent to their stages. Acts that have little more going for them than friends in high places don't see a lot of exposure. Every time "Farmclub.com" features a Universal artist, it's essentially cutting out the middleman.

As entertainment, "Farmclub.com" is damn near enjoyable. The show is relatively easy on the ears (until the gas-bag performer -- and Universal-affiliated -- Enrique Iglesias starts moaning, as he did recently) and eyes, with curvy bimbos strategically placed in front of the stage and Pinfield's co-host Landry never far from the camera. You could say that it's what cable shows could become if programmers had any vision, or at least as much vision as Seagram's marketing chiefs. But when "Farmclub.com" turns out to be just another version of a bigwig corporation trying to shove product down our throats, it makes watching the show a lot more difficult. Pinfield and all of those Universal-related artists (Et tu, U2?) start to look like a mutant fish-baby: You might not know what the hell you're looking at, but you know it's not right.

Shares