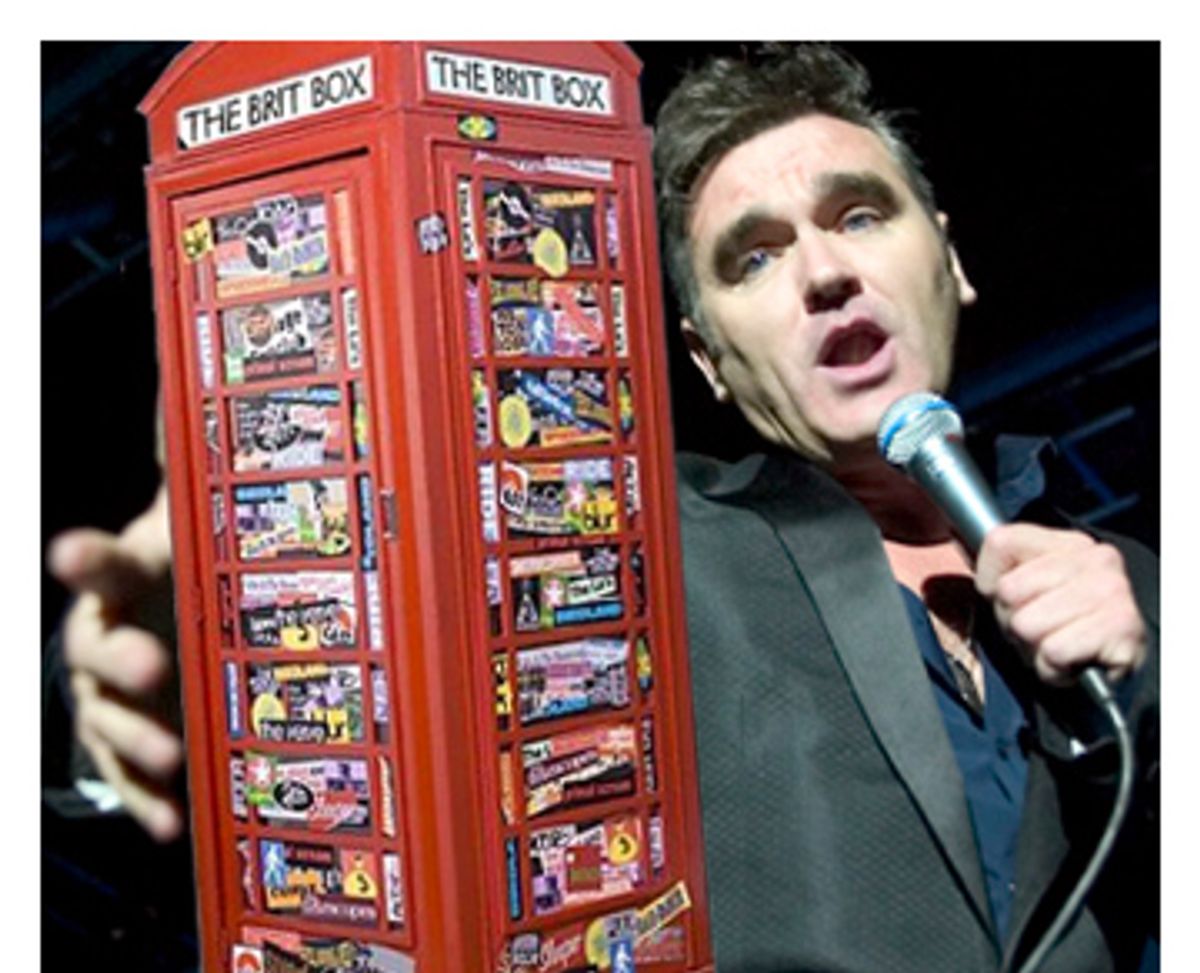

"The Brit Box: U.K. Indie, Shoegaze, and Brit-Pop Gems of the Last Millennium" (Rhino) comes cutely packaged in a tall red telephone box, the kind you've seen in countless old movies set in England. Of course, in the U.K., the classic public phone box -- somber scarlet paint, Her Majesty's crown insignia at the top -- was long ago replaced with a sleeker, modern-looking model. Besides, everyone uses cellphones now. But the out-of-date packaging suits "The Brit Box's" sales pitch to a T. The idea here is that Great Britain is quaint but classy. Just as Fortnum & Mason continues to offer afternoon tea long after the custom of eating scones and cucumber sandwiches died out among the populace at large, British bands can always be relied on to serve up the country's traditional pop values -- wordsmith wit, shapely tunes, English charm -- just as they did back in those fab 1960s.

