If you think Cormac McCarthy is a great American novelist whose every syllable is revelatory, you'll watch and no doubt love "The Sunset Limited" (Feb. 12, 9 p.m./8 Central), the new HBO version of McCarthy's stage production. This long conversation between a suicidally depressed, atheist college professor (Tommy Lee Jones, who also directed) and a devoutly religious ex-convict (Samuel L. Jackson) is a clearinghouse for many of McCarthy's favorite subjects: the collapse of civilization and decency, the struggle to be moral in a possibly godless universe, the impotence of philosophy and culture in the face of evil. And it explores its themes in a casual, at times rambling way that's not without charm -- especially if you imagine the characters not as free-standing, flesh-and-blood people, but as aspects of McCarthy's authorial voice: the intuitive, passionate man of action who's seen the worst of human behavior yet still believes in hope; and the tweedy, ruminating bookworm who's pretty sure civilization is on the express elevator to hell and doesn't see the point of pretending otherwise. Much of the piece has an informal, confessional quality that will be catnip to some viewers.

Not to me, though. As a devotee of live, televised theater productions from TV's so-called Golden Age, I'm happy to see any sort of halfway intelligent stage piece adapted for the small screen, especially when the filmmakers have tried to retain its theatrical flavor -- to keep it stage-bound and intimate rather than "opening up" the text with additional locations and infusions of "cinematic" action. The late Louis Malle ("My Dinner With Andre," "Vanya on 42nd St.") did this better than anyone, conjuring an almost uncanny level of involvement with nothing but tight close-ups of smart, subtle actors. Jones' direction is in that vein. But aside from a few intriguing sound design touches (train and plane and car noises; snippets of music from adjacent apartments and from the street below) it's rather plain and perfunctory -- an assortment of uninflected close-ups and wide shots that aren't deliberate or imaginative enough to make McCarthy's text cohere.

And I use the word "text" rather than "script" or "play" for a reason, because for all its noble intentions, and all its sincere interest in depression and optimism, godlessness and holiness, education and instinct, "The Sunset Limited" feels more like an assortment of notes and notions for a play rather than an actual play. McCarthy must have been aware of this; it's probably why he subtitled it "a novel for the stage" -- a description that sounds a bit like a cover-your-ass caveat, a way of redefining failures of vision, structure and focus as failures of imagination on the part of the audience. ("Oh, I understand why you would have a problem with this element or that element ... but this isn't a play, see, it's a novel for the stage!")

