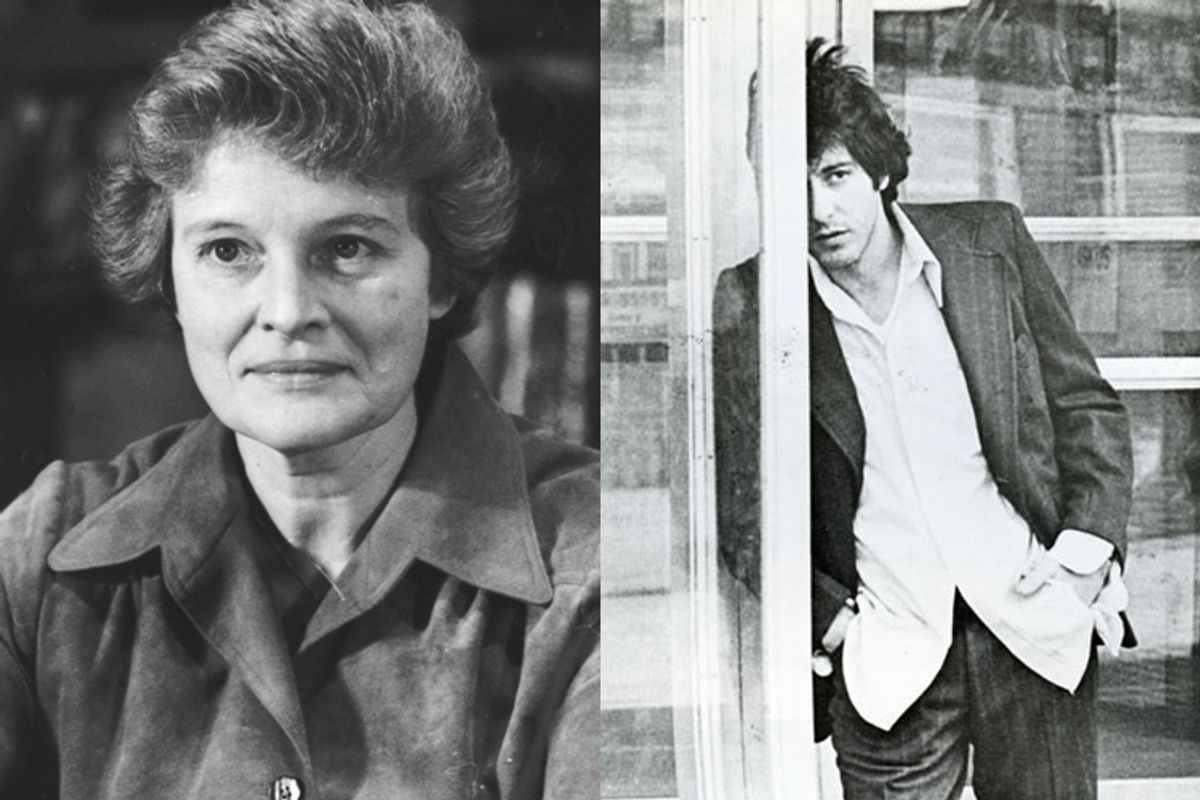

Dede Allen, who died Saturday at age 86, is being described as an accomplished film editor, and she certainly was that. She was best known as the Oscar-nominated editor of Arthur Penn's "Bonnie and Clyde" (1967), a film that deftly navigates many different modes (gangster film, satire, psychosexual drama, cornpone comedy) and deploys adventurous cuts and slow motion to transform violence from an event into a statement. Allen also edited other notable films, including "The Hustler," "Rachel, Rachel," "Serpico," "Dog Day Afternoon," "Night Moves," "Slap Shot," "Reds," "The Breakfast Club" and "Henry and June." And she was the head of postproduction at Warner Bros. for eight years in the 1990s.

But that abbreviated résumé doesn't begin to capture the soul of her work. Like a great actor or composer, Allen could adapt her talent to suit a given subject without stifling her personality or her aesthetic.

