Seven years ago a demo by Rufus Wainwright found its way into the hands of Van Dyke Parks, a legendary eccentric best known for his collaboration with the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson, and for orchestrating songs for Randy Newman, Frank Sinatra and others. The music could not have found a more receptive listener: The songs, the voice and indeed the whole aesthetic harked back to the kind of baroquely orchestrated pop that Parks is famous for. Almost immediately he had secured Wainwright, then 20 years old, a contract with DreamWorks Records. (As Wainwright put it, "Wham, bam, thank you, Van.")

If the story sounds a little too good to be true, it probably is. What I'm leaving out is that Rufus started with two famous, well-connected musician parents, Loudon Wainwright III and Kate McGarrigle, and that it was his father who got Parks the demo. The senior Wainwright acted as the melancholy humorist of the 1960s folk revival and continues to turn out excellent albums, as well as making occasional reputation-reducing appearances on sitcoms. Kate and her sister Anna have built up a cult following performing as the McGarrigle Sisters, making elegant folk music with an almost Victorian sensibility. Their creepy, breathy harmony vocals can be heard, for example, on Nick Cave's 2001 album "And No More Shall We Part." Kate and Loudon's marriage also produced the phenomenally talented Martha Wainwright, whose continued obscurity contradicts any earlier implication of music industry nepotism.

Released in 1998, "Rufus Wainwright" was an instant hit among critics, hipsters and countless enamored high school girls who willfully ignored what Wainwright was taking no pains to hide: his homosexuality. The music was defiantly not of its time, a decadent statement of capital-R Romanticism, combining orchestrated big-band pop and Tin Pan Alley songcraft via 19th century Italian opera. What made it work so beautifully was the absence of self-consciousness, the total lack of irony. Wainwright aimed for, and achieved, a kind of Byronic grandiosity, without lapsing into Liberace-esque camp. He sang in an unabashedly full-throated voice, a brash, declamatory tenor, with the cutting power of a double reed. Two albums later, much of the harshness is gone, the oboe replaced by a deeply resonant viola. It remains one of the most distinctive voices in the pop world.

