There was a time, shortly after John Lennon's death, when "A Hard Day's Night" was almost unbearable to watch. It was bad enough that we all knew how the band's story had ended, with lawyers and negotiations and daggers of mistrust shooting four ways and then, the worst thing imaginable, silence. But in the early '80s the story took a sadder and more jagged turn. If it was hard to think of the 1980 John as dead, leaving behind some great and some mediocre solo records and a grieving widow nobody ever liked much anyway, it was incomprehensible that the 1964 John -- the one we'd loved first -- was gone too.

Movie stars die all the time; then we see their movies and they live again momentarily on the screen, and their beauty and youth are more a comfort than a reproach. But for a while there, the unrepentant exhilaration of "A Hard Day's Night" -- even if it was, perhaps, a cartoon inversion of the Beatles' real-life nightmare of celebrity -- just felt wrong. Forget all the muttered contentions that the first of the Beatles to die was the brightest one, or the funniest one, or the most beloved one. It wouldn't have mattered which one was gone. Personally, I never wanted the Beatles to reunite, but even if they were barely speaking to one another I wanted them to exist on the planet -- or at least in some alternate living universe -- as a complete set. Watching them run from screeching fans in "A Hard Day's Night," less like four individual young men than a single terrified organism, was just a painful reminder that they were permanently broken apart.

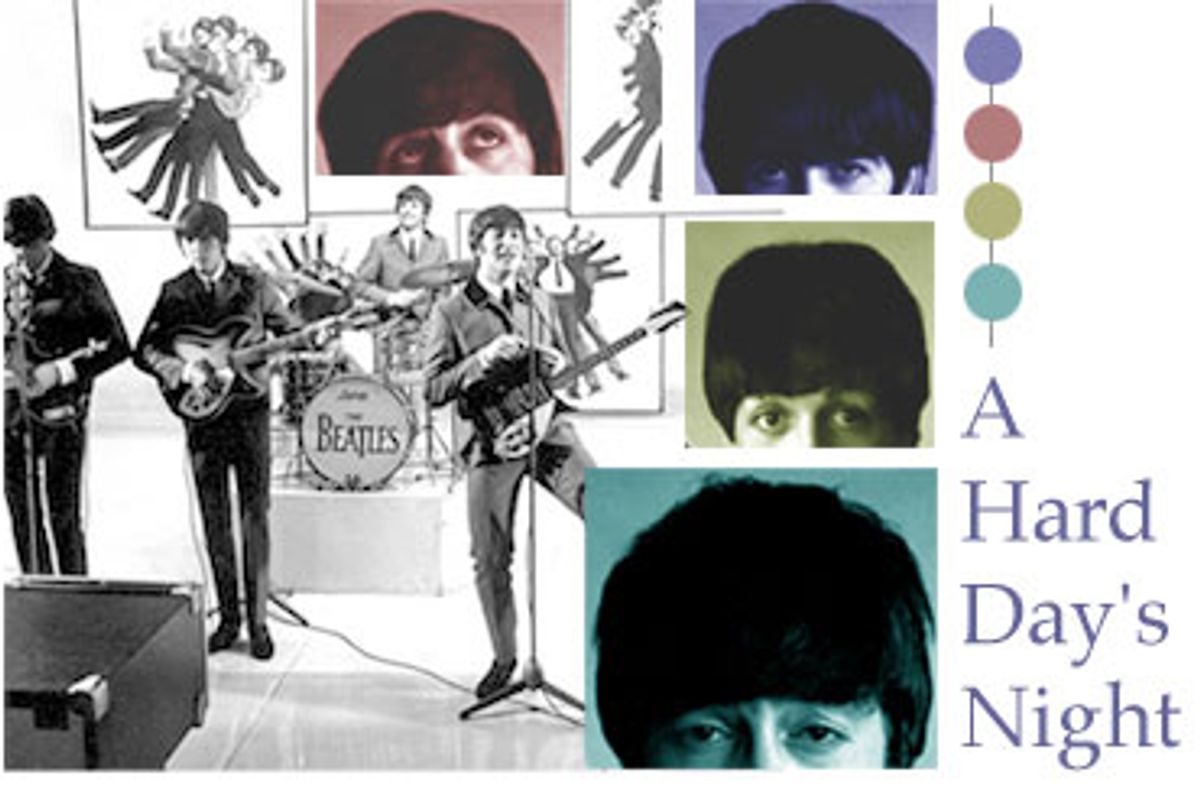

Of course, you get over these things. In rock 'n' roll, not to mention life, people you care about die, and before long "A Hard Day's Night" had returned to what it had been for me since the first time I saw it on television as a kid in the mid-'60s: an hour and a half of pure, chaotic bliss -- as if school had just let out forever. It feels good and right that as we near the 20th anniversary of Lennon's death, "A Hard Day's Night," with a restored picture and soundtrack, is beginning to make its way to theaters around the country. (It opens Friday at New York's Film Forum.) It's a celebratory act rather than a reflective one. You can go leave flowers at Strawberry Fields in Central Park if you want; I'd rather catch John taking a snort, one dainty nostril at a time, from a Coke bottle -- which, if you look closely for the joke within the joke, is actually a bottle of Pepsi.

The spruced-up "A Hard Day's Night" looks and sounds like new, although even on video it never looked like a relic. It's one of those rare pictures that are both of their time and self-renewingly modern. Director Richard Lester borrowed techniques from the French new wave (quick cutting, startling point-of-view shots) and used them to concoct a document of a joyful cultural phenomenon that's filled with joy itself.