She could build an action scene with the best of them: think of the "Attica!" sequence in "Dog Day," or the whistle-blowing cop hero of "Serpico" disarming a hostile fellow officer; or the slow-building train station sequence from "Reds," Louise scanning every passenger car and knot of bodies for a glimpse of her lover John Reed, her hopes sinking with each successive reaction shot. She had fearsome technical chops. The aborted police raid on the bank in "Dog Day" is a blizzard of quick cuts covering action inside and outside the building, some of which appear on-screen for a second or less.

But she was more often described as a "performance editor." That's high praise. It takes special intuition to cull raw footage of actors' performances and piece the best stuff together to create compelling, memorable characters -- ones you can imagine having lives beyond the edges of the screen. Allen had that intuition, that gift.

Her best work has a people watcher's sensibility: a rapt yet affectionate eye. Think of Communist revolutionary John Reed on his deathbed in "Reds," asking Louise Bryant to come to New York with him ("I've got a taxi waiting"), his voice buoyant, his eyes frightened; or private eye Harry Moseby in "Night Moves" confronting his wife and her boyfriend at home, but pausing beforehand to lounge on her couch, survey the lover's feast arrayed on the coffee table and help himself to a glass of wine; or Fast Eddie Felson in "The Hustler," going on a picnic with his girlfriend Sarah Packard and expounding on how "anything can be great"; or the assistant principal in "The Breakfast Club" interrogating the detention kids, hoping to learn which of them removed a screw from the library door.

"Breakfast Club" writer-director John Hughes said he hired Allen based on "Dog Day," a suspenseful film that's almost all talk. Consider the above-linked scene from Hughes' teen flick and you can see the logic in his decision. Its spine is the animosity between the blustering principal and chief troublemaker John Bender, a wiseass who removed a screw from the library's front door. But rather than fixate on this conflict and push the other characters to the margins, the scene keeps cutting to the other teens' reactions as they take stock of themselves (and their detention-mates) and briefly decide to set aside social differences and join forces against The Man.

Watch what happens at the 1:50 mark, when Molly Ringwald's suburban princess, Claire Standish, sticks up for Bender. Bender glances at Claire with surprise and appreciation; she responds with a reflexive semi-sneer that confirms her superior position in the school's social hierarchy. It's a moment of near-connection foreshadowing the real connection ahead. The scene conveys all this information and more in a couple of terse close-ups.

Any appreciation of Allen is likely to start with "Bonnie and Clyde," then assert that Allen's work on that film helped bring French New Wave techniques into the American mainstream -- and how the lovers' death spasms launched a new mode of filmmaking built around balletic violence. That film and its finale are important, no doubt. But for my money the highlight of Allen's career -- and the sequence that best illustrates her uniqueness -- is the opening of "Dog Day Afternoon."

Scored to Elton John's "Amoreena," the only piece of music in an otherwise score-free film, it's a tribute to Brooklyn and to the urban experience in general. It's also a burst of tough lyricism that's more characteristic of Allen than of "Dog Day" director Sidney Lumet, a director not known for poetry. It can (and thanks to YouTube, does) work as a time capsule and as a self-contained work of art that can be watched and savored again and again. Yet there's nothing indulgent about it. Think about the plot of "Dog Day" and you realize how efficiently Allen's montage sketches the movie's setting and themes, and how elegantly it foretells the hero's doom.

From John's first line ("Lately I've been thinking how much I miss my lady") the sequence conjures an aching nostalgia, not just for the hardscrabble Big Apple of 1975 that Allen's montage preserves (in a kind of miniature stealth documentary), but for the hero's life as a free man -- a world that existed before his crime landed him in jail and deprived him of every experience, emotion and relationship that meant anything to him. The delayed introduction of Sonny and his partners waiting outside the bank is preceded by two shots of the Calvary cemetery in Queens (the Manhattan skyline looming behind a field of tombstones), then a shot of a Kent cigarettes billboard noting the current time of day -- the exact minute when Sonny's freedom ended.

The opening of "Dog Day" is about what Sonny lost, and the rest of the film is about how he lost it. This sequence is about the necessity of recognizing and appreciating the beauty of life itself. A better tribute to Dede Allen's artistry is hard to imagine.

Shares