For the past few years, the music industry has been on a quest for something that sounds vaguely like a feminine hygiene product -- something it hopes it found this summer: Feminem. That's as in "female Eminem." As in a miniskirted version of the bleached-blond, hot-tongued rapper who delved deep into the hearts and pockets of America, making hip-hop fans of suburban teens and baby boomers alike.

It seemed a natural progression. First, Col. Tom Parker found Elvis, a Mississippi white boy who belted out rhythm 'n' blues with enough sneer and swagger to make ladies swoon. Then über-producer Dr. Dre found Eminem, a Detroit white boy who spits rhymes with enough skill and surliness to make critics swoon. The pop industry's next idea for a Great White Hope is tantalizing: a white girl, from anywhere in America, who could serve up hip-hop with enough feminist posturing to excite teenage girls and enough cleavage to excite their boyfriends.

Candidates were rounded up. First was Princess Superstar, a Jewish-Italian diva with X-rated rhymes who released an indie album in 1995 but made her way, several years ago, into Rolling Stone. Blond as she was, the princess proved too raw -- and, no doubt, too zaftig -- to be a pop powerhouse. Then there was Northern State, a trio of Long Island femmes more Beastie Boys than Vanilla Ice. Their highbrow lyrical lines -- what rhymes with "Chekhov"? -- earned them critical nods and a hipster fan base, but alas, no Eminem-like explosion seems in store for these liberal-arts poster children (though they did sign, earlier this year, with Columbia).

