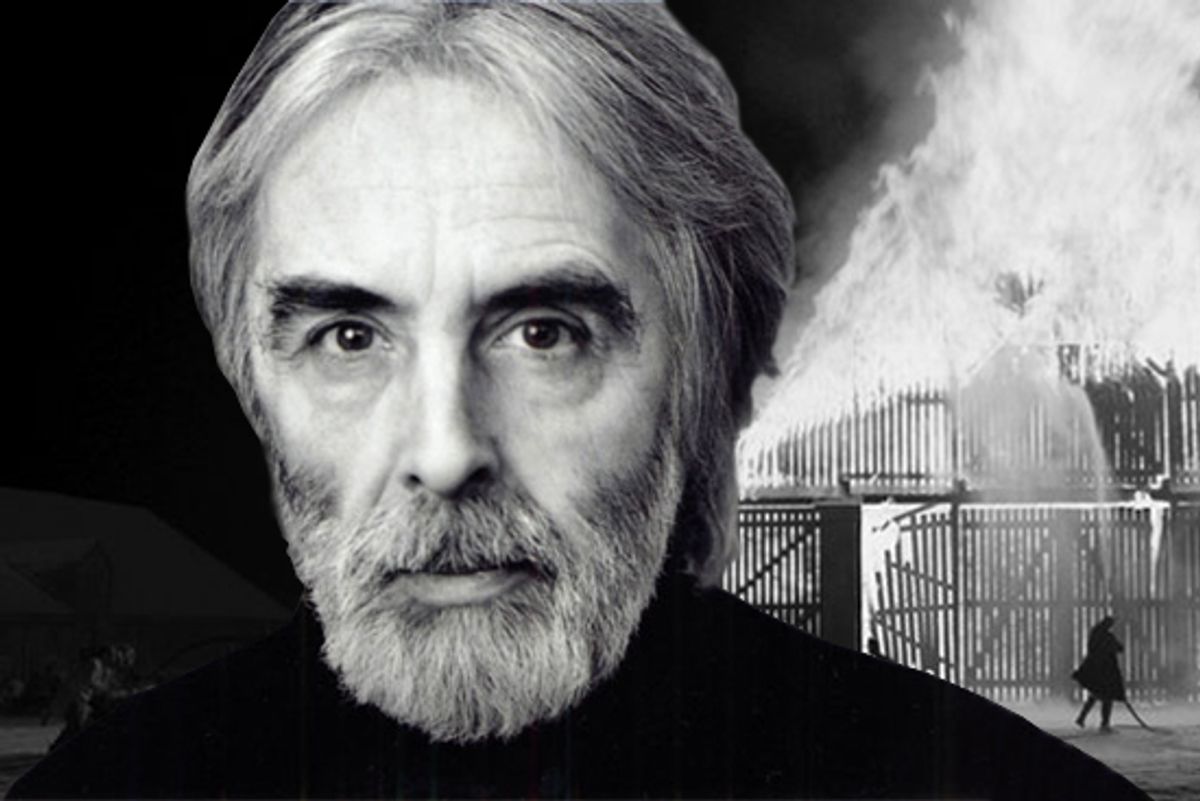

I don't know whether Michael Haneke ever plays chess or poker (the former seems a lot more likely). But either way, he'd be a deadly opponent. Mild-mannered, formal and professorial, the bearded Austrian filmmaker is not a difficult interview subject in any ordinary sense. He was neither grouchy nor combative in our half-hour conversation. He was unfailingly polite, never refused to answer a question and even cracked one or two quiet jokes.

But I gradually became aware that the director of "Caché," "The Piano Teacher" and the new international sensation "The White Ribbon" -- winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes and best-film and best-director prizes at the recent European Film Awards -- was steering our discussion exactly as he wished. Beneath his calm and courteous demeanor, Haneke exerts an inexorable, iceberg-like confidence, which you can also see in his films. With minimal effort, he brushed away my attempts to link his work to his background or his private life, and calmly insisted that the unanswered questions and unfinished narratives in his films -- the very ingredients that fascinate viewers -- are unimportant and superficial.