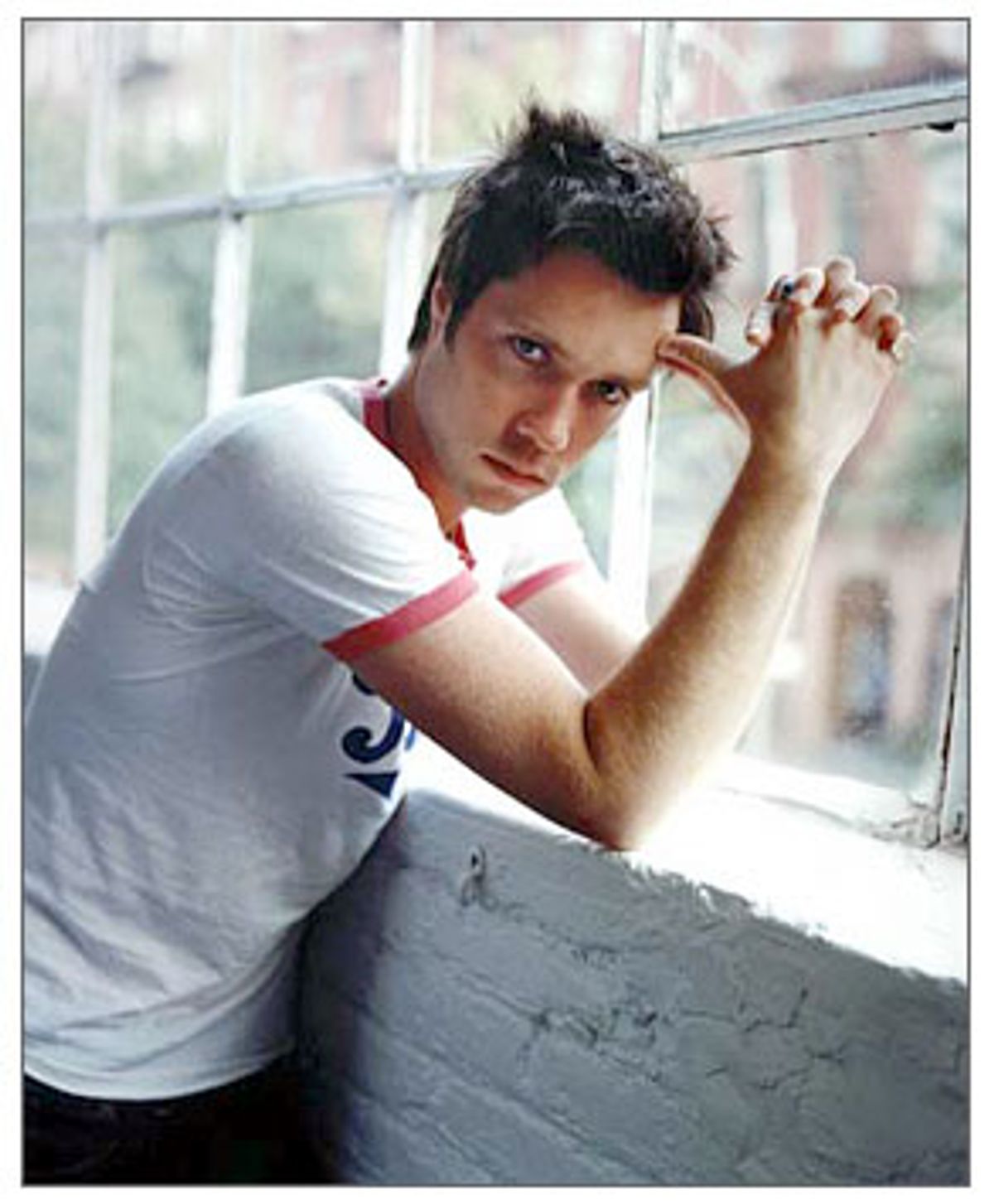

Wainwright's new album, "Want One," will be followed next spring by "Want Two." Much of the publicity surrounding the record has focused on Wainwright's now-public history of promiscuity and drug abuse. So when he sat down with me for an interview in a cafe in New York's East Village, we both wanted to talk about his music.

What's your touring band going to be for this album?

Ideally I'd like to have, I don't know, the New York Philharmonic. But I really don't know yet. I'll have to see how sales go.

If it weren't for the expense, you'd tour with an orchestra?

Well, not a huge orchestra. But, you know, I saw a David Byrne show once where he had a good little string section. I wouldn't mind that. I'd love to tour with a horn section, just for the sheer fun of it.

Would you consider trying to book a tour in classical venues?

Well, I have a dream. I have a dream! That one day I'd like to do a tour of opera houses.

Björk did that on the tour for "Vespertine." Nothing but opera houses.

All opera houses? That bitch. Sometimes I feel like Björk is the Road Runner and I'm Wile E. Coyote or something. She's just impossible to surpass. Her individual style, and really holding to her guns, and everything being so seamless in terms of the music and the visuals and everything else. She's really an amazing force.

One of the things that's very striking about your songwriting is how little folk influence there is, which is particularly strange given who your parents are. Was this a rebellion against your parents, or have you just never had a taste for folk music?

I think that all songwriting and all music is basically influenced by folk, and when I say "folk," I mean Tuvan throat singers as well. I definitely did grow up in a household awash with banjo licks and Appalachian fiddles and stuff, which in the future would be a sound that I'd love to relax into. The thing that's great about folk music is that it should be easy, easy-breezy. But definitely, my rebellion was to get into opera, and to feign the idea of being a great composer or something. So it was a type of rebellion.

Have your parents influenced you, even though you sound so little like them?

Elements of their music have severely influenced me. My mother has always had in her songwriting and in her approach a distinctly dramatic feel, and a real 19th century sensibility. With my father, it's really his writing that I'm influenced by, with his sense of humor, and the way that his lyrics are really airtight and effective.

Are there piano writers in the pop world who have influenced your music?

Well, the great ones are like John Cale and ... ummm ... John Cale and John Cale. I would say Nina Simone, but she didn't really write her songs. She was more a great arranger. Maybe Laura Nyro too. But no, it's not a common thread at all. It's interesting how the whole idea of an artist playing the piano and singing really started and ended with Schubert, because he was known to sing his own songs. I don't think Wolff sang his own songs. So maybe I'm picking up from a tradition that never really got started.