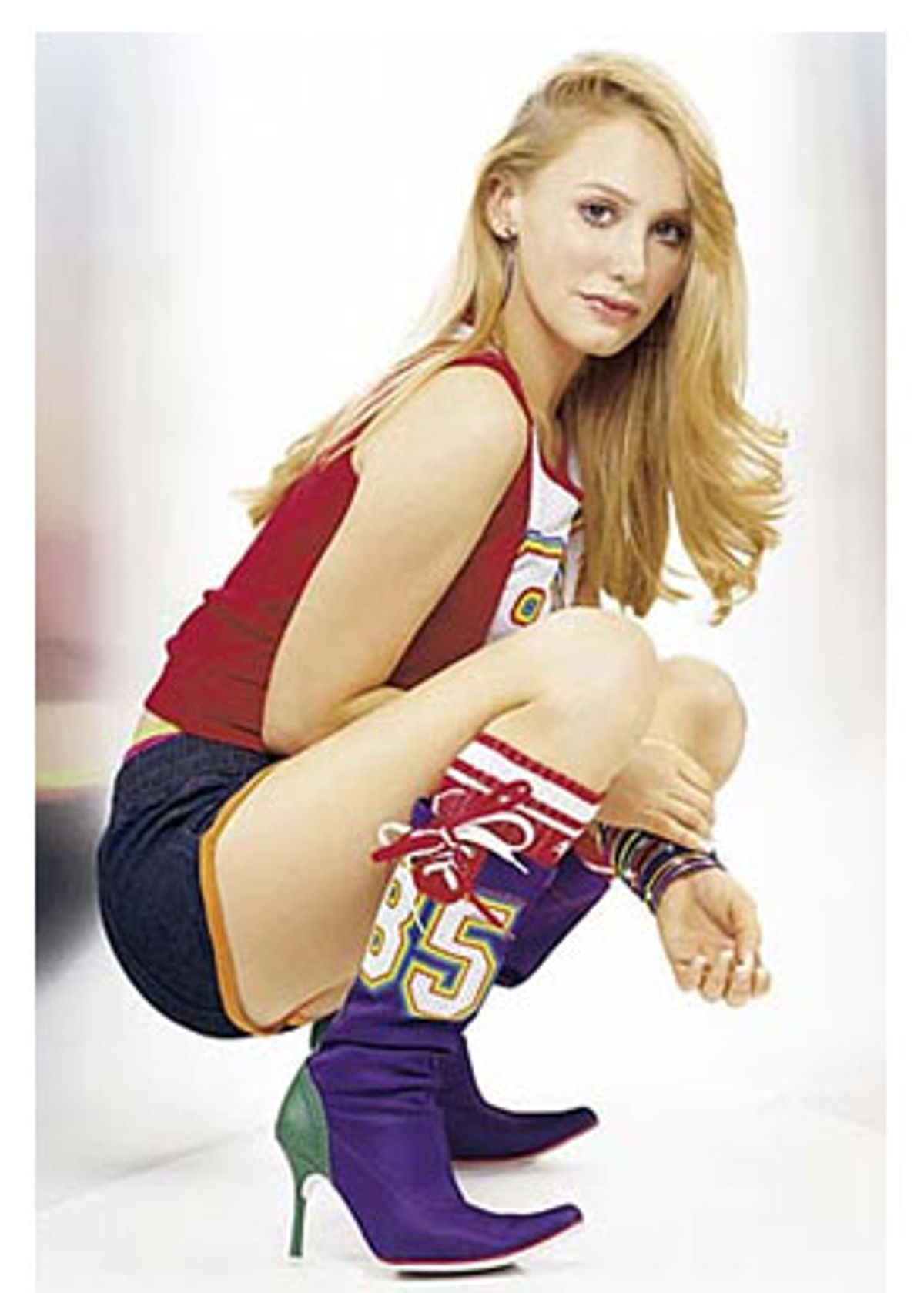

But now, courtesy of Epic Records, comes Sarai. Straight outta Kingston (Kingston, N.Y., that is, a middle-size town on the Hudson River). If the name -- a bit too conservative, a bit too biblical -- seems an ill fit for a rapper, feast your eyes on Sarai herself. She's Britney Spears meets, well, just Britney Spears.

Once word leaked that a major label had signed a 20-year-old strawberry blonde as its hottest new rapper, the magic word "Feminem" began to be whispered in industry camps and music mags. With decent reviews in Rolling Stone and a full-page spread in the New York Post, Sarai indeed seemed Eminem-esque enough. Raised, like Slim Shady, by a relatively downtrodden single mother, she dabbled in lyricism and was discovered by small-name hip-hop producers at an Atlanta gas station. She soon found her way into the beats of Scott Storch, founding member of rap ensemble the Roots and producer for, among others, Christina Aguilera and Eminem himself. Storch told CNN.com that the first time he heard Sarai, he heard "something different." She was "sort of hip-hop with a white female, and actually bringing it off like a real sister."

A real sister. The word alone is enough to make a blue-eyed soul diva quiver with pride. It's the compliment of all compliments, the stamp of authenticity for white artists venturing into so-called nonwhite musical domain. It's long been bestowed on men who could claim "soul," from Elvis to Justin Timberlake. But female crossover artists have their legacy, too. Think Sophie Tucker, a 1920s Broadway Yiddishe mama (sort of a female counterpart to Al Jolson) whom many, sight unseen, took for black. Think Janis Joplin. Think Rick James' protégé, Teena Marie, deemed the "honorary soul sister" of the '80s by Vibe magazine, or '70s singer Laura Nyro, about whom Patti LaBelle said, rehashing what's now a cliché, "She is a black woman in a white girl's body." More recently, think Nikka Costa, whose critically acclaimed album and its Aretha-esque single "Like a Feather" inspired one magazine to label her "some unholy amalgam of Janis Joplin and Teena Marie" (in other words, an honorary honorary soul sister).

Historically speaking, then, though more male white artists have built careers on the claim that their supposedly soulless pigment belied a soulful soul, there's been a fair share (no pun intended) of female ones who've done the same. For every Eminem, there's a Feminem. Right?

Not quite. The problem with this theory is, 1) Sarai is no Feminem, and 2) there will most likely never be one. That's because our current notions about men and women and crossover don't really allow for a white woman who's as "authentically" hip-hop as Eminem proved himself to be -- as authentically hip-hop, really, as the cultural guardians of all that is "true" hip-hop require him to be.

Let's start with Sarai. Her album is titled "The Original," and rightly so; it takes a real original to make hip-hop sound this bad. There's an irritating reading of hip-hop -- a remnant of the days when highbrow critics muttered things like "rap is crap" -- in which the entire genre is dismissed as mere talking and beats. It's an absurdly unfair claim, but Sarai is fodder for it. She has none of what's known in rap as flow: vocal cadence that makes speech musical without turning it to song.