Now, if you've seen any of Haneke's films (others include "Time of the Wolf," "Code Unknown," "Benny's Video" and two different versions -- one in German, one in English -- of the horrifying "Funny Games") you know that they have the uniquely unsettling quality of operating on several different and perhaps contradictory levels. Haneke generally wants to draw you into a compelling story, draw a political or philosophical parable, and remind you that what you're watching is just a fiction -- "an artifact," as he puts it -- all at the same time.

In Haneke's notorious "Funny Games," a pair of amoral and sadistic killers, who are less like characters than imaginary specters, address winking asides to the audience -- and at a crucial juncture rewind the film with a remote control. "Caché," Haneke's biggest hit, appears to focus on the question of who has been making sinister videotapes of a middle-class Parisian family and leaving them on the doorstep. As in David Lynch's somewhat similar "Lost Highway," the mystery is both unsolved and (I believe) unsolvable. But Haneke isn't just trying to undermine the narrative stability of conventional cinema, although he's doing that too. He's shining a spotlight on the atmosphere of paranoia and submerged guilt in which the middle-class family's entire life has been constructed.

At first glance, "The White Ribbon" is the most mannered and most beautiful of Haneke's films, and you could describe that fact as a calculated gamble on his part. Set in a village in rural northern Germany in 1913, with World War I looming on the horizon, it's a gorgeously photographed and oddly riveting chronicle of a late-stage feudal society running on fumes. Shot in spectacular black-and-white by cinematographer Christian Berger, and marvelously acted by a first-rate German ensemble, "The White Ribbon" captures a mood of thickening tension and mounting violence as a series of brutal but apparently unrelated events -- vandalism, fires, accidents and abductions -- turn the people of the village against each other and shatter what remains of a fragile social consensus.

If Haneke's most obvious point is that the hierarchical, aristocratic society of peasant Germany was replaced by something much worse -- by the "New Order" created by its mistreated children, a generation later -- it definitely can't be reduced to a fable about the roots of fascism. "The White Ribbon" is a dense account of childhood, courtship, family and class relations in a painfully repressed and repressive society, which seems to channel both early Ingmar Bergman and the "Bad Seed"/"Children of the Corn" evil-tot tradition.

Haneke's title refers to a ribbon parents of the period affixed to the sleeves of preadolescent children suspected of "impure" thought and behavior (i.e., masturbation). On one level, this story is about a very simple notion: The physical and psychic violence inflicted on one generation by another is always passed along, often in heightened and more dramatic form. But this severe and striking period piece is also a story that subtly but constantly reminds us that it is a story, and as such cannot be trusted. Even at the risk of undermining his own film, Haneke wants us to see history as a problematic and partial narrative, one that has more to teach us about the present than the past.

I met Haneke in his Manhattan hotel suite during his visit here in September for the New York Film Festival. We sat at a round table with an interpreter between us, which only heightened the atmosphere of competition and/or negotiation. Although Haneke understands English pretty well (or at least much better than I understand German), he waited for translations in both directions. Occasionally he corrected the interpreter or broke into brief snatches of English; I've marked those passages, as they seemed like important moments in the poker game.

All your earlier films have had contemporary settings, so it's striking that you've done a period piece. I suppose there are some obvious reasons why you picked this time and place, rural Germany just before World War I. But I'd like to hear you explain it.

Unfortunately, Germany is the place and time in which ideological radicalism is most prominent, and that's why I chose to set the film there. But it would be a mistake if one were to reduce the film to a German example.

"The White Ribbon" is also your first film in black-and-white. Were your reasons for that primarily aesthetic or, I don't know, primarily philosophical?

There are two reasons for choosing to shoot in black-and-white. The first is that all of us, if we think back to that period, know it almost exclusively from photographs. Photography had been invented shortly before, and we all know the period from photographs we've seen. I thought it would be easier to enable the spectator to enter the story by shooting it in black-and-white.