In America, this shtick appeals to the same sort of Anglophiles who fasten on the British accents in Masterpiece Theatre and PBS's other imported programming (the dowdy costume dramas, lame sitcoms, and sleuth shows about crime-solving antique dealers and spinsters) as a seal of quality. Rock Anglophilia's constituency is a younger subset of the exact same demographic (college-educated upper middle class), and it's based around an identical syndrome: the equating of England with a superior level of refinement and literacy.

For a certain kind of American, being into pop music from the U.K. has long been a way to express a sense of being different from everybody else. The seeds of this dissident taste might germinate with hearing Depeche Mode or Morrissey on a modern rock station, then bloom through discovering college radio and being initiated in Anglo esoterica like XTC or Robyn Hitchcock, and finally blossom when the budding Anglophile starts picking up pricey import copies of British pop papers and magazines. English music weeklies like the NME have inducted American Anglophiles into a fabulous world where bands talk better (reared on the music press, they know how to give good interview) and look more stylish than their American indie equivalents. The British groups usually contain at least one or two pretty boys -- pale, thin, with really good hair, and maybe even eyeliner. Anglo androgyny appeals to young women and men who prefer their pop fantasy object to be sensitive and delicate -- not a buff hunk. Even U.K. frontmen who are considered macho louts in their homeland exude an aura of androgyny by association over here.

Aimed squarely at American Anglophiles, "The Brit Box" covers the years 1984 to 1999, a seemingly arbitrary time span. What actually distinguishes those 16 years as a separate period from the epoch of British guitar-based music that preceded it? Perhaps it's simply the fact that, notwithstanding its cult following in this country, almost all of the music on this box failed commercially in America. From the early '60s to the early '80s, what was big in Britain was, with a precious few exceptions, equally big in America: Beatles, Stones, Kinks, Who, Cream, Sabbath, Zeppelin, Rod Stewart. The Transatlantic traffic faltered slightly circa punk, but resumed in force with the Police and the Clash, followed by the synth-wielding, MTV-friendly androgynes of the early '80s, the so-called second British invasion led by Duran Duran. With a few exceptions like the Cure and Oasis, what this Rhino box documents is the British non-invasion.

Of course, "The Brit Box" doesn't attempt to encompass all the music that came out of the U.K. between 1984 and 1999. Plenty of English acts enjoyed substantial success in the United States. Tellingly, though, almost all of them --from George Michael to Soul II Soul, Simply Red to Stereo MCs -- were deeply steeped in black American music. Essentially, they represented the continuation of what the British Invaders of the '60s started, the great English love affair with cutting-edge black music: back then, blues and soul; by the '80s and '90s, funk, disco, hip-hop, house. However much they expanded and mutated their black sources, every major group of the British '60s was at heart a dance band, with years of playing in sweaty clubs to teenagers looking to shake their stuff. Anglophiles would probably argue that British indie rock of the '80s and '90s failed to find success here because of the conservatism of American radio. But maybe the failure of U.K. indie, shoegaze and Britpop comes down to these genres' gradual divorce from black music. Fetishizing the guitar sounds of the '60s, they forgot about its rhythmic base and impulse toward sonic hybridity.

