I don't imagine this offers much comfort to the Japanese people right now, but no culture in the world has been so shaped by disaster, or so obsessed with it. It is beyond words like "irony" or "coincidence" to express the fact that the only nation ever to suffer the effects of nuclear war now faces a nuclear catastrophe of unknown scope and unforeseeable consequences, following one of the biggest earthquakes in history and the resulting tsunami. Furthermore, I recognize that it borders on profanity to start talking about movies after thousands of people have died, and many thousands more face a dangerous and unstable situation. Culture cannot "heal" those kinds of wounds, and cannot make the dead live again. But it represents the collective means for the survivors, over time, to come to terms with what happened. One can argue that Japanese pop culture, in the years since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has become an extended course in post-traumatic psychology and disaster preparedness.

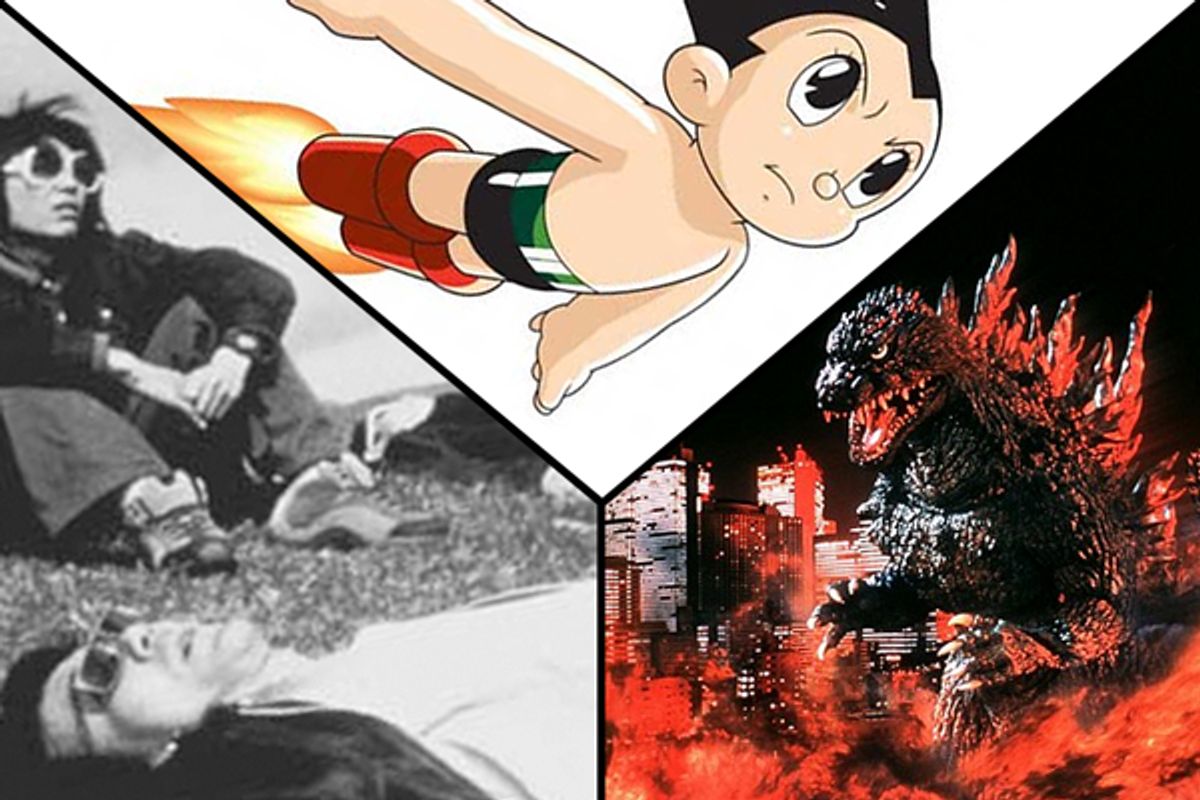

Sometimes the connection is obvious, as in the first "Godzilla" film of the mid-1950s, whose undisguised anger at nuclear-armed Yankee imperialism had to be concealed in a bastardized, American-friendly version. But it's striking that so many areas of Japanese pop culture that have nothing to do, at least officially, with World War II or the Bomb, are so concerned with violence, war, disaster and nightmarish transformation, from yakuza films to apocalyptic science fiction and gruesome horror flicks. All that becomes even stranger when you consider that postwar Japan may well be the least violent society in human history: While 21st-century America has averaged five or six murders a year per 100,000 population (which is fairly low by our standards), Japan averages much less than one murder per 100,000, with other violent crimes also barely registering.

It's unfair to suggest that all the weirdness in Japanese pop culture derives from Hiroshima, an event that only a relative handful of older people can now remember and a large proportion of younger people are undoubtedly sick of hearing about. (The inherent fragility of living on an archipelago that's frequently subject to large earthquakes and devastating tidal waves has a lot to do with it, too.) But the legacy of disaster -- informed largely but not exclusively by the A-bomb -- has had ripple effects throughout Japanese art and culture in ways too myriad to explore here. Indeed, once you start looking for disaster trauma in Japanese films you can find it almost everywhere; the nine movies and one TV series I've mentioned here are only meant to suggest the breadth of the phenomenon.

