In "Friday Night Lights," high school football isn't so much enthusiasm or even obsession as shared psychosis. I don't know how this material was presented in the H.G. Bissinger nonfiction book that is the source for the new movie, but in the film's first half, director Peter Berg, who co-wrote the script with David Aaron Cohen, presents football mania in tiny Odessa, Texas, as the embodiment of American win-at-all-costs mentality.

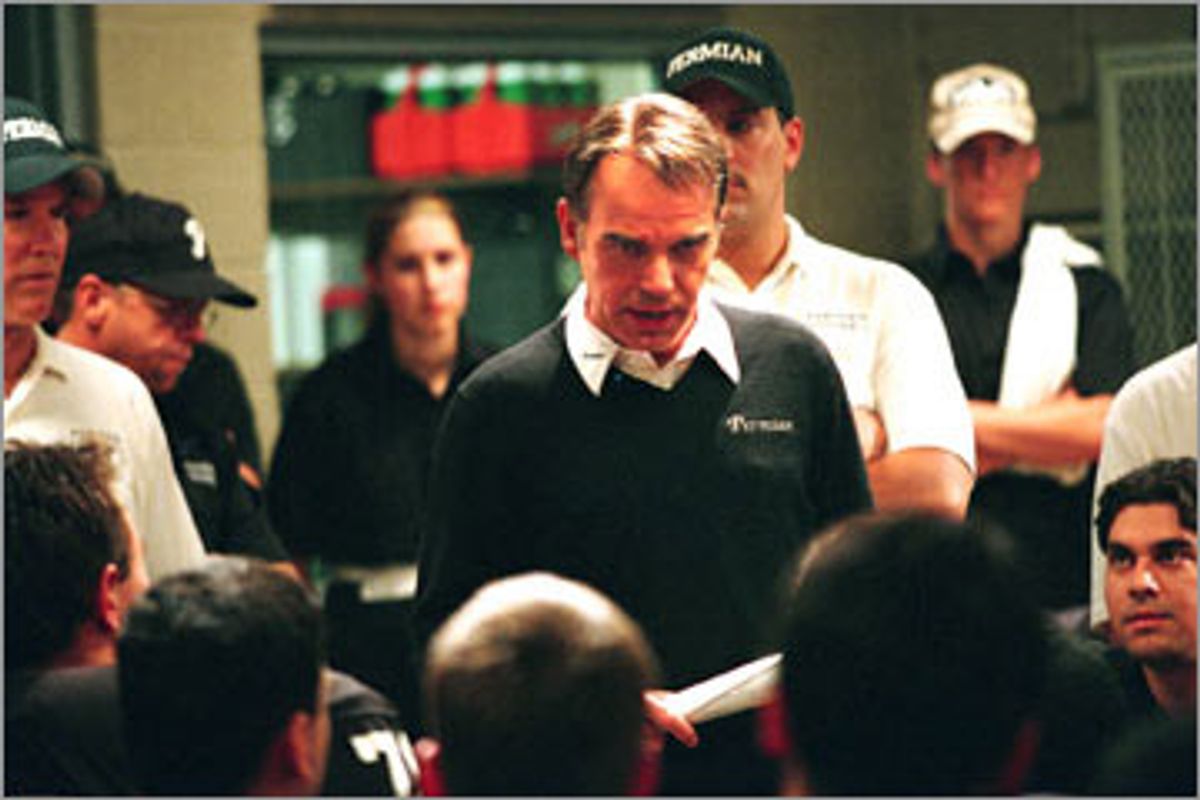

The town has diverted money from the school to build a stadium for its local team, and the new coach (Billy Bob Thornton) is paid more than the school principal. The kids on the team can't go out for a hamburger without someone coming up to tell them they can't let the town down in the approaching season, or pull into a convenience store without the town sheriff making them promise they will not only win the state championship but win every game they play. The new coach can't do paperwork without a cadre of town businessman breaking into his office to discuss defense, or go to the supermarket without getting more of the same.

There's an ugly undercurrent of violence to all these exhortations, a promise that failure will not be tolerated. When one of the players fumbles during practice, his dad (country singer Tim McGraw, looking like Michael Madsen's baby brother), who was on the team in one of the years that it won a state championship, strides onto the field to knock his son down in disgust. When the team loses a game, the coach returns home to find local realtors have placed "For Sale" signs on his lawn.

Berg doesn't even allow us the pleasure of the game itself. Football here is just the sort of red-meat spectacle the rednecks and blowhards he's put on-screen would thrill to -- the sight of young men ground into fertilizer. When the players collide on the field, the soundtrack emits a Dolby-amplified whammy of crashing bodies and crunching bones.