The Smiths, who kick off "The Brit Box" with their 1984 song "How Soon Is Now," were a critical force in the drift away from the dance floor and black influences. Morrissey's voice sounded "pale" and "pure" in a way that was almost, but not quite, folky; Johnny Marr's guitar harked back to Byrdsy jangle rather than Chic's choppy funk. In 1986, the Smiths spelled out their opposition to mainstream dance-pop with their single "Panic," whose chorus demanded "burn down the disco/ hang the blessed deejay." For Morrissey, the DJ's crime was lyrical vapidity and complacent hedonism: "the music that they constantly play/ says nothing to me about my life." His interview comments of the time -- he described hip-hop's presence in the charts as "a stench," dismissed reggae as "vile" and derided R&B's gross caricature of sexuality -- prompted some critical supporters of soul music and club culture to argue that his remarks exposed a subtle form of racism in the indie music scene. Bizarrely, this ancient controversy flared back to life last month when Morrissey, interviewed by NME, blamed the erosion of the England he knew and loved as a child in the '60s on immigration, even using the classic nativist metaphor of a culture being swamped. During the resulting furor, Morrissey insisted (as he has before) on his opposition to racism, which he described as "silly."

This apparent contradiction -- being anti-racist but steadfastly avoiding any contact with black music culture -- is integral to indie rock. Indie-rock fans, with their high quotient of college students, may actually be more likely to have progressive political opinions than regular folks. But there is a blinkered parochialism to indie rock taste whose net result ends up looking an awful lot like self-segregation. One of the dirty secrets of the U.K. music press was the fact that sales figures and market research both showed that issues featuring black artists on the cover sold poorly. The charitable interpretation of this is that the regular readership assumed that these were performers in hip-hop or R&B, genres they either had no curiosity about or actively despised.

During much of the period covered by "The Brit Box," I worked as a writer on the weekly music paper Melody Maker, witnessing the rise of most of the bands featured herein. With a handful of exceptions -- the epoch-defining Smiths and Stone Roses, the dizzyingly innovative My Bloody Valentine, the witty, charismatic Pulp -- my attention was focused on other music going on during this period: rock's experimental fringe, hip-hop, dance culture and electronic music. When it came to guitars, I found the stuff coming out of America far more appealing, on the whole -- wilder-sounding, better played, often coupled with a deranged and scabrous sense of humor -- as purveyed by bands like Hüsker Dü, Big Black, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Butthole Surfers and Pixies. There was a palpable difference in quality and substance between American and British rock, audible on the basic level of rocking -- something few U.K. guitar bands seemed able to pull off during the '80s.

That's one reason why the bands corralled on "The Brit Box" stumbled when they reached the shores of America. Time and again, U.K. bands used to playing in huge venues to fervent crowds would arrive here to face the humiliation of starting all over again at small clubs to audiences with a high proportion of skeptics. Having risen so effortlessly in their homeland, the English groups would flinch at the prospect of slogging around the United States the way American bands did, at putting in the work required to make it here.

There was another reason for Brit bands' not making a serious bid to conquer the American market, though. In the high-turnover, hothouse atmosphere of the U.K. scene, being out of the country and out of sight means out of mind. British music fans and British music papers love the idea of the local: Fans want bands they can go and see regularly, groups they can root for and support almost like a soccer team. What the music press readership in the U.K. has always wanted is a band that resembles itself, which means it's got to be white, male, British. The band also needs to stick to the traditional format of songs plus electric guitars, and to lyrically offer a slightly heroicized version of the fan base's dreams and fears. If you look at what the readerships of NME and Melody Maker voted for as best band over the last 30 years, it's pretty much a straight line running from the Jam, Joy Division and Echo and the Bunnymen, through the Smiths, Oasis and Blur, right up to today's Franz Ferdinand and Arctic Monkeys. Not an American accent, black face or pair of ovaries in the lot of them. And apart from Oasis, not a full-blown American success story among them either.

* * * *

Open "The Brit Box" and you'll find four discs embedded in two CD cases, each designed to look like an ashtray. (Smoking seems to be a crucial element of Britpop's semiotics, from Oasis' "Cigarettes and Alchohol" to Arctic Monkeys' debut album with its cover photo of a lad smoking a "fag" down to its nub.) The phone box theme of fusty English charm resumes on the CD inserts, which depict baked beans, Licorice Allsorts, used teabags and a Beefeater Doll.