That's the first reason. The other reason, however, is that shooting it in black-and-white automatically produces an element of distance for the audience, in the same way as does the use of a narrator. The film opens with the narrator saying, "I'm not sure if the story I'm about to tell you corresponds to what actually took place. I can only remember it dimly. I know a lot of the events only through hearsay." So both those elements, then, raise mistrust in the audience as to the accuracy of what they're going to be seeing, and the reality of what they're going to be seeing. Both the black-and-white and the use of a narrator lead the audience to see the film as an artifact, and not as something that claims to be an accurate depiction of reality.

Do this period and this place have any personal significance for you? You've spoken about the political importance, but you were born in 1942, the heyday of Nazism. I wonder, for example, whether your parents were young people in a similar time and place?

I think that most of my films have very little to do with me or my family. I was more interested in the theme: How are we ideologically conditioned?

All right. For film buffs, it's hard to avoid thinking of Ingmar Bergman or Carl Theodor Dreyer when you see this beautiful black-and-white photography, the rural Northern European setting, a story that's about child-rearing and young love and religion.

Of course I admire the directors you mention, but there are any number of directors I admire. I've heard the comparisons of my work, or this film at least, to Dreyer, and for that reason I recently watched "Ordet" again. I have to say that I see very little in terms of connections or similarities. In terms of the aesthetics, Dreyer's staging and lighting are very theatrical, whereas I was looking for more realistic light. If there was any specific influence, it was much more the photographs of August Sander, who was the great German photographer of that period. If we oriented ourselves to anything, it was his work.

You're depicting the 20th century here, but this doesn't look anything like the age of industrial capitalism. Was it really still the feudal era in rural Germany at that time?

At the time, 85 or 90 percent of the population lived in villages. So the vision of society that I present is a mirror of a feudal society, in which there was the baron at the top of society, going down to the farm workers. In between them, you had the teachers, the professional classes, the pastor. The film in that sense reproduces the classes that were present in society at the time. Had I chosen to locate the film in the city, then social relationships would have been far more complicated and far less easy to discern.

I suppose what you're showing us is the feudal order at exactly the moment it breaks down. I mean, the baron [played by Ulrich Tukur] is the most powerful man in the village, at least in theory. But we see his fields destroyed, and his son abducted and abused. His power is broken.

Yes, that's precisely what you see in the film.

One of the hallmarks of your style is that you withhold acts of violence from us. Horrifying things occur, in this movie and in others, but we generally don't see them. What interested me in "The White Ribbon" is that you withhold other kinds of intimate or emotional acts as well. When the farmer sits with his dead wife's body, the camera remains behind the wall. We can tell he's grieving but we literally can't see it.

I'm always trying to enable and arouse the imagination of the spectator. Especially when you're dealing with powerful emotions and tragic situations, I avoid using close-ups. First of all, the close-ups are always false. It's unrealistic. They're indiscreet and they're kitschy as well. I think it's far more powerful if you see this expression of pain indirectly. You hear a sigh, and that's far more evocative than if we'd shown a shot of him.

In this film you also express emotions that are -- how can I say this? -- not strongly associated with the work of Michael Haneke. [Laughter.] There's the relationship of the young lovers, the schoolteacher [Christian Friedel] and his girlfriend [Leonie Benesch], which is very tender and tentative. There's the heartbreaking scene in which a little boy gives his father a caged bird, and even though the father is a cruel and unsympathetic figure, we see his humanity at that moment. It's like you're throwing us a lifeline, a way out of this place: The terrible things that happen are not the only things in life.

The film depicts the story of so many people that I think it's realistic. In real life, not only catastrophes happen, but also pleasant things as well. There can be relationships that are positive. It's also economic in dramaturgical terms. If it were a film about couples and there were only two or three leading roles, then it would be different. You concentrate on the conflict, and that's more than enough to keep you busy in the film. Here I think it's important to show positive as well as negative energies. That corresponds to our experience of daily life, in which not only terrible things happen. There were love stories in concentration camps as well.

One of your principal subjects here is education and the treatment of children. Can I sum it up by saying that you think the methods of child-rearing in this time and place had disastrous consequences?

