To say that Ron Galella provokes strong reactions is putting it too mildly. Significant chunks of Leon Gast's highly entertaining and skillful documentary "Smash His Camera" consist of lawyers or journalists or Galella's fellow photographers sitting around and arguing about whether the rumpled "paparazzo superstar" of the 1970s (his term) is bottom-feeding scum or a legitimate servant of the public interest or, God help us, even an artist.

Former Metropolitan Museum director Thomas Hoving, who developed a late-life avocation for appearing in documentaries to piss all over people, speaks of Galella with acid contempt, asking what we want alien archaeologists to find in 10,000 years: Galella's shots of Jackie Onassis and Marlon Brando, or the paintings of Titian and Leonardo? Let's answer his question with another question: Do we want them to understand our civilization as it really was, or as we wish it had been? Because Galella's daring and demented pursuit of famous people, especially the ones who really, really didn't want their picture taken, is a telling chronicle of our age.

Even firebrand civil-liberties lawyer Floyd Abrams, who has never hesitated to defend smut peddlers and white supremacists threatened with government censorship, refers to Galella as "the price tag on the First Amendment" -- that is, as a repellent example of how far we must go to protect freedom of the press. Abrams is clearly correct that Galella's decades-long stalking of Jackie O., in particular, crossed all possible boundaries of decency, taste, decorum and common sense, without breaking the law in any specific instance. Onassis took him to court twice and won restraining orders both times, and Galella was often reviled as a sleazebag invading the privacy of America's beloved First Widow. (But he never had any trouble selling his pictures.)

Younger readers have likely never heard of Galella, although he played an instrumental role in creating the lightning-speed, invasive celebrity-media complex that so dominates our nation's dubious public life. Indeed, as a painful coda to Gast's film demonstrates, some younger people haven't even heard of his subjects. (We witness a youthful assistant at Galella's New York gallery show staring blankly at photos of John Belushi, Grace Kelly and Henry Kissinger, unable to identify any of them. Reading the legend on the back of a shot of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, she says, "That's, uh, Tyler Burton.")