For most of the album -- the this-is-me-and-here-I-am track "I Know," the female empowerment jam "Ladies," the potential single "Pack Ya Bags" -- Sarai is content to talk her way through decent beats, garnish them with a "yo" or two, and top off with a sing-song chorus. It's easy to pull a race card and call Sarai's album musical affirmative action; it's even easier to dismiss her as yet another novelty-as-selling-point act. But there's no need to do either; the sheer staleness of Sarai's music speaks for itself.

Yes, "The Original" bears the occasional tolerable track. On "Swear," featuring small-name rapper Beau Dozier, Sarai manages to sound a tad like bold, buxom rapper Foxy Brown. "L.I.F.E" has a haunting chorus sung by underrated soul singer Jaguar (annoyingly, though, we never learn the meaning of the acronym). And "Ladies" is a true waste of a hot beat, fueled by a bouncing horns section. But while the genius of Eminem -- and of countless other rappers, male and female -- lies in their verbal dexterity, Sarai makes you wish she hadn't included lyrics in her album sleeve. Here, for instance, is the lyrical gem that kicks off "The Original": "I'm about to shock the world/ bring it to ya now/ jaws drop when you see this girl/ Big like whoa gotcha shook like I ain't know."

Whoa, indeed. Sarai's lyrics boil down to four declarations. 1) I'm such a good rapper. 2) I shake my booty and you should too. 3) I've seen pain, thanks to bad men and bad 'hoods. And 4) This one's the kicker -- I am all of the above despite being white.

Call it the Eminem strategy: Reference your own whiteness before critics do it for you. Reference it enough to render it benign. Remember the line that ushered Eminem into the world, the first line off one of his first big hits? "Y'all act like you've never seen a white person before," he rhymed, sometime around the time he performed the song "White America" on the 2002 MTV Awards.

On and off record, Eminem had to address his whiteness. He had to produce a license to blackness, so to speak, and this meant sporting "white trash" like some badge of pride that substitutes class for race. It's a delightful paradox, this white trash routine: Em, along with fellow white crossover acts Kid Rock and Bubba Sparxxx, imply that they're so poor and so white they might as well be black.

Eminem (and, less so, the others) had to prove their "right" to tread on what's been deemed nonwhite musical ground because a hostile public -- its memory seared by the complex, vexed legacy of white appropriations of African-American musical forms -- required them to. If Eminem won't stop talking and rhyming about the 8 miles of his tough upbringing, it's partly because a public that associates "authentic" rap with "black" and "ghetto" won't let him. Uttered softly at first, anti-Eminem rhetoric (none-too-flattering comparisons to grand poseur Vanilla Ice, simplistic parallels with Elvis) was soon brashly overstated by hip-hop's Bible, the Source magazine, which called him "part of a dangerous, corruptive cycle that promotes the blatant theft of a culture from the community that created it."

But here's where the Sarai-Eminem parallel really falls apart. Yes, Sarai's songs offer a nod to the troubles she's seen in "Kingston upstate New York/ Lil' place up North where the style is raw" (population: 77 percent white; median income: $31,594). Yes, her hip-hop schmaltz tracks, "Mary Anne" and "It's Not a Fairytale," unleash TV movie- style sagas of teen pregnancy.

But unlike Eminem's, Sarai's persona is not built on being ultra-"real", hyperhard or hip-hop to the bone; and she's therefore unlikely to suffer the excoriation that Eminem did. "I'm a straight MTV baby," she admits on her Web site, adding that she "didn't start to fully experience hip-hop until the era of Biggie, Tupac, Nas and Jay-Z" (for the laymen, that's the early '90s and thus pretty late in the game).

Sarai doesn't, as CNN.com put it, "pepper her talk with street slang" or assert that she's a tried-and-true child of rap culture. She doesn't look the part, either: Her blond tresses are no pseudo-Afro, and her publicity shots find her bereft of bling-bling. Sarai isn't posturing herself as hip-hop's authentic white incarnation, nor, unlike Eminem, is she being criticized for doing so.

