Forget for a second that we're talking about an animated short on Cartoon Network that airs around the witching hour, a time when not one kid in North America is burning the midnight oil -- at least not with his parents' permission. And forget also that we're talking about an ornithological superhero who wears a three-piece suit and litigates for a living.

Rather, pretend we're witnessing a bizarre discourse on popular culture, fictional systems (including their explosion) and psychosexual norms. Because it is then that Larry McCaffery's theories on metafiction and intertextuality -- the mechanisms of postmodernism outlined in his seminal work of literary criticism, "The Metafictional Muse" -- come into play. If, as McCaffery argues, "we inhabit a world of fictions and are constantly forced to develop a variety of metaphors and subjective systems to help us organize ... experience," then metafiction is the pomo tonic for our time, a Derridean (the name-dropping will end soon, I promise) playfulness that "becomes a deliberate strategy used to provoke readers to critically examine all cultural codes and established patterns of thought."

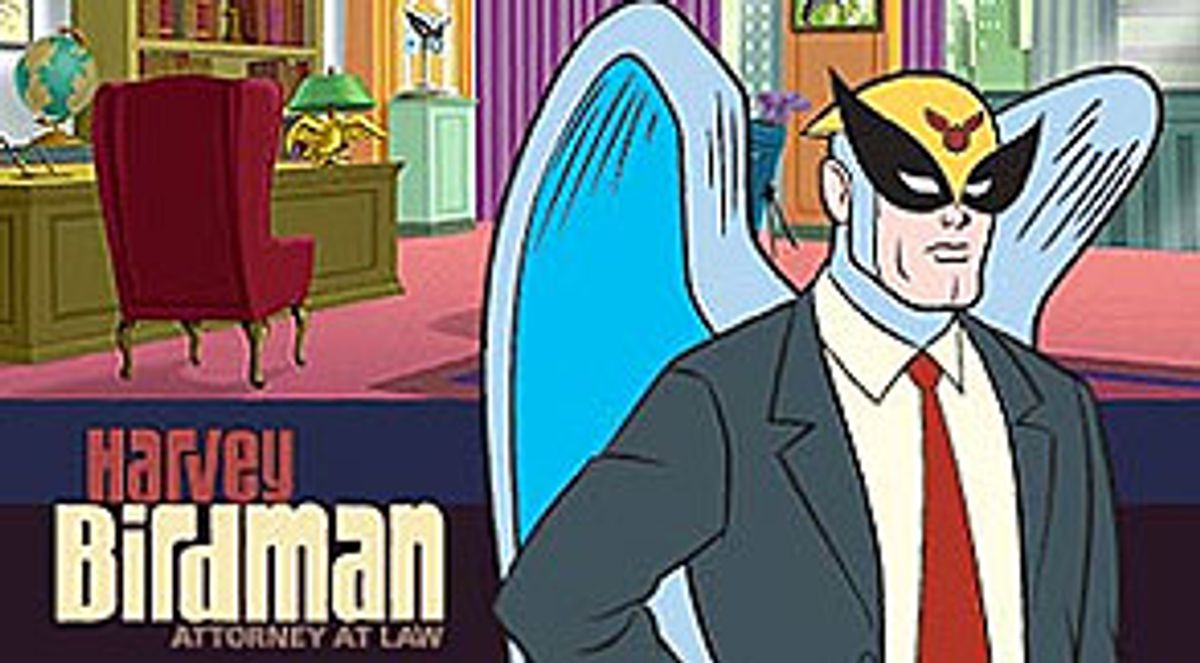

To get more specific, we're talking about "Harvey Birdman: Attorney at Law," the show that has reimagined Fred Flintstone as a Soprano-style mob boss, Scooby and Shaggy as potheads with the munchies (of course, we always knew that was true) and Yogi Bear's companion, BooBoo, as a gay radical terrorist. And that's just for starters. Michael Ouweleen and Erik Richter, the Ginsu-sharp creators of "Harvey Birdman" (part of Cartoon Network's "Adult Swim" block, which airs Mondays through Thursdays from 11 p.m. to 2 a.m.) are busy assaulting the previously "locked systems" (McCaffery again) of everything from classic TV sitcoms and dramas to Hanna-Barbera cartoons and famous movies. Birdman himself is a revision of a "third-rate superhero" from the obscure 1967 Hanna-Barbera cartoon, "Birdman and the Galaxy Trio." Everything old is indeed new again.

What McCaffery's pomo theorizing has to do with the outrageous "Harvey Birdman," which premiered a batch of three new episodes last week, depends on who's watching. To the adolescent who sneaked out of his bedroom to catch Cartoon Network's groundbreaking bloc of mature animation, it most likely doesn't ring a single bell. But to pop-culture fans immersed in the "Matrix" franchise -- a metafictional smorgasbord that draws on Jean Baudrillard and William Gibson -- it might have more resonance. If you're Richter and Ouweleen, it partially explains how and why your show is able to explode and reinscribe narrative convention and history at warp speed.