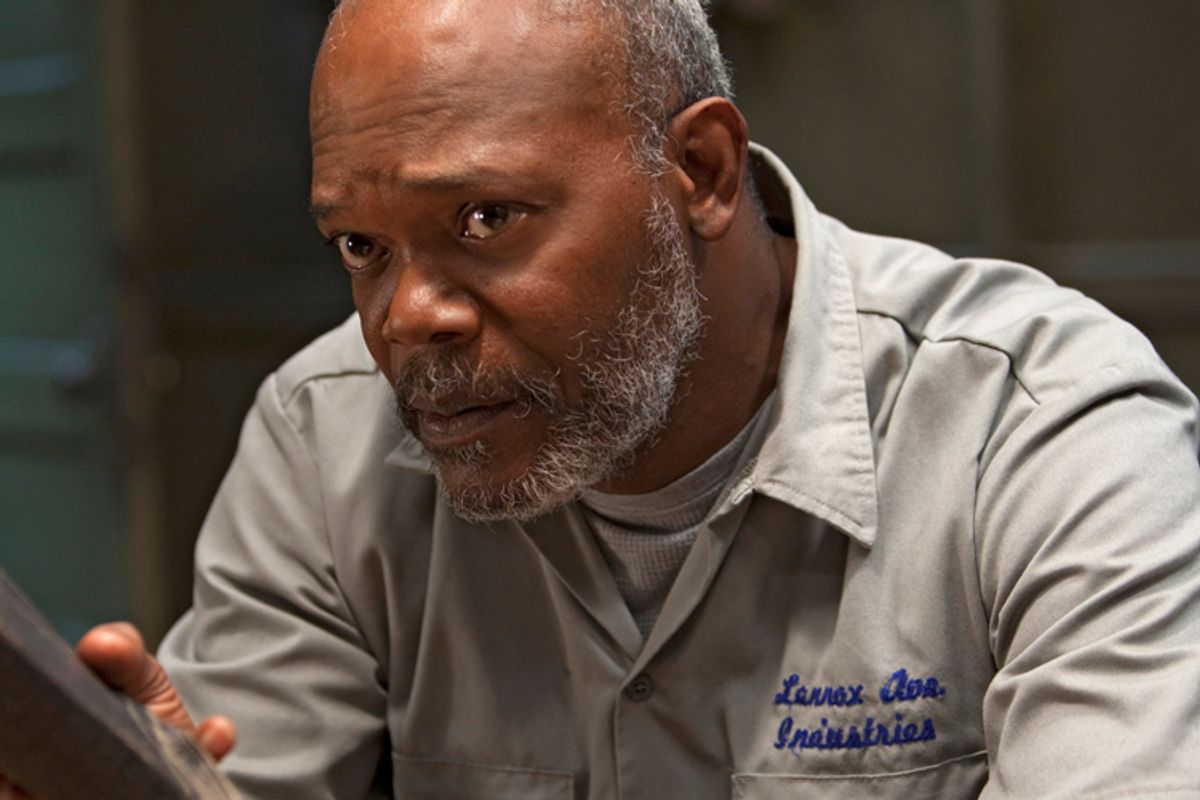

Jones' character is identified simply as "White," Jackson as "Black." At first this promises a tiresomely simplistic racial allegory -- and there are a few awkwardly undeveloped moments where White condescends to Black, describing his tenement apartment building as a hell hole full of dangerous, horrible people whose souls aren't worth saving -- but that's not where McCarthy is going with it. The color-coded names seem almost like ironic inversions of the characters' personalities and worldviews. Jackson's character, a one-time convicted murderer who saved the despondent professor from jumping into the path of an oncoming subway train and brought him back to his apartment to decompress, is a conscious optimist -- an African-American from the South who has read the Bible front to back and finds comfort and insight in it, especially in Jesus Christ's admonitions to love thy brother. Despite his character name, he's a source of light, of illumination. Jones' character, White, is a dark soul, a man whose prodigious book learnin' and ceaseless rumination on history has convinced him that culture is powerless in the face of ignorance, hatred and evil, and that the story of humankind is mostly grim. "The things I believe in no longer exist," he tells Black. "It's foolish to pretend they do. Western civilization finally went up in smoke in the chimneys of Dachau, and I was too infatuated to see it. I see it now."

Without putting too fine a point on it, Black lets White know that he believes himself an instrument of Jesus' will, a force of good. This is partly Black's way of doing penance for his days as a rootless, murderously angry drunk. (White repeatedly says he needs a drink -- a shot of whiskey to calm his nerves, a glass of wine with their shared meal -- but Black has no interest in alcohol, because he feels life doesn't need any enhancement, and because he's done a lot of drinking in his life.) But there's also a touch of Magical Negro-hood to the Black character -- as if he's a streetwise urban cousin of Clarence, the guardian angel who saves George Bailey from killing himself in "It's a Wonderful Life." And although McCarthy's dialogue insists that Black isn't that kind of cartoonishly benevolent figurehead -- and gives him some vividly brutal prison stories to prove it -- the character's weirdly anachronistic Old Wise Black Man dialect brings the character back around to caricature. ("You is read a lot o' books?" Black asks White. "You said you done read fo' thousand books?")

The racial coding of the main characters suggests McCarthy has a condescending white liberal view of African-Americans and Caucasians -- that the black man is the natural man, the instinctive man, the simple man who's in touch with his true nature, while the white man is burdened by education and philosophy and just flat-out thinks too damn much. This is incidental, by the way -- I'm sure McCarthy would be horrified that anyone would get that sort of retrograde message from his writing -- but that's what comes through. The simple man, the Natural Man, which is to say the Black Man Inside All of Us, is the only thing preventing the human species from thinking itself into such a depressed state that it wants to give in to the dark allure of the Sunset Limited (the play's poetic euphemism for death or annihilation). One can interpret the whole thing as allegory and argue that none of it is "really happening," that Black is a philosophical construct or symbol or manifestation of White's anxieties, or perhaps a spirit guide interrogating White in a purgatorial way station between life and death. (Whenever White tries to leave the room, Black stops him.) But this possibility remains frustratingly undeveloped.

There might be a good play, a good novel, a good movie, a good something, in all of this, but it doesn't come through on-screen. "The Sunset Limited" is a dog's breakfast of dramaturgy, interspersing brilliant bits with greeting-card wisdom, ostentatious philosophical throat-clearing, and an unseemly strain of self-congratulation. (The characters keep praising each other's well-turned phrases, and at one point Black is so impressed with one of White's lines that he writes it down.)

The actors are heroically invested in the material. Jones, who has spent much of his post-"The Fugitive " career playing almost comically confident he-men, pushes against type, portraying the professor as an intellectual paralyzed by despair (and by the realization that his education and self-consciousness only amplified it). Jackson excels at gregarious chattiness and bursts of passion and rage. He gives both talents a workout here. Black's monologue about a bloody fight in a prison cafeteria is one of the best pieces of acting Jackson has ever done, and he's equally effective in the quieter moments when Black acts as White's affable interrogator, seizing on telling words and phrases and pushing White to examine his premises.

But these aren't saving graces, just graces. "The Sunset Limited" doesn't have any action to speak of -- physical or dramatic -- just rhetoric and banter. I'm not convinced it would have been greeted as a noteworthy theater piece (hell, a play!) if McCarthy's name weren't on it; if it were written by someone else, someone less acclaimed and adored, "The Sunset Limited" might have been judged more harshly for its failures as both literature and drama. Everyone involved with this production obviously meant well -- this TV movie doesn't have a cruel or ignorant moment -- but good intentions aren't enough. If you want a focused, coherent, often heart-rending examination of the same themes, read (or re-read) McCarthy's "Blood Meridian," "The Road" or "No Country for Old Men."

Shares