Have you been influenced much by Randy Newman's early stuff?

I only heard that stuff later, after having worked with Van Dyke Parks. I was always trapped in my classical dream world. I was like Elsa from [the Wagner opera] "Lohengrin." I've since heard him perform and listened to those albums, and they're incredible. I think it's often the case that people don't listen to the songwriters who are most closely related to them.

Nilsson?

Same thing as Randy Newman. I tend to like to listen to stuff, not necessarily that I identify with personally, but that I can sort of steal from. Which is why I listen mostly to classical music, because you can steal so much and no one will notice it.

One more try: Burt Bacharach?

Actually, that is a great influence. For me, Burt Bacharach is in a class all his own. Recently I had dinner with him. We were at the same dinner, but he knew all my music and was a fan of mine, and very, very -- how can I say it? -- personable about it. It was great.

In terms of contemporary pop, what do you like?

I like Chicks on Speed. I actually really love electroclash. On this record, I make a little fun of it, but I'd far rather go to see an electroclash show than go see countless other losers.

Do you listen to Radiohead? Someone walked in while I was playing your new album, and they thought it was Thom Yorke.

I love Radiohead. I went to see them at the Field Day thing, in the rain [at Giants Stadium in New Jersey], and it was worth every drop. It was amazing. They're really the best band around.

In terms of songwriters, are there people working now who influence you?

I'm very influenced by my sister. We have an ongoing rapport, partly based on jealousy, partly on love. We kind of spar with songs. I'm constantly amazed at the directions she takes, and the output she has, and the wealth of ability. And it is a real shame that she's not signed.

Are there some nonmusical influences on your work?

I went to art school for a while. I'm a big pre-Raphaelite fan. I was a big Brecht-Weill fan. I love Nabokov. I love his autobiography. But I'm a real culture vulture. I'm interested in what's playing at the symphony, or what's at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It seems you're mostly a high-culture vulture.

Yes! A culture falcon.

Have your lyrics been influenced by poetry?

Blake, Rimbaud, Baudelaire. I do consider Cole Porter and all the Tin Pan Alley or Great White Way New York songwriters to have been poets. Master poets.

When you first started singing, were you consciously trying to sound like an operatic tenor, or did your voice just develop naturally?

I wanted to be an operatic soprano. We're talking Renata Tebaldi here. I really do believe that my voice is another person or something. It's like a separate entity from my life, and one of the reasons that I've been so unsuccessful at romantic relationships is that I'm living with Maria Callas inside me, in my lungs.

A very unstable person to be living with.

Yes, very unstable and very demanding -- and on the other hand very fulfilling. I can always just sing a song and feel better afterwards.

The late Jeff Buckley is someone who, in a very different way from you, played with kind of operatic vocalizing. Do you like what he did?

I have a real story with him. When I first came to New York a long time ago when I was about 17, I had recorded my demo and I was bringing it by all these cafes, especially Sin-é, and this was when Jeff Buckley was just starting to rev up. And they refused my tape three times. So I hated Jeff Buckley. I didn't get it at all, and I thought he was an arrogant fuck, and I just didn't want to know about it. And it was a real failure, that first time I came to New York. I had to go back to Canada because I couldn't stand working at a movie theater anymore. I felt as if Jeff Buckley had defeated me in this weird way, without him even knowing it.

So then I went away and I developed my own thing, and got signed and returned to New York. And then one night I was singing a show, where the sound system had crapped out, so we were using an amp onstage, and it sounded weird coming out of the amp. And Jeff Buckley actually got up out of the audience, walked onstage and rearranged it and fixed things, and sat there curled up around my amplifier while I was singing. It was just a few months before he died, so he was not in a good state. And then we hung out later that night. It was my first lesson about measuring your ambition against other people, because he was just so weak. He was just the antithesis of what I thought he would be. I really felt bad for having had that attitude. And then he died, two months later, and I still didn't get totally into his music, I think because of trepidation. And then I had to sing "Hallelujah" for "Shrek," and I recorded my version before hearing his version, and then I heard his, and it just dawned on me at that moment the incredible loss, and the incredible talent that he was. The opportunity for me to sing with him would have been mind-blowing.