"It's weird how lightning-quick you see something on TV and have an immediate understanding of where it is going to go," says Richter. "You know what's going to happen. People who are watching immediately can fill in the blanks, and you don't have to take the time to actually show what happens. That formula allows us to take an off-ramp. Is that postmodernism? Probably. When we first started doing this it was like, 'Will anybody get what the hell any of this is?' And the answer is, not always! But we're trying. We're not trying to be intentionally obtuse. We're really trying to tell a pretty straightforward story most of the time."

"I've actually been surprised by the broad appeal of it," adds Ouweleen. "It's broader than I, for one, had thought. And you've got to give people credit. This is our common language, man, and people are really savvy. And so they can catch a lot of what we're referencing. We're not really setting out to do a lot of inside jokes, but when we tend to go a little bit more obscure I'm finding that people are following it. Big time."

That is most likely because there is literally so much to follow. Part of this deliriously intertextual show's broad appeal can be traced to the fact that it covers such broad territory, jumping from conventional cartoon to genre-busting experiment to inside joke, onwards and backwards, all in the span of about 15 minutes. That's one hell of a compression rate and, ironically enough, it is sometimes too much to take in one sitting.

"We are blazing a new path and, in a sense, we aren't," explains Richter. "'Adult Swim' is much more free-form as a bloc than anything on TV has ever been. But it's no different than 'Mystery Science Theater 3000' or you know, [the '70s comedy troupe] Firesign Theatre. It's just that now there's a corporate substratum that has allowed this to happen across a three-hour block of time -- and that's new. And if you tune in, you can be assured that, whether it's 'Home Movies' or 'The Oblongs' or 'Futurama,' it's going to be different and feel of a piece in a weird way. Because we're all kind of talking to one another."

Like a shotgun blast, "Harvey Birdman" explodes outward into postmodern reconfigurations. "The Dabba Don," referenced above, embroils the cast of "The Flintstones" in a mobster universe. Even minor characters, such as the various creatures that mundanely function as household appliances, are called to the witness stand to testify against Fred's illicit gambling and "white slavery" empires; "You're dead to me, can opener!" Fred shouts at one poor dinosaur that rats him out. Birdman himself, pressured by organized crime to defend Flintstone, ends up with more than one severed head at the foot of his bed; only one of them (Hanna-Barbera's Quick Draw McGraw), however, is a horse. Meanwhile, in the fan favorite "Shaggy Busted," Scooby Doo and Shaggy are unmasked as stoners, nabbed at the beginning of the episode in a live-action "Cops"-like bust as they drive down dank streets in their smoky van (Cheech and Chong's "Up in Smoke" anyone?) while blasting the opening riffs to the Doobie Brothers' (get it?) "China Grove." And that's just the beginning segment. We haven't even gotten to Birdman's opposing counsel, Spyro, a literal drama queen who phrases most of his arguments in Shakespearean meter (his version of Shaggy and Scooby's pot bust is titled, "As You Smok't It"). Or Hanna-Barbera bit player Magilla Gorilla propositioning Birdman in prison. Or the heavy-lidded montage featuring Scooby and company's various pizza binges and herbal appreciations. Or the bizarre resurfacing of a decades-old Tab commercial spotlighting Birdman's more-than-platonic relationship with his favorite one-calorie soda.

Then there's "Death by Chocolate," an episode that would make even McCaffery (who argues that a "bleak, absurdist comedy permeates the epistemological skepticism" of postmodern enterprises in "The Metafictional Muse") blush, this time starring Yogi and BooBoo Bear. While the plot line confirms Richter's assertion that "Harvey Birdman" is interested in telling straightforward stories, the episode is one extended, hilarious hallucination. Yogi's trusty (and usually much brighter) companion has metamorphosed into a Ted Kaczynski-type radical called the UnaBooBoo, and is nabbed in a government sting reminiscent of the Waco and Elián González debacles. The Waco jab may be a sly one; the government gives BooBoo 10 seconds to come out -- before launching an explosive at the count of two. But the Elián jab is more like a haymaker, replicating Alan Diaz's famous Associated Press photo of the closet invasion, with Yogi and BooBoo in the starring roles.

That satirical revision is literally over in the blink of an eye, but the same can't be said for the episode's absurdist ending: BooBoo and Harvey make love after a successful acquittal, only to have Birdman discover that the UnaBooBoo was indeed guilty of terrorizing his victims with booby-trapped gift baskets. If watching Birdman scrub himself silly in the shower to clean off his complicity doesn't cause heart-attack laughter, perhaps the slow-dawning realization that the entire finale of the episode duplicates the ending of the 1985 courtroom thriller "Jagged Edge" will.