And Gil Taylor's cinematography, crispened and cleaned up, is more of a marvel than ever. His gorgeously framed shots mark "A Hard Day's Night" as one of the most vital-looking black-and-white films ever made. When the Beatles "spontaneously" launch into "I Should Have Known Better" from the caged-in luggage compartment of a train as a group of girls cluster outside, Taylor shoots the crisscrossing fence wires not as a cold, defensive barrier but as a protective one, one that fosters a kind of intimacy: It's all that separates the Beatles from the world, but it also frames them beautifully, a visual affirmation that these four raffishly striking young men were made to be seen as well as heard.

The story line of "A Hard Day's Night" is a souped-up musical-fantasy version of the Beatles' relationship to real-life fame at the time, a fable about their having to work so hard at being the Beatles that they'd be elated just to have one day off. And so they try to take it: They've been transported by train to a city where they're scheduled to give a TV performance, but they're scuttling off and looking for mischief every chance they get.

Against the wishes of their road manager Norm (Norman Rossington), they head out to a discotheque to dance and meet girls. (Meanwhile, Paul's shifty-eyed, cantankerous grandfather, played deliciously by Wilfred Brambell, borrows a waiter's tux and heads to the casino to win some money and chat up a buxom blond or two.) The next day, Norm forbids them to leave the theater where they'll be performing until after their rehearsal is over; like disobedient schoolboys they rush out a back door, down a fire escape and onto a blissfully empty green field, where "Can't Buy Me Love" kicks in.

The whole movie is about evading capture, about longing for freedom and just a few of the perks of normal human life, but only until it's time for the Beatles to perform. Then, it seems, they miraculously find peace in the midst of the chaos of rock 'n' roll. Onstage and doing what they do best, they're happiest and perhaps most completely themselves. The thing that robs them of the chance to be average human beings is also the very thing that buys them love.

Even in 1964, at the very beginning of the Beatles' reign, it was clear how much of themselves they were giving up to their audience. Lester underscores that beautifully, both in the way he captures the intimacy of their musical performances and in the way their fans just can't get close enough to them. At the end of one of the movie's early chase sequences, you can spot George shaking a fist at the camera; it had been the first day of shooting and hordes of press and fans had showed up, contributing to the disarray of what was to have been a completely staged chase.

But Lester also goes out of his way to show the love that the Beatles' audience gave back. In the movie's final concert sequence, his camera doesn't make the euphorically hysterical girls in the audience objects of ridicule; they're simply stand-ins for all the rest of us. He shows them to us as if to say, "This is the only natural response to this sound, to these young men." As the camera scans the crowd, it rests four times on a round-faced blond, her face streaked with tears. Lester has referred to her as "the white rabbit," an obviously affectionate nickname for a girl whose charged pleasure is so close to the surface, and so genuine it's almost a compressed premonition of the devotion the Beatles would inspire for the rest of their career and beyond. She looks as if she's forgotten who she is, or what planet she's landed on: Her connection with the figures onstage is maddeningly remote and yet cosmically complete.

She wanted to know, as we still want to know: Just who were they? Watching "A Hard Day's Night" in a screening room, in the middle of an otherwise mundane workweek, I found myself enraptured not just by the look of the movie, or by the look of the boys (and God, what boys!), but by songs I'd heard hundreds of times. The suedelike harmonies on "If I Fell," the hard open chord that kicks off the title track like a clap of thunder with all the colors of the universe in it: Who were these men? I don't think I'll ever know, and that's at least half the pleasure I take in them.

I love "A Hard Day's Night" because I love to watch the Beatles move. I love the goofy sackless sack race on the field; I love the way they look onstage, restrained and almost businesslike, the way George taps his foot like a country gentleman and the way Paul jerks his head to get a sweaty forelock out of his way. I love them as individuals only because of who they were as a whole -- because how else can most of us know them? (Even a solo record is still a Beatles solo record.)

Part of the magic of "A Hard Day's Night" is the way screenwriter Alun Owen figured out how to give the right jokes to the right boy. The script may feel improvisational, but all the dialogue and action were tightly scripted. Even so, Owen made it a point to spend time with the Beatles to get a sense of the kinds of things they might say. That's why, when a journalist asks Ringo if he's a mod or a rocker, his deadpan answer ("I'm a mocker") feels like pure Richard Starkey.

The barest truth, though, is that the Beatles as individuals are closed off to most of us -- closed off to everyone except their close friends and their families. They've sometimes complained that they sacrificed themselves to celebrity, that their notoriety as one of the greatest bands in the world stripped them of any personal identity. In the new "Beatles Anthology" book, George Harrison says of the band's raging success, "It was a very one-sided love affair. The people gave their money and they gave their screams, but the Beatles gave their nervous systems, which is a much more difficult thing to give."

You might wish Harrison would be a little less churlish -- after all, the fans probably had a little something to do with financing his country estate -- but you can see his point. The fact remains, though, that we didn't just take: They gave. It's not our job to accept them as mere mortals. We have a better chance of understanding them as inseparable parts of a whole.

And partly because it incorporates visuals and music, and partly because it's simply magic, "A Hard Day's Night" gives us a priceless flash picture of that whole. It's 85 minutes of screen time that represents one crystallized moment not in the Beatles' career per se but in the parallel career they forged inside all of us, the one that will last beyond any breakup, retirement or death. As we see them in "A Hard Day's Night," the four of them together are a spectacular vision of youth and freedom, the kind of thing that ballads are written about and revolutions are fought over. Some 35 years later, they're not quite bigger than Jesus, but almost. And like him, they did give their lives for us, whether they wanted to or not.

Shares