She's not alone in this. Unlike white men, white women crossing race-inflected musical boundaries nowadays are generally excused when it comes to proving street cred. When a white girl with plenty of attitude called herself Pink and delivered an album of straight-up R&B (sample lyric: "I don't want no man with the bling-bling"), few suggested she wasn't "real" enough for the genre, or that she was engaged in cultural theft. When Christina Aguilera decided to go Latin for a quick minute, learning Spanish and recording "Mi Refleja," she didn't have to produce some sort of Boricua pass; when she teamed up with rappers Li'l Kim or Redman and recorded hip-hop tracks, she didn't have to prove she was "down" enough to do that, either.

These crossover white women pull off the near impossible: They're musical chameleons, crossing generic boundaries in a way that makes them -- gasp! -- difficult to classify. Back in 1990, N.W.A. rapper Eazy-E unleashed a white protégé named Tairrie B., who was deemed the Madonna of rap; in the blink of an eye, she turned to heavy-metal goddess. Princess Superstar is now part hip-hop, part dance-raver; Northern State are femme punk with a dash of hip-hop. Pink morphed from R&B diva to punk-rock skate chick, collaborating with hardcore outfit Rancid and sharing venues with rock act Linkin Park.

On her latest album, Beautiful, Aguilera alternately displays the crooning of an alterna-chick ("Beautiful"), the prowess of a punk rocker ("Fighter," with guitar by Dave Navarro) and the tough sneer of a hip-hop diva, complete with booty shaking, rap-star collaborations and such ("Dirrty"). "I got a chance to show off all those colors and textures of my love of music and of my vocal range," X-Tina gushed to MTV.

For an album, then, or even a track (Blondie's Debbie Harry, No Doubt's Gwen Stefani and Sonic Youth's Kim Gordon have all dabbled in rap) white women are permitted to feature hip-hop; men, on the other hand, are expected to live it. For white women, hip-hop can be a style; for white men, it must be a lifestyle.

To some extent, this is a case of gender trumping genre and race: Women of any sort have a hard time transcending sex-toy status, convincing the world that their musical skill is more than some fashion or style they slip in and out of for pop America's viewing pleasure. It's hard to imagine even a black female rapper being marketed as, say, the female 50 Cent, sporting a nine-bullet halo and declaring herself harder than an algebra equation. A woman -- especially a black woman -- who is that "real" is also far too emasculating to please any male audience: black, white or other.

But the truth is, on a smaller scale and via a different set of rules, even black women rappers-cum-sex symbols like Trina, Da Brat or Eve are expected to hold it down for the streets, to maintain "hard" personas and gritty "realness." Those like Missy Elliott and Lauryn Hill, for instance, who have eluded such expectations and proved genre-defying (and, in the process, enormously creative), seem the exception, not the rule.

Authenticity, hardness, street supremacy: This is masculinity's trinity, yet to a lesser extent, it's also a standard for black women in the rap game. But white women? They're especially unlikely to get away with being so utterly unsoft, which means they'll never quite embody hip-hop the way their male counterparts do.

And that's why "Feminem," alas, is a pipe dream. Musically speaking, women have been too chameleon-like to embody "authentic" rap music, to represent it in the way the real Slim Shady does. No one expects them to, which is most likely why Sarai's background isn't scrutinized the way Eminem's or even Vanilla Ice's was -- and why hardly anyone's going to raise a fuss about some white female rapper stealing from black music and black culture.

Sarai (and others like her) are likely to merit a condescending smile and a pat on the head instead of a high-profile protest. There can be no Feminem because tomorrow Feminem might wake up and be Metallica or John Mayer. And hardly anybody would feel surprised, upset or betrayed by the transformation.

In the case of Sarai, I'm actually gunning for such an evolution, because it might produce something more tolerable than what's there now. I'm hoping it happens before a Sarai single finds itself in heavy radio rotation. Especially if that single is "Black and White," a song that embodies the only inherently offensive trend in white rap. "More than you see, more than skin and bones/ more than blood more than flesh I'm soul/ Yeah it gets rough being the minority's tough," rhymes Sarai, lamenting because her race makes "me and my roommate stand out in the complex" and thereby indulging in what can only be described as a white victim complex.

Spare us, Sarai. The only thing more tiresome than persistent reference to whiteness is persistent hallucination about whiteness as liability. Take your cue from the blue-eyed soul acts that came before you and use this so-called liability to your advantage. No one expects you to be the real deal. So make like Pink or Christina and evolve.

Shares