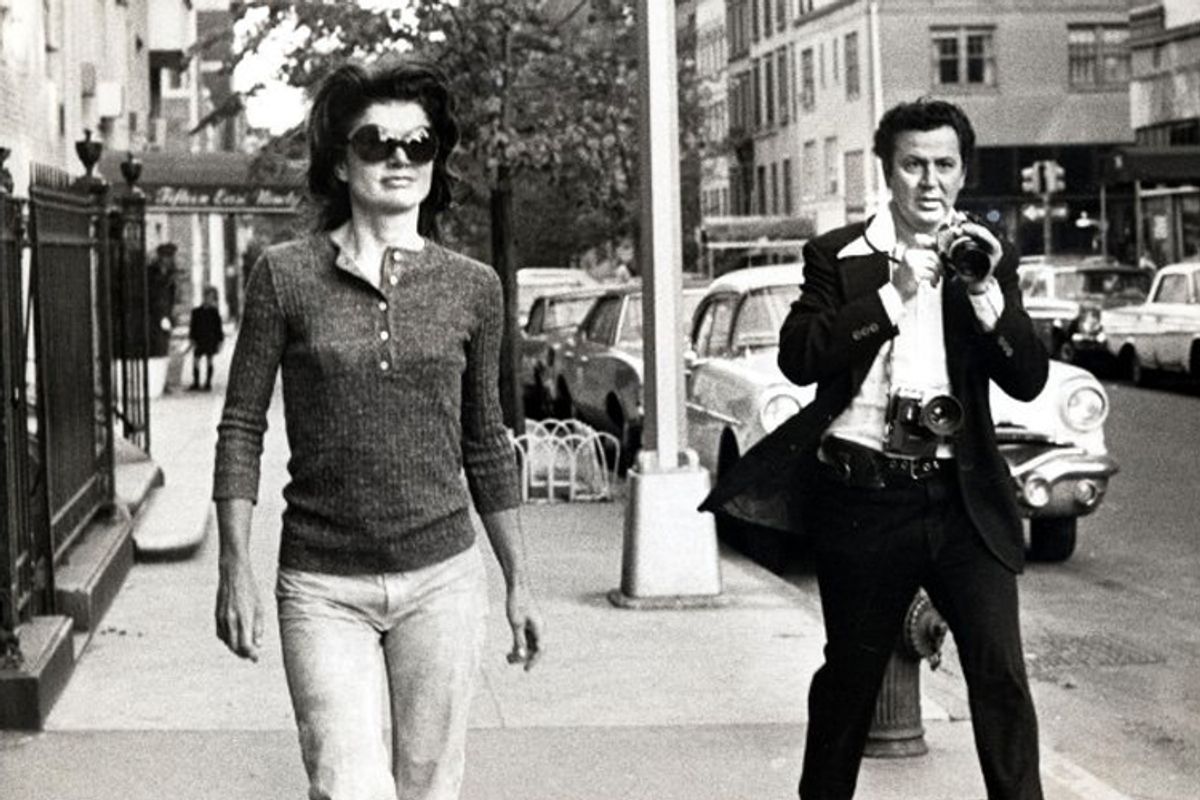

Although the term "paparazzi" and the species it describes both emerged from European pop culture -- and specifically from Fellini's 1960 film "La Dolce Vita" -- Galella became the most notorious and relentless American specimen. On one famous occasion, he hid in the bushes in Central Park to capture Onassis and her son, John F. Kennedy Jr., then aged about 8, as they returned from a bicycle ride. Onassis, who almost never spoke to Galella despite their years of proximity, told a Secret Service agent: "Do you see that man? Smash his camera!" (Galella got the camera into the trunk of his car before that could happen.) He concealed himself behind a coat rack in a Chinese restaurant to catch her at dinner, bought tickets to plays she was attending, and once wangled his way into the Christmas pageant at John Jr.'s private school.

A few years later, one night in the early '70s, Marlon Brando punched out Galella on the street in lower Manhattan, knocking out five of his teeth and breaking his jaw. Brando wound up settling the ensuing lawsuit for $40,000, which very likely struck him as money well spent. Although Galella comes off in the film as a peculiar, obsessive man with little self-understanding, you can't say he lacks a sense of humor; he showed up for Brando's subsequent public appearances wearing a football helmet.

A wily, garrulous wisecracker who lives in a suburban New Jersey house Carmella Soprano would shun as overly vulgar -- the "Italian garden" composed of artificial plants! The rabbit cemetery! -- Galella is extensively interviewed in the film, discussing his various methods and subterfuges but never talking much about his motivations. He's still working in his late 70s, chasing Brangelina around at movie premieres, along with several dozen of his progeny. We witness a telling exchange between him and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the nephew of his most famous target, who cracks, "You're too old now to hide in the bushes!"

If the legal issues raised by Galella and his ilk remain murky -- must "public figures" abandon every expectation of privacy whenever they leave home? -- so too do the philosophical and, I guess, epistemological quandaries surrounding the relationship between celebrities, the media and the public. Galella's friends, including gossip columnist Liz Smith and former Life photo editor Peter Howe, paint him as a lovable guy who meant no one harm, and suggest that even his antagonistic relationship with Jackie Onassis was a two-way street that burnished both their images -- hers as aloof and unattainable feminine perfection, his as the unsinkable shutterbug who could penetrate even the Ice Princess' palace of privacy.

Working at film festivals, I'm often around Galella's descendants -- the British and Italian paparazzi at Cannes are an especially ferocious breed -- and they're generally hardworking, hard-partying pros who serve the valuable function of reminding people like me what the whole enterprise is really about. Even the most pseudo-intellectual of us is there, in part, to bask in the reflected glamour of the stars. If we want to dress that up in fancy adjectives, that's great; Ron Galella and the legions who followed him just try to capture it in the raw.

With gallery shows and this movie and pictures in the Museum of Modern Art, Galella has now become respectable, or at least historical; somewhere Thomas Hoving's shade is still spitting invective. (Hoving died last December.) Years ago Andy Warhol described Galella as his favorite photographer, and in an age when the work of art has largely become separated from craftsmanship -- it can be an act, a concept or a process -- the question of whether Galella is an artist answers itself. His whole career is an insidious and destructive work of art -- maybe not "termite art," in Manny Farber's oft-misunderstood phrase, but more like earwig art.

By his own admission, when it came to Jackie Onassis, Galella was also the creepy, obsessive kind who channeled his fixations into his work. Why follow around a woman who studiously ignored him, year after year? "I've analyzed that," he says. For most of those years, he wasn't married and had no girlfriend. "So it was like Jackie was my girlfriend."

"Smash His Camera" is now playing at Cinema Village in New York, with wider theatrical release, HBO broadcast and DVD release to follow.

Shares