While the show's conventional comedy is top-shelf, it is also these smartly satirical allusions that have earned it such a devoted audience, even when its own cast -- like Stephen Colbert from Comedy Central's "The Daily Show," who plays Harvey's boss, Falcon Seven -- has no idea what the inside joke may be.

"The beautiful thing is that I don't think Colbert had seen 'Jagged Edge,'" Richter says. But he had no problem understanding why his character would say, 'That's all right, it's over, baby,' to Harvey. Therein lies the secret. These guys don't ask many questions, and still get it. But what really shocked me more than anything is the various and sundry things that people respond to. Weird, unexpected things. It kind of illustrates the facets of the human mind, how people look at things. Not to call this art, but everybody's seeing something different. I guess that, initially, people got the 'Jagged Edge' reference. Michael and I have talked at length about this, just how funny it is that people have watched and responded to the show, as well as what they respond to. Some hate one thing and love another, and it's never the same thing that they hate and love."

"It makes sense and it doesn't," adds Ouweleen. "That's a goal. We're pretty conscious about making sure we're not just ripping structure apart for the hell of it or to be destructive."

Richter agrees. "We don't set out to be ridiculous. And yet there's some line between silliness and sense that's OK to cross. And we want it to make sense. It's weird, because we're squashing what normally -- probably on television -- would have been an hour format into 12 minutes. And we're always kind of struggling with it. It's an actual case of, how much of the old 'Perry Mason' convention do we stick to? And how much do we veer off into the 'Jagged Edge' thing? That's a constant discussion."

What doesn't seem to be in constant discussion, however, is the show's transgressive (and, many would argue, progressive) subject matter. Minute for minute, it's hard to find more sexual entendre on television, to say nothing of cartoons, than in any given episode of "Harvey Birdman." Its first episode features Race Bannon and Dr. Benton Quest, paternal figures to Hanna-Barbera's "Jonny Quest," as gay lovers suing for custody of their fair-haired charge and his Indian sidekick, Hadji.

The second episode, "A Very Personal Injury" finds Birdman defending minor Superfriend, Apache Chief, who loses his powers (unlike the flying Superman or the swimming Aquaman, the Chief can only "grow large") after he spills a cup of hot coffee in his crotch, rendering him, er, "small," as Harvey testifies. Birdman not only ends up in bed with the UnaBooBoo in "Death by Chocolate," he is summarily "man-kissed" in "The Dabba Don" and sexually embarrassed in an episode called "Shoyu Weenie" (rather than give graphic details, Ouweleen and Richter make a courtroom clown creep behind Harvey, blow up a phallic balloon and hand it to him).

OK, so the idea of exploding so-called sexual norms is found everywhere in postmodern intertextuality and metafiction. But -- other than the random Bugs Bunny drag scene in "What's Opera Doc?" -- it's rare on Cartoon Network. Which raises the question: How do they get away with it?

"The network doesn't ask 'Why?' an awful lot," Richter says. "We're in awe sometimes, to an amazing, astonishing and inspiring degree. The notes we'll get back are general. Like, 'Even for these shows, this makes no sense, so you might want to work on it.' Or, 'Just explain this a little bit more to make the leap easier to understand.' Or, 'I can't hear this line of dialogue.' But other than that, we don't have to explain much of anything to anyone. I watch a significant amount of television, and it seems to me that that is a rare and wonderful thing. Because there are many places where we would have to argue for things like this."

"From a standards perspective, they're trying to be very careful," Ouweleen adds. "They're trying to be on the safer side of 'South Park,' and that means we have to be smarter. We can't say or do certain things that they can do on that show, so we try sophistication. But what I'm more amazed by is the atypical stuff that we're allowed to do. Like the man-on-man kissing, which isn't so much a standards issue in my mind. It's more that they allow us to do it because it's just so weird."

For a show that invests so heavily in opening up what are fast becoming stagnant artistic conventions, especially in animation, the absurdly metafictional exercises of "Harvey Birdman" are, above all, deeply entertaining and decidedly surreal. That is, after all, what animation is all about.

"Anywhere else, you would have a conversation on how unacceptable this is," Richter explains. "But a fan of the absurd would say, 'Where do we start?' I would say the absurd begins with a lawyer walking around with wings poking out of his back. It's totally unexplained, like Harvey kissing a prehistoric cartoon caveman. In the end, they're all characters that straddle two worlds, that have human neuroses and cartoon problems. Is Harvey a real guy with problems that we all have, or is he an old superhero? He can be either at any time. And it's fun to bounce back and forth between them. It's a weird embarrassment of riches."

Shares