Pop Disc 1 into the CD player and it becomes apparent that, circa 1984, British indie rock averted its face from the present and looked back to the '60s. Alongside the Smiths, the prime instigator of this drastic shift was the Jesus and Mary Chain. By the time of 1987's "April Skies," included on "The Brit Box," the band had stripped away their sole claim to radicalism -- that trademark wall-of-noise -- to reveal classically contoured songs constructed in homage to a canon of renegade rock: the Stones, the Stooges, the Velvets, the Beach Boys.

Starting out at roughly the same time as J&MC but slower to achieve renown, Spacemen 3 engaged in a similar retreat to rock's archives. Their "Walkin' With Jesus" is little more than a guided tour of their record collection. The band consciously saw their music as a gesture of defiance against the '80s: In the box set's booklet, the band's Jason Pierce declares, "We sat the '80s out, really. We weren't in tune with what was going on musically or politically at all." Spacemen 3's mission statement was "taking drugs to make music to take drugs to." But on a popular level, the true revolution in late-'80s British music didn't take the form of Detroit 1969 revivalism. It was rave culture, fueled by ecstasy and soundtracked by the machine beats of house and techno, a music movement oriented around looking-to-the-'90s futurism rather than pining-for-the-'60s nostalgia.

Some of the J&MC and Spacemen's 3 indie fellow-travelers realized this and tried to board the rave train. The Stone Roses already had one of the few really groovy British drummers around, audible in the spring-heeled bounce of the otherwise '60s-sounding "She Bangs the Drum" (their contribution to "The Brit Box"). But as their hometown, Manchester, became the north of England's dance mecca, the Roses made a concerted attempt to assimilate house music's hypno-feel in their biggest hit, "Fool's Gold." Happy Mondays, also from "Madchester," started out resembling a funked-up Velvet Underground. Then they hooked up with U.K. house producers for songs like the one included here, "Step On" -- but their lumpen groove generally sounded more club-footed than club-friendly. Just about the funkiest track on all four discs of "The Brit Box" is "Loaded" by Primal Scream, the group fronted and led by Jesus and Mary Chain's original drummer, Bobby Gillespie. But that's because it's a remix by DJ-producer Andy Weatherall, who transformed what was originally a bluesy ballad into a house music update of "Sympathy for the Devil."

"Swing" and "feel" are in short supply on "The Brit Box." This is partly due to the lingering influence of punk, which treated virtuosity as something to be avoided. British rock once boasted many of the finest drummers in the world -- Keith Moon, John Bonham, Charlie Watts, Ringo Starr, Ginger Baker ... the list goes on. But it's hard to imagine anyone other than die-hard fans being able to name the drummers in the vast majority of bands on "The Brit Box." Rarely contributing anything to the music beyond marking time, the drummers mostly seem to be there because that's what rock bands are supposed to have. Anybody in Britain who really cares about beats and has a feel for the construction of that commonplace miracle, a groove, has long since gone to work in dance music or hip-hop.

In the absence of rhythmic verve, Britpop's saving grace is melody. Perhaps the traditions of Tin Pan Alley and the music hall have always been stronger in the United Kingdom. After all, we got rhythm secondhand, as an American import, starting with jazz. Rock 'n' roll and rhythm and blues impacted the U.K. so hard in the '50s and '60s that the result was a perfect balance between beat and song. But with some of the lesser output of '60s England -- all those Merseybeat groups like Freddie and the Dreamers, bands like Herman's Hermits and the Hollies -- you can hear a native proclivity for over-melodiousness, the musical equivalent to the national sweet tooth. You can hear the same weakness -- an eager-to-please mellifluousness of tone and tune -- in a lot of the Britpop on this box. That said, melodic jewels are scattered across these four discs, like The La's "There She Goes," or "Here's Where the Story Ends" by the Sundays, whose singer Harriet Wheeler fused Morrissey's plaintiveness with the enraptured grace of the Cocteau Twins' Liz Frazer. Frazer herself appears twice on the first disc, on the Cocteaus' slightly froufrou "Lorelei," and then as the backing vocalist on Felt's "Primitive Painters," a transcendent anthem of defiant apathy.