Clint Eastwood's maudlin and mediocre tsunami movie "Hereafter" was just pulled from Japanese distribution, and one can understand why nobody there wants to watch that right now. But it's not because that island nation's famously stoical people are afraid to face the reality of death and destruction. This is not a silver lining, because there is no silver lining to Japan's situation right now, but I feel confident of this: Japanese filmmakers, heirs to one of the world's greatest cinematic traditions, will tell us this story in their own way. They've been preparing for this for a long time.

The plucky little robot warrior who pioneered the anime genre (and the manga, or Japanese comic book, genre before that) represents one side of Japan's confrontation with nuclear disaster: An attempt to accentuate the positive. (See also Gamera, the nuked-out chelonian defender of children.) But there's also a tragic back story to Astro Boy's adventures, since the scientist who invented him originally meant him as a replacement for his dead son, one who turns out to be incapable of human feeling. (Any resemblance to the Pinocchio legend, and to the Kubrick-via-Spielberg film "A.I.," is probably no accident.) As any anime fan already knows, Astro Boy's Japanese name translates as "Mighty Atom."

Godzilla, Gamera, Mothra and their friends

Every article ever written about Godzilla cites the big lizard as a nuclear fable or allegory, especially in his original mid-'50s incarnation, when he was at his angriest and most destructive. But until I read Oxford professor Peter Wynn Kirby's recent online New York Times post, I hadn't realized that the original 1954 "Gojira" (often packaged as such to differentiate it from the later, American-friendly version with Raymond Burr) was a response to a specific disaster -- not the Hiroshima bombings but the poisoning of a Japanese trawler crew by an American thermonuclear device tested near Bikini Atoll. It's fair to suggest that the later Japanese movie monsters of the '60s and '70s put a vastly friendlier spin on nuclear power, and even the Big G ultimately becomes a misunderstood, almost tragic, kid-friendly figure, bearing a suspicious resemblance to a battered Siamese tomcat.

Grave of the Fireflies and Barefoot Gen

Japanese postwar culture devoted tremendous energy to forgetting about what had happened in August 1945, but you know what they say about the return of the repressed. Anime was pretty well established by the '80s, and wasn't entirely for kids, but the genre got a violent jolt with the unforgettable wartime fables "Grave of the Fireflies" (1983) and "Barefoot Gen" (1988), among the first efforts in Japanese pop culture to depict the firebombing of Tokyo and other major cities (in the first film) and the history-shaking Hiroshima nuke (in the second). Those films spoke to and for a postwar generation that couldn't personally remember the events in question, and their effects have been far-reaching.