The camera is shoved in the middle of the skirmishes. We see teenage boys running into outstretched arms as if they slammed into tree branches, or plucked from a midair leap by an opposing player and slammed to the ground. One kid, lying on the ground after being tackled, has his helmet kicked into his teeth.

Some of the football sequences look exciting, but they're so chopped up you see them only in flashes. And in the big championship game, with the clock running and the players trying to keep getting first downs until they score, the camera is so close in that you can't even tell what yard line they're on.

The players here are presented less as athletes than as soldiers whose sacrifices are understood to be no more than is expected of them. After one lost game, a caller to the local radio station says that maybe the kids are learning too much in school to concentrate on the game. Football may hold a future for some of these kids, like Boobie (Derek Luke), the star player being scouted by the big colleges who can barely read the USC catalog he's been sent. But for most of them, their senior season will be their one moment of glory before a life spent working at the lousy jobs their lousy education has prepared them for.

At some point in the making of "Friday Night Lights," either Berg or the studio, Universal, must have realized nobody was going to pay money to see a movie about that. So in the second half, the movie turns into a rah-rah celebration of exactly the mind-set it's spent the first half criticizing. All of the bad things that have resulted from the characters' mindless devotion to gridiron glory -- the abusive father who stays drunk to forget that the peak of his life came at 17; the barely educated Boobie's having nothing left in his life when a knee injury ends his dream of playing pro -- are converted into obstacles that test the mettle of the young warriors.

And what is it that gives them the strength to meet those challenges? Why, football, of course, and its life lessons of dedication, hard work, blah, blah, blah. It doesn't matter, finally, whether most of these kids are going to be able to put those lessons to work at anything other than menial, low-paying jobs, whether they are going to have to spend the rest of their lives in a small town where they're washed up as soon as they leave high school. It doesn't matter that there's no one to say to them, look, teamwork and persistence are great things to learn at a young age, but there are more important uses for them than a frickin' football game.

Berg tries to peddle an "it's not whether you win or lose" finale, but he can't disguise the fact that "Friday Night Lights" wallows in every piece of inspirational horseshit from every hoary sports movie you've ever seen. Thornton even has a let's-win-this-one-for-Boobie speech. ("Friday Night Lights" looks especially egregious next to the wonderful "Mr. 3000," which really does understand that sporting glory is a paltry thing next to building a decent and satisfying life you can take pride in.)

It's hypocritical, but it's not that big a loss. The movie that "Friday Night Lights" starts out being substitutes slick, cynical point-scoring for insight. "Friday Night Lights" isn't repugnant like "Very Bad Things," the first movie Berg directed, but it shares some of that movie's superior everything-is-crap smugness. It's bad enough watching Boobie get injured -- Berg has to include a shot of the opposing player who did it getting congratulated by a teammate. It's sour little details like that that leave a bad taste.

Berg doesn't show much empathy for the former high school athletes trying to live vicariously through the new crop -- he seems to think that a pop psychological explanation of their envy will suffice. Most of the team's boosters don't even get that puny consideration. The Odessa businessmen (and their wives, one of whom tells the coach not to spare a black player because "that big nigger can't be broke") are the movie's examples of boobus americanus, vulgarians in garish sports clothes who exercise the threat of their puny power to keep underlings in line. If he could, Berg would probably give them Bush buttons to wear (and seeing as the movie takes place in the fall of 1988, there's no reason he couldn't).

There's some good acting in this mess. Lucas Black manages to suggest what's roiling around inside his nearly silent character without violating the placid surface. As Boobie, Derek Luke understands that playing his character's grandstanding doesn't mean he has to grandstand as an actor. And Grover Coulson, as the uncle who raises Boobie, has some good moments: When Boobie is injured, Coulson looks helplessly back in the stands to see if the college scouts are watching, as if they could somehow have missed the moment.

Thornton gives a very fine performance here; he's one of those rare actors who is able to convincingly play decency without making it seem boring. He stays quietly in character and even manages to dry out the most potentially mawkish scenes. But the movie's determination to shy away from complexity lets him down.

The coach is well aware of the pressures on his players -- the same pressure is on him. But the movie never examines what if any complicity he feels in driving his players toward victory. It's his job, but we never know if he's tempted to tell them that there's more to life than football, or if he ever tries to make sure they don't neglect their schoolwork. When, with the best intentions, Boobie and his uncle lie to him about what the doctors have said about Boobie returning to play, you wonder why as basically decent a man as this doesn't simply pick up the phone and ask the doctors themselves.

But these are questions the movie doesn't want us to ponder too closely. The end titles tell us where the various players are now and what they are doing. There are, however, some salient facts missing. We find out that Boobie played football in junior college and now lives in Texas with his twin girls. We aren't told what he does for a living -- or if he feels confident enough to read his little girls a bedtime story.

Shares