Felt's "defeatist attitude" was an advance glimpse of the shoegaze scene, aka "dreampop." The term "shoegazer" originated from these bands' withdrawn aura onstage. Guitarists, especially, seemed to spend the whole gig staring at the floor. There was a prosaic reason for this: The billowing amorphousness of shoegaze's guitar sound relied heavily on foot-controlled pedal effects. But the shoegaze bands' seeming inability to meet their audience's gaze captured the essence of this neo-psychedelic genre, which involved escaping from a troubled world into a narcoleptic dream-state. The sound was pioneered by My Bloody Valentine, who just last month announced their return to activity after 15 years' hibernation and whose legendary stature makes them something of the Pitchfork generation's own Velvet Underground. Their string of classic EPs and two masterpiece albums dwarfed the efforts of their progeny. But the most successful shoegaze band was Ride, regular visitors to the U.K. Top 20 who prospered seemingly for their very mediocrity.

I enjoyed shoegaze quite a bit at the time, but 15 years on, listening to this stuff feels less like bliss-out and more like being lost in a listless mist. Rather than dreampop, Lush's "For Love" resembles a song the band dreamed but could only faintly recall upon waking: bass inaudible, drums soft as snowflakes, voice partially erased, guitars like a watercolor with too much water. The anemia deepens with the sickly Chapterhouse and the perfectly formulaic Curve. Hardly forceful presences to begin with, shoegaze vocalists were further subsumed by the genre's standard production style, which buried their voices beneath layered guitars.

With its aesthetic of surrender, shoegaze's dream-your-life-away resignation mapped neatly onto the U.K.'s political situation. The Tories, under Thatcher and Major, pursued youth-unfriendly policies like phasing out grants to university students, and shifting the local tax burden from property owners to young renters. There's a curious aptness, too, to the way that so many young people during the '80s and early '90s went into a kind of cultural exile by hiding in "the '60s" (the music of Byrds, Velvets, et al.) just as Thatcher and her allies were steadily abolishing the gains of that decade.

Eventually the U.K. scene snapped out of the dream haze with a concerted move toward punchy tunes, clarity of production, and singers who reveled in the spotlight. First came the punk recyclers (amphetamine-gobblers These Animal Men, protest poets the Manic Street Preachers). Next up was the glam redux of Suede, massive for a couple of years and deservingly so, although "Metal Mickey," their "Brit Box" offering, is one of their flimsier singles. All this was just preparing the way for Oasis, though. When "Live Forever" rips out the speakers halfway through Disc 3, you can see why they had such an impact: What a relief to hear a voice that snarls, that takes the tune by the scruff of its neck. Oasis understood rock as a matter of attitude and vocal timbre (Liam Gallagher's insolence) combined with guitar sound (brother Noel's distorted tone, gnarly enough to sound classically rock but stopping well short of shoegazey miasma). The idea of rock as a rhythmically dynamic music was simply forgotten. Oasis' drummer never did much more than trundle unobtrusively beneath the singalong; Liam's voice dominated the mix.

The British scene let out a massive sigh of relief: After shoegaze, Oasis had redirected indie rock back to the eternal verities of songs. Thrilling as "Live Forever" and the group's five or six other killer tunes are, though, one shouldn't lose sight of the Gallagher brothers as culture criminals -- the guys who nearly killed for good the idea of rock as a genre that was forward-looking and experimental. (That notion made a slight recovery with Radiohead, a band who the Gallaghers, revealingly, find an almost personal affront.) Oasis paved the way for a grim phase of U.K. pop dominated by what some wag nicknamed "Dadrock" -- bands like Ocean Colour Scene, Cast, Kula Shaker and Dodgy. It was Dadrock because it could be (and was) enjoyed equally by kids in their teens and their parents, who had been in their teens or 20s back in the '60s, whence these groups derived all their ideas. But when you compare Britpop with its '60s source, it's striking how uninspired most of the later bands sound as musicians; how little flair or aspiration is audible on the level of the playing. Mostly what you find on Discs 3 and 4 of "The Brit Box" is sustained competence.