I think that education is one of the decisive points in human experience. When I was making the American version of "Funny Games," there was a word I discovered that I find is so indicative. There's a scene in which one of the two boys pees himself, and the other one says, "Please forgive him. He's not housebroken." I think that word is so illuminating: It suggests that we have to be broken for the house. We have to be broken to be acceptable socially, and that's the dilemma of every educational system.

You have to partially destroy or restrict the freedom of the individual in order for him or her to function in society. That's the dilemma of every generation, and I'm not convinced that current approaches to educational theory are necessarily the ideal solution either.

You want people to perceive this as more than a parable about the roots of Nazism, isn't that right?

The question that I'm asking is: What conditions have to be in place for people to seek to grasp such ideological responses? In a position of hopelessness, humiliation and despair, people clutch at any straw, and those straws usually take an ideological form, whether religious or political. Out of hopelessness, they turn to ideology -- the model is always the same, although the external forms may be different.

You spoke earlier about using the black-and-white photography and the narration as a distancing mechanism, a way to remind the viewer that the film is an artifact. There's another sense in which you are challenging the audience. As you did in "Caché," you lead us part of the way toward a solution of the central mystery: Who is committing these violent acts, and why? And then you seem to suggest that solving the mystery is not actually important.

Those are the least important questions. In my previous film, "Caché," the question of who sent the videotapes isn't important at all. What's important is the sense of guilt felt by the character played by Daniel Auteuil in the film. But these superficial questions are the glue that holds the spectator in place, and they allow me to raise underlying questions that they have to grapple with. It's relatively unimportant who sent the tapes, but by engaging with that the viewer must engage questions that are far less banal.

There are so many different things that take place in "The White Ribbon" that there are any number of possible explanations. It may not be that the acts have been committed by someone intentionally. For example, when the barn burns down, it's possible that was simply caused by an accidental spark. Perhaps the hay had been stored when it was too wet, and spontaneous combustion happened. Perhaps the farmer's wife who died simply fell. It was an accident, and she was not murdered. The explanations, in fact, are so unimportant. In real life, there are any number of events that take place that we don't understand. It's only in mainstream cinema that films explain everything, and claim to have answers for anything that happens. In reality, we know so little about what happens. It's far more productive for me to confront the audience with a complex reality that mirrors the contradictory nature of human experience.

It strikes me that in "Caché," and perhaps in this film as well, there literally is no answer that explains what is happening.

[In English.] There could be an answer!

Well, we can point back at you, the director of the film. Who is making those videotapes and sending them to the family? You are!

[Laughter.] Every interpretation is right.

[In German.] I always say that a film is like a ski jump. The film constructs the jump and enables the spectator to jump. It's up to each member of the audience to jump, and they're all going to jump differently. I create tension. I raise certain questions. That's my intention, but it's to give the audience a chance to respond.

[In English.] The film ends in the head of the viewer, not on the screen.

On the simplest level, you want to leave us asking: What happens next? What will the events we have seen lead to, and how do we think about them?

[In English.] Yes, and why? Why do things happen like this? Everybody has to find his own explanation.

[In German.] It's important to always try to tell a story in a way where there are several credible possible explanations. Explanations that can be totally contradictory!

I know you want this story to have present-day relevance. But you're running a risk, aren't you? Viewers can watch this beautiful, stylized film that's set almost 100 years ago in a society that no longer exists and think, "Well, that was then. Things are different now."

Yes, absolutely. It wasn't my intention simply to warm up an old subject for itself. I think the problems that existed then are the same today: Are we conditioned to accept and embrace certain ideologies? That is as relevant today as it was back then. I'm not simply trying to re-create a certain age. I'm not a history teacher.

I remember with my first film that was shown in Cannes, "The Seventh Continent" [in 1989], there was a screening and afterward we had a discussion. The first question came from a woman who stood up and asked, "Is life in Austria as awful as that?" She didn't want to accept the difficult questions being raised in the film, so she tried to limit them to a specific place and say, "That's not my problem." You could make the same mistake with this film, if you see it as only being about a specific period.

"The White Ribbon" is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, with wider national release to follow.

Shares