Katsuhiro Otomo's now-legendary anime film (based on his own manga) appeared the same year as "Barefoot Gen," and has nothing specifically to do with Hiroshima or the A-bomb. But its slick and sinister vision of a dystopian city of the future called Neo-Tokyo, dominated by secret government projects, vain and corrupt scientists and underground biker gangs, drew as much on the apocalyptic collective unconscious of Japan as it did on "Blade Runner." Along the way, Otomo established a kind of cultural template -- in which today's orderly Japan will be replaced by the nightmarish chaos of the future -- that's been a running theme of manga and anime ever since.

Shinya Tsukamoto's low-budget 1989 cult classic pretty much introduced cyberpunk to Japan, long before the general public had ever heard the word, but this David Lynch-influenced nightmare about a man who turns into a machine also embodies the distinctive pathologies of post-Hiroshima Japanese pop culture. Tsukamoto might be outraged by the suggestion that his movie is the result of some post-nuclear hangover, but to me the formal disorientation and technological-psychological terror of "Tetsuo" speak for a generation marked by a national trauma. Like "Akira," this movie launched a zillion imitators (including Tsukamoto's various wacked-out sequels), establishing the techno-Kafka nightmare transformation as one of recent Japanese pop's favorite themes.

Aficionados can argue about whether Hayao Miyazaki is indeed the greatest exponent of Japan's anime tradition (my vote: yes) or whether this dark and spectacular environmental fable is his best film (yes again). You can't reduce "Princess Mononoke" to a post-Hiroshima allegory, and I'm not trying to. This 1997 film weaves Japanese fairy tale and myth, the influence of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, and a highly contemporary eco-consciousness into a work with all the complexity and texture of a masterpiece. "Princess Mononoke" isn't about the A-bomb any more than "The Lord of the Rings" is about World War I, and maybe a bit less than that. But it's a distinctively Japanese work of art, imbued with the sense of human arrogance and folly, and the sense that the precarious balance of ordinary life is always poised on the brink of destruction.

Shinji Aoyama's black-and-white, minimalist near-masterpiece from 2000 runs almost four hours and has been described by the director as a remake of John Ford's "The Searchers" inspired by the Sonic Youth album "Daydream Nation." It begins with a bus kidnapping -- which we see only as a few fragmented images -- but that episode of violence is over almost as soon as it begins, and the rest of the film is concerned with its survivors. "Eureka" has been highly influential in formal terms, inspiring a new generation of lo-fi, naturalistic filmmakers around the world. But beyond that, it's difficult for non-Japanese viewers to avoid seeing it as a partly conscious allegory -- diagnosis might be a better word -- about a nation haunted by its traumatic past and paralyzed by dread of the future.

Arguably the greatest film of the so-called J-horror wave of the late '90s and early 2000s, Kiyoshi Kurosawa's "Pulse" brought the current of apocalyptic dread that runs through Japanese pop culture into the Internet age with a vengeance. Part mournful art film, part techno-paranoia and part creeped-out ghost thriller, "Pulse" is an imperfect but memorably haunting experience, which recalls the nuclear disaster (and suggests the original "Godzilla" film) while spinning a contemporary film about a soul-sucking website that makes people disappear.

I guess Yoshihiro Nakamura's crackpot, "Donnie Darko"-style fable about how a forgotten mid-'70s punk single saves the earth from destruction in this century was just too weird and specific and Japanese to reach an American audience. (As far as I know, "Fish Story" was never released in this country, and isn't available on Region 1 DVD.) For me, at least, it's one of the seminal works of Japan's post-post-Hiroshima cultural moment and one of the most enjoyable unknown films of recent years. Oddly but perfectly balanced between pitch-perfect period farce, romantic tragedy and sci-fi mock-apocalypse, "Fish Story" is fueled by the faith that stupid and pointless dreams are worth pursuing and that Japan's perverse culture will outlast all destructive forces. I only wish that cheesy but wonderful punk single, with the mysterious mid-song silence that spawned so many terrible rumors, could do something to help the Japanese people right now.

Shares