There are diamonds in the dung heap, of course: "Stutter," Elastica's homage to 1978, the year of Buzzcocks and Wire; Supergrass' T-Rexy youth anthem "Alright"; the Roxy Music-influenced tumult of Pulp's "Common People." These tracks, from the prime period of Britpop (1994-96), capture the optimism and confidence of that moment when everyone in Britain knew that the Conservatives were going to get kicked out by Tony Blair's New Labour at the next general election. Blair courted the leading Britpop bands both before and after that May 1997 victory, making the revitalized U.K. pop scene a central part of his "Cool Britannia" push to rebrand the nation as modern and vibrant. He praised Alan McGee of Creation, Oasis' record label, as a shining example of New Labour-style entrepreneurialism, and famously invited McGee and Noel Gallagher to a reception at 10 Downing Street.

"Cool Britannia" was a replay of the '60s "London Swings" scenario. Egos inflated by their importance in the scheme of things (and by vast quantities of cocaine), Oasis then made the bloated "Be Here Now," whose lead single -- "D'you Know What I Mean" -- attempted to capture the weightiness of the historical moment with its incoherent chorus "all my people right here right now/ you know what I mean."

There were much more interesting things going on in the U.K. during this period, which "The Brit Box" acknowledges with tracks from Saint Etienne, Stereolab and Cornershop. Saint Etienne presents a far more attractive version of pop Englishness than the rehashed Kinks/Beatles/Jam of most Britpop. In their hands, this was a national identity open to outside influences: house music from Chicago and Rimini; soft "lover's rock" reggae; French pop of the '60s. A similar cool, esoteric mix informed Stereolab's music, which blended trance-inducing pulse with incongruously non-lulling lyrics. On "Wow and Flutter" (included here) singer Laetitia Sadier coos of capitalism, "it's not imperishable, it's not eternal/ Oh yes it will fall." Cornershop were another politically aware bunch of smartypants, whose lineup includes two of the handful of non-white musicians on "The Brit Box," brothers Tjinder and Avtar Singh -- represented here by "Brimful of Asha," an oblique paean to Bollywood singer Asha Bosle.

These groups are exceptions to the post-Oasis rule. As we enter the last three years of the '90s with Disc 4, it's like every band is competing for the attention of buskers across the land. The musical backing is just that -- a mere backdrop for the voices, which are clear, soaring and prominently exposed in a mix that kicks everything else out of the spotlight. One reason for this is that for indie rock fans on both sides of the Atlantic, the raison d'être of the genre is clever lyrics. And in indie, "clever" often equates with arch turns of phrase or droll allusions to popular culture. Hence the "X Files"-referencing love song "Mulder and Scully" by Catatonia, a Welsh band whose 1998 album International Velvet (another pop culture reference) went triple platinum in the U.K. Catatonia singer Cerys Matthews was once unkindly but indelibly and accurately described as sounding like "a chicken laying an egg" by Neil Hannon of the Divine Comedy, whose own droller-than-thou "Brit Box" contribution, "Something for the Weekend," was inspired by actress Kate Beckinsale.

Flourishes of "wit" such as these were scant compensation for Britpop's sheer mundanity of sound as the decade's end approached. Ash, Bluetones, Hurricane #1, Rialto, Gay Dad -- there's a reason you've never heard of these bands. For reasons unclear, "The Brit Box" stops short of venturing into the new millennium, when a new, spiky vigor reappeared in the form of Franz Ferdinand, the Libertines, Arctic Monkeys, Art Brut and the Klaxons. Fans of well-honed, observational wordplay didn't need to deny themselves fully contemporary beats either, thanks to a new breed of British singer-rappers like Mike Skinner of the Streets, Lily Allen, Hot Chip and Lady Sovereign. Influenced by the rhythms and vocal stylings of ska, reggae, lover's rock and dancehall, these performers showed how fertile and enduring the contribution of Jamaican music has been to British pop across the decades.

Racists in Britain used to chant "There Ain't No Black in the Union Jack." Draping themselves in this flag, Britpop artists inadvertently sealed themselves off from the invigorating stream of new ideas coming from black music in the '80s and '90s, a good proportion of them -- genres like jungle and 2step -- spawned on Britpop's own doorstep. Cultivating their quintessential quaintness, clinging tight to a glorious and storied past, the British groups instead concentrated on appealing to patriots at home and Anglophiles abroad. But in the process they lost the world.

Shares