What happened to your singing between the first and second albums? It's such a different sound.

Well, I wasn't drinking as much, or doing as many drugs.

By the second album?

Oh, you mean between the debut and "Poses"? Oh man, you should hear my older tapes. My demos when I was 17? It's a wonder that I got signed. I sounded kind of like Kermit the Frog. I think what really changed my singing between those two albums was touring. I'd never toured for long periods of time. Singing every night. That was the key.

On this new album, you seem to be reaching toward higher, more vulnerable-sounding singing. In the past, you always kept such a full-throated sound going.

I think a lot of that has to do with my life. I really do feel like when I started writing this record, I was sort of subconsciously drowning, and I had to sing in a high register to pierce through the murkiness of everything. And in turn, it was kind of like self-sabotage. It made me realize that if I didn't get my act together, I wouldn't be able to perform this material, because it's really demanding. So I think in a lot of ways, my songwriting saved my life.

How consistently do you write?

I'm always writing. I've always got about four or five songs on the go, and I chip away very slowly at all of them, and then one day I'll have finished five songs.

The vast majority of your songs are written in the first person, and often seem to be based pretty firmly in often painful personal experiences. But not many people would call you a confessional songwriter.

Probably because I'm gay, therefore I can't go to confession. But a lot of the songs that I write are kind of what should be happening, what is meant to happen. If I did all of a sudden, during this conversation, stand up and sing to you -- in that context my song becomes a bit of a weapon, and a tool to get what I need. So I need to use every trick in the book to make it effective.

Most of your songs seem to be realistic, in that the events could have or did happen to you. But they're also very poetically worded.

I think a lot of it is based on visual stuff. For me the immediate lyric or vision or sensation is the most powerful and palpable in my work. I really want people to see my songs, instead of just hearing them. That's probably why my love of opera is so great. There's such an atmosphere surrounding the works, and so much visual content.

String parts and arrangements often seem really integral to your songs. Do they usually occur to you as you're composing, or are they added later in the process?

I always have a little bird on my shoulder that's singing, you know, the Berlin Philharmonic. A lot of the lines I think of previously, but a lot of that basic string padding I get someone else to do at this point. But, yeah, I do tend to think in terms of an orchestra in my head. I wish I could think like a pop band.

So you keep returning to classical references. Do you consider yourself at this point to be working at a kind of midpoint between pop and classical, or to be just a pop musician who is influenced by classical?

Well, I'm definitely airing the fact that I want to write an opera someday. Otherwise I would die an unhappy person. I don't think I would just dive headlong into a classical career. In all honesty, I don't have the chops, and I don't have the technical knowledge.

Have you started working on that opera?

I take jabs here and there -- definitely after this series of records, the first and second ones, and then these two ["Want One" and "Want Two"]. They're so centered around my personal life and my interior struggles, or my views on the world, that I would just love to work on something that is completely apart from my own life. An opera will be natural for me, because I do think that my life has been operatic, and I do view the world in very dramatic terms.

I'm always so shocked how few musicians make use of classical references. There's so much there. I mean, like a thousand years of music there that's really brilliant. I'm shocked by how little it's used.

Do you listen primarily to classical music?

I do. Mostly opera, and some symphonies. I'm still pretty entrenched.

How far did you get as a classical pianist?

I studied the piano for years, and I went to a conservatory, but I was always at the bottom of my class. I like to keep it that way, not to get too proficient in classical music, so I can always keep that awe of it, and that respect.

Do you still play classical stuff on the piano? Like for yourself?

I know a few little pieces. I'm really into Berlioz right now.

Actually, Berlioz reminds me of your music, in that it can seem so bombastic on the surface, but when it works it actually becomes very intimate, despite all the orchestral fireworks.

Well, I'd like to see a connection there! If you see one, then I see one too. I love Berlioz so much. For one thing, he really revolutionized the orchestra. The other thing I love about him is that he always wore his heart on his sleeve, in terms of his dire passion for culture and art. I really miss people like that in the pop world today. I don't see a lot of people who are about to slit their throat for the perfect chord or something.

Yep, you're all alone on that one. You haven't mentioned Chopin in any interviews I've seen, which surprised me. Is he not full-blooded enough for you?

I have a distinct memory, as a really young boy, maybe around 7 or 8, discovering Chopin and listened to him for hours on end in my mother's bedroom. Probably, from years of failed piano lessons, I sort of shied away from that. Honestly, I think he's incredible, but it can get a little schlocky. The one who I love right now who is schlocky but who I find amazing is Tchaikovsky. I'm a big Tchaikovsky fan.

So Verdi, Berlioz, Wagner, Bellini, Tchaikovsky. Quite the Romantic lineup.

Yeah, but I love a lot of the older ones too. Rameau, Massenet.

In the contemporary classical world, though, the kind of high Romanticism that you favor is kind of out of fashion. If the current classical scene were less minimalist or spectralist or whatever, would you consider getting more heavily involved in it?

Definitely. I'm more attracted to the classical world when it was a real popular art form, when it had a real connection to everyday people, and when it was about hits. I certainly admire a lot of contemporary classical composers, like Arvo Pärt or Gorecki or David Diamond. But really, I just like a good tune, in the end.

So how is "Want Two" going to be different from "Want One"?

I wanted at least the first part of this project to make it into Wal-Mart, and not have any major strikes against it. Mostly it has to do with subject matter. "Want Two" has a song called "Gay Messiah" and another one called "An Old Whore's Diet." So it's a little racier, a little darker. I feel almost like I've led people up to a cliff. Very operatic in that way. But still, all these songs were written and recorded in the same period.

Did you originally want to release them as a double album?

Originally that was my idea, but now I'm very happy with this approach. I don't want to burden the listener with too much Rufessence.

You talk about wanting to get the CD into Wal-Mart. How important is real pop-star success to you at this point?

Well, I think it's more of a game that I'd like to win. Because I do believe in the duty of an artist to improve culture for the populace. And I do find that right now there's just not enough edification going on, or enough variety. There are no choices out there anymore for kids. But I used to take it a lot more personally. Now I don't take it personally at all. And for this project, mainly considering my age -- I mean, I'm 30, which is pushing it for a pop star -- I really feel like it's now or never in that whole realm. But in terms of whether I make it or don't make it in that realm, there are other, bigger issues in my life.

You have worked with three fairly distinctive producers, but the albums all come out sounding like you. I expected the new album to be filled with all the little electronic sounds Marius de Vries likes to use, but there are relatively few of them.

Marius is a true producer in the sense that he produces the album that the artist wants to make. He had no qualms with me bringing in an orchestra, or whatever I wanted to do. I fought against producers for the first two albums, only because it's my natural leaning to chart out the recording studio as if it was Belgium and I was Napoleon. But Marius was really excited about all the things I had to bring to the table, which makes him a really great producer. He could work with any artist, I think.

Let's talk about Levon Helm [drummer from The Band] and Charlie Sexton [guitarist from Bob Dylan's band], who are on this album. They're sort of like red herrings, aren't they? Their presence was heavily publicized, and it seemed like a sign that you were going to go a bit folk-rock. But Helm plays on just one track, and even though Sexton is on much of the album, it's not very guitar heavy. It's even less folkie than what you've done before.

With Levon Helm, first and foremost he's one of the greatest living drummers, but also he does live in Woodstock [N.Y.], and we were recording there, so he was around, so it made perfect sense. With Charlie Sexton, what happened is that I had originally been thinking of doing this record with just a band. And then I went to see Dylan in Newport when he went electric -- I mean, the 30th anniversary of when he went electric. And Charlie Sexton was in his band. And I originally thought that maybe I would use Dylan's band. You know, just let him do all the work for me. It didn't work out that way, but I knew that Charlie Sexton was a big fan of mine, and needless to say he's easy on the eyes. It gets cold up there in Woodstock!

Last question: Was it weird having your mom sing backup on a Nick Cave album? Are you a fan?

I love Nick Cave. I'm sort of Nick Cave's good twin brother. We looked very similar at one point, when my hair was long. There was a striking resemblance. Together